In 1992, Ron Vawter first performed his one-man show Roy Cohn/Jack Smith, a diptych portrait of “two very different white male homosexuals,” each of whom died of AIDS in the mid- to late-1980s. Cohn, mentee to Joseph McCarthy and mentor to Donald Trump, went to his grave denying his HIV diagnosis and expressing no remorse for a life spent hectoring communists and gays as a means to political power. Smith lived openly and furiously. He created the American cinematic underground of the 1960s alongside Ken Jacobs and Jonas Mekas, and faced obscenity charges for screening Flaming Creatures (1963), his orgiastic, ultra-low budget pageant of queer flesh and camp glamour. In the stage show, Vawter first inhabited Cohn and then Smith, the former in a comically massive bow-tie preparing to speak to the American Society for the Protection of the Family and the latter in clattering orientalist jewelry delivering his 1971 monologue “What’s Underground About Marshmallows.” Forcing the two to share a stage posthumously was, in Vawter’s words, an attempt to “balance one against the other for my own theatrical motives.”

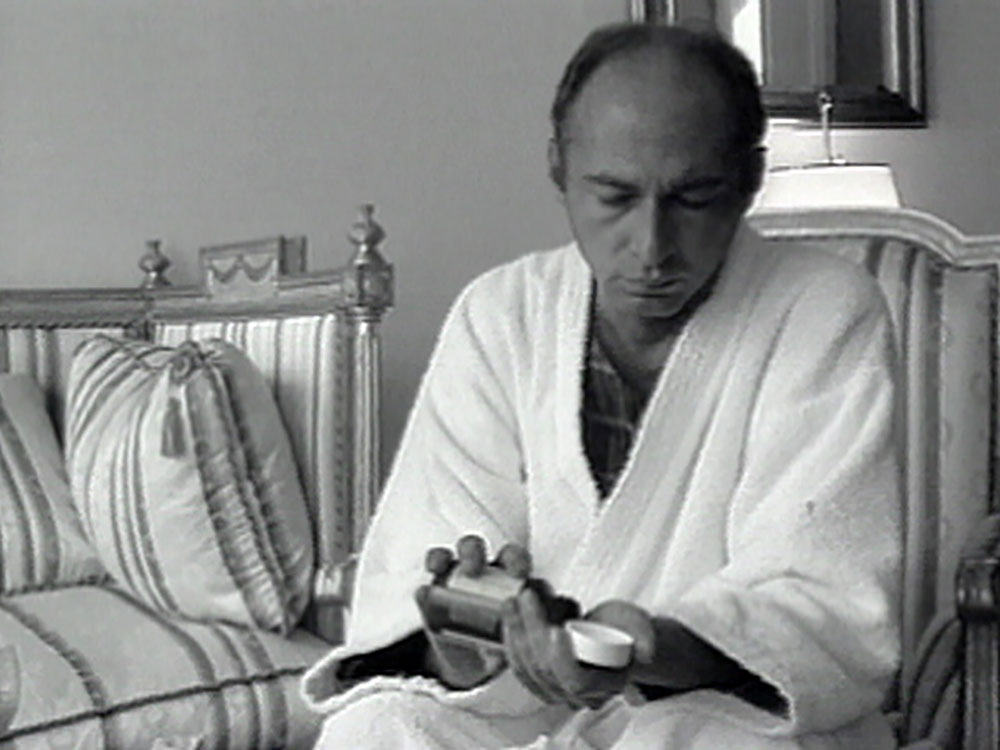

Shortly before Vawter’s own AIDS-related death in 1994, filmmakers Gea Kalthegener and Douglas Ferguson shot Free Fall, a portrait of Vawter as he prepared to perform Roy Cohn/Jack Smith in Amsterdam. In hazy black-and-white video, they capture Vawter’s almost unbearable gravitas and occasional bursts of humor as he contemplates the end of his life and mourns the future persecution of people with AIDS. Blessed with the stately voice of a news anchor and the aquiline profile of a Roman emperor, Vawter is mesmerizing whether he’s smoking a cigarette in the bath or replicating Smith’s goatee with greasepaint backstage. He profoundly claims that the audience’s awareness of his declining health contributes to the show’s spectacle of an actor moving “beyond the body” and tapping into a universal desire to transcend illness in pursuit of beauty.

In Cohn and Smith, Vawter saw “the consequences of society repressing the sexuality of some of its members.” He makes no plea for empathy toward Cohn, who unquestionably left the world in worse shape than he found it, though just how much worse Vawter wouldn’t live long enough to discover. He’s clearly as enthralled with Smith’s camp shamanism as he is disgusted by Cohn’s wretchedness, but the two subjects are nevertheless joined by their shared end and the centrifugal force of homophobia that pushed them to the margins. Both men had a steeliness of character that secured for them a place proximate to the mainstream of American life. Cohn architected the pugilistic shamelessness that now threatens to capsize American democracy and the world eventually caught up with Smith’s glitter-choked genderfuckery. Even as deaths from AIDS have plummeted in the West in the 21st century, the repression that caught Vawter’s fascination continues burrowing around in search of hospitable political climates.

Free Fall screens tonight, April 29, at Anthology Film Archives as part of “Ron Vawter’s Roy Cohn/Jack Smith.”