Bringing the writer, psychiatrist, and revolutionary Frantz Fanon’s world-shaking work to the screen with all its incisive nuance, beauty, and violence intact is no mean feat. Issac Julien’s Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask (1995) takes on the task to great effect. The film employs a variety of visual and discursive modes—documentary, essay, poetic imagery—to not only convey Fanon’s life and ideas, but also the feelings that his post-colonial theories continue to stir among freedom-seeking people today.

In Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask, Julien creates an atemporal space wherein, much like psychoanalysis, past and present unite. To do so, he includes Fanon’s own writing alongside critical insights from scholars and blends them with tableaux, lo-fi videos, projections, and dramatic lighting, to create a cinematic rendition of Fanon’s unique approach to theory, which often brought together different disciplines—psychoanalysis, journalism, philosophy— in its multi-pronged criticism of colonial thought. The film moves from Fanon’s early life in Martinique, which is depicted with cinematic still lifes and Caribbean music, to his time in Paris, where the consciousness-altering event at the heart of Fanon’s 1951 book, Black Skin, White Mask, occurs.

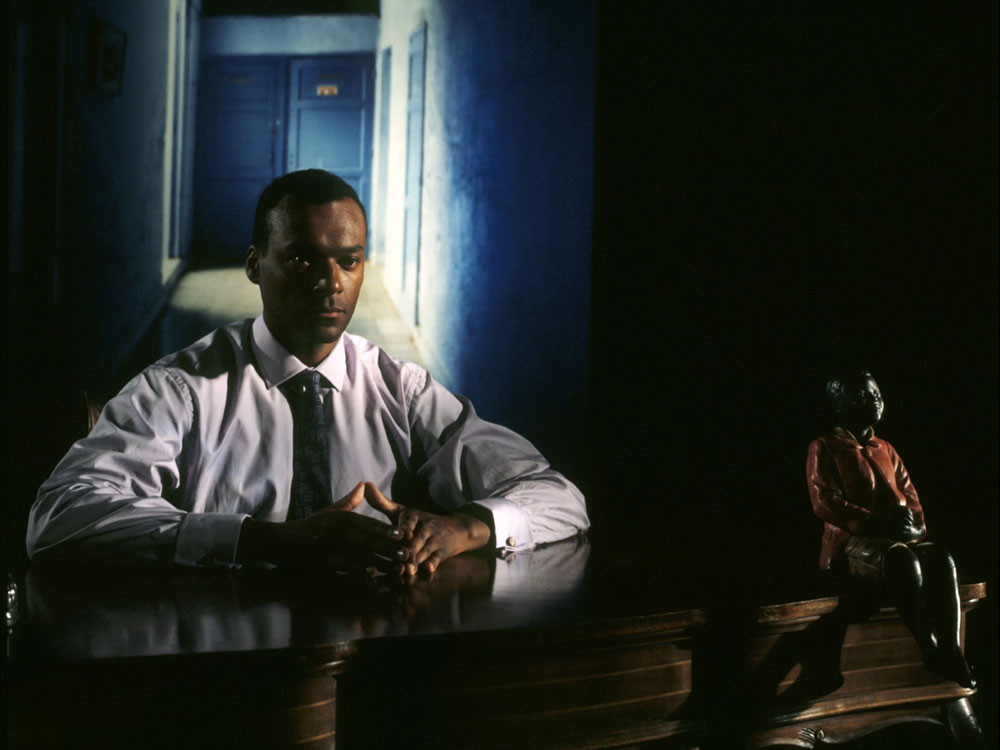

Julien takes great care to explicate the psychological shift at the heart of Fanon’s work. The young psychiatry student earns a profound but painful insight into racism and its accompanying othering when he witnesses himself being seen by a white child in France. “Look mommy, a negro,” he hears the kid say. Experiencing the child’s gaze, that of the other, his self becomes shattered. This other’s gaze forces Fanon to see himself as something frightening, an idea foreign to his previous psychological identity. With this new fissure, the naturalized structures of society and identity fall away for Fanon, leaving the racialized subject and the gaze of the other in their place. This complex idea is given both intellectual clarity and aching pathos in Julien’s film, in large part thanks to Colin Salmon’s magnetic portrayal of Fanon.

The film shifts from Paris to Fanon’s time in Algeria, where his stated purpose was “to work in a country under colonial domination.” Julien depicts the move with a theatrical flair by showing Fanon set off on foot into the desert carrying suitcases. The implication is that he has now left the beaten path of the bourgeois intellectual mainstream. After all, it was in Algeria where Fanon’s thought would become more radical, finding there the real resistance to violent colonial oppression he was unconsciously seeking. Using more arresting imagery, including excerpts from Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers (1966), the film brings life to the fiery ideas Fanon developed during his time with Algeria’s National Liberation Front. His experiences in Algeria led him to write The Wretched of the Earth, which the Jamaican-British sociologist Stuart Hall calls ”the bible of the decolonization moment” in the film.

Throughout the film, Julien also includes dissenting views on Fanon’s work but these only strengthen the daring power of his film. In light of current struggles for freedom, particularly that of Palestinians who are currently fighting a US-backed genocide being carried out by the Israeli state, it seems impossible to diminish the still exhilarating and liberating impact of Fanon’s work. Julien’s enlightening Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask is a tribute to the many dimensions of Fanon’s work, as well as the spirit of the man himself, who, as the film concludes, makes one final prayer: “Oh my body, make of me always a man who questions.”

Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask screens tonight, February 12, at Maysles Documentary Center as part of the series “Made in Harlem — The Lafargue Clinic Remixed.” This screening will be followed by a panel discussion between author Gabriel N. Mendes, Dr. Anna Ortega Williams, and organizer Desiree Joy Frias.