For a few years in the 1950s, Spencer Williams was one of the most famous Black actors in America. It was a mixed blessing: he reached the pinnacle of his success playing Andy on TV’s notorious Amos & Andy. By the end of the show’s controversial run in 1955, Williams found himself part of a generation of Black comedians – Mantan Moreland, Lincoln “Stepin Fetchit” Perry, Willie “Sleep n’ Eat” Best – largely consigned to the dustbin of history.

Less widely known was that Williams was second only to Oscar Micheaux as the most prolific African American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century. From 1931 to 1949 he directed ten features and three shorts in a range of genres – comedies, melodramas, musicals, a war film, and a music documentary. Williams’s films were among the several hundred “race movies” that played in a network of Black screening venues from Dallas to Harlem from the silent era to around 1950. While Micheaux’s tough, incendiary work has kept him a central figure in Black film history, Williams’s eccentric oeuvre has mostly remained outside the canon (with the arguable exception of his popular sin-n-salvation drama The Blood of Jesus [ed. note: as featured by Stream Slate on Easter], which became the first “race film” selected for preservation by the National Film Registry).

Race movies have become more widely seen and studied thanks to the release of Kino’s Pioneers of African American Cinema project in 2015 and its subsequent distribution on streaming platforms. Before that, one of the best places to find a wide assortment of “All Black Cast Classics” was from Something Weird Video, those tireless rescuers of all forms of cinematic detritus. Now, like a bizarro-world version of Kino’s meticulous restorations, Something Weird’s original S-VHS master of Williams’ Go Down, Death! (1944) has been lovingly digitized by the American Genre Film Archive, available on a pay-what-you-can basis with proceeds donated to the Movement for Black Lives. “To this day, some of these mega-rare tapes include the best-available versions of movies that have fallen into the black hole of neglect,” notes AGFA’s press release. Seeing Williams in these less-than-state-of-the-art conditions is a reminder that as recently as a few years ago, he and the entire movement he represented still felt a little bit disreputable.

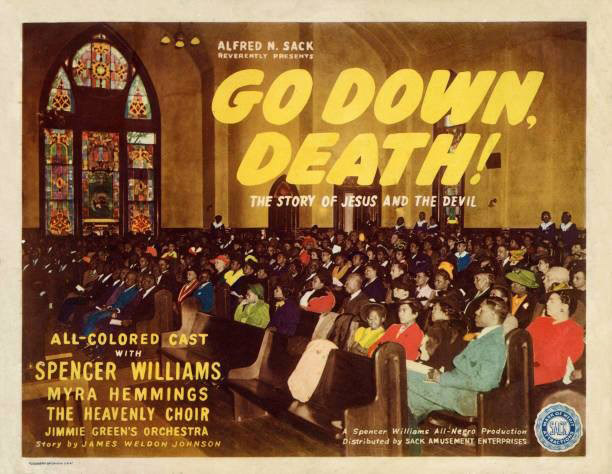

In Go Down, Death!, the burly Williams stars as an unscrupulous juke-joint owner who laments that the local church is siphoning his Sunday business. He devises a scheme to discredit the kindly preacher by photographing him in a compromising position with three ladies of easy virtue. The deed done, he ends up in a tussle with his adoptive mother over the negatives, accidentally killing her in the process. Haunted by guilt, he imagines himself on his knees at the gates of Hell – depicted via stolen footage from L’Inferno (1911). Seeing the spectacular, dreamlike imagery of the silent epic juxtaposed with Williams’ more prosaic footage is a head-spinning experience.

By the ‘40s, the dwindling number of race movies were largely financed by Alfred N. Sack, a white-Jewish entrepreneur who owned a string of southern theaters – and the only person regularly financing Black filmmakers. Sack held the pursestrings, but Go Down, Death! still feels like local, community effort – heavily influenced by Hollywood melodramas, but unbeholden to any rules of film grammar. In the same year as To Have and Have Not, Meet Me in St. Louis, and Going My Way, Williams’ camera captured the Black houses, churches, and nightclubs of Dallas, and many of their non-actor denizens – proof that the history of cinema is vast, contains multitudes, and extends far beyond the borders of Los Angeles.

Go Down, Death! is available to stream from the American Genre Film Archive.