The 1960s saw a renewal of interest in the Appalachian South. The folk revival peaked, spurring young strummers to source songs and styles from the backcountries for Greenwich Village clubs. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson launched his “war on poverty” with a nationwide tour, producing a superabundance of lurid photographs, though the North Carolina tenant farmers he posed alongside resided in Rocky Mount, about four hours east of the mountains. (A local editorial, headlined “An Image Hard to Combat”—nicely mimicking Johnson’s language of war—then protested: “That family… would be regarded as living in the lap of luxury by [Appalachian] families… The President got a wee bit off his course in stopping here.”) When Johnson established the Appalachian Regional Commission a year later, the region’s borders were circumscribed based not only on culture but also sheer need, thus sealing its fate. Around the same time, David Hoffman, a greenhorn documentarian “visiting… from way up in New York,” shot Bluegrass Roots (1965) among the pine-draped Blue Ridges. A month after filming wrapped, Bob Dylan would go electric and fracture the folk scene’s edenic luddism. One of Dylan’s backstage detractors—though the reasons are variable as legend—was ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, who narrates Appalachian Journey (1990), a documentary that screens with Bluegrass Roots at Spectacle.

I sketch this little history to illustrate how Appalachia figures in the American imagination: sometimes bespoiled wilderness, sometimes untrampled paradise, or both. While the commander in chief enlisted the nation to aid its poor, the folkies rushed to preserve and propagate its riches, which were immaterial and analog. The poverty is both statistically verifiable and legally bounded, the development projects both impactful and a cynical form of corporate capture, the camera-toting strangers sincerely curious yet blind to their own biases. When those who document the region are rarely native to the land or kin to those they lens, their images are inevitably inflected with signifiers of felt difference. I kept wondering why Hoffman’s camera lingered on certain scenes—weathered lean-tos, scythe-shorn fields, roadside signs proclaiming “REPENT” and “JESUS SAVES,” a man salvaging parts from a junked automobile—even as I myself have done the same on visits home to North Carolina from Brooklyn. Every document of Appalachia feels fraught, suspicious: how can a filmmaker capture the region without narrowing their scope or ballooning into broad caricature?

Bluegrass Roots and Appalachian Journey take different approaches to this problem. The former, shot on black-and-white 16mm, follows the lead of musician Bascom Lamar Lunsford—founder of the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, the oldest extant of its kind—as he takes the crew around Buncombe and Watauga Counties, where he drums up pickers, strummers, balladeers, hoofers, farmers, and other country characters of his acquaintance. Lunsford’s status as an informed guide is immediately established: he is, a voice-over asserts, one of the few men in the region with a college degree; he reads poetry and cites Sir Walter Scott; he has worked as a schoolteacher, lawyer, newspaperman, politician, and has recorded traditional tunes for Columbia University. This is all very impressive, but it also plays into the very credentialism the folk scene had often rejected—a ballad hunter once said Jean Ritchie couldn’t be a folksinger because she had attended college—positioning Lunsford as both one of the band and able to hold forth on its music.

Hoffman and his crew rarely interject or appear on-screen, creating a feeling of disarming intimacy. The camera silently watches the musicians’ extraordinary performances on front porches, in open fields, or at public revues; it adopts the perspective of the car as it sharply wends around hills and dales. One scene, however, reminds you of who is looking. Lunsford takes the crew to a dance party in a private home, where the rug has been rolled up to make room for the gangly limbed teen hoofers, whose faces shine with a focused glow as they link arms and stomp out common rhythms, alongside a bluegrass string band (what Lomax would call a “country orchestra”). Their open-mouthed exertion is captured dizzyingly from within the dance, but at one point a cameraman lenses himself framed by a mirror, which shakes against the wall with the force of pounding feet, and in it we glimpse how the dancers must navigate around him. This clues us in: though placed among these people, he is not one of them.

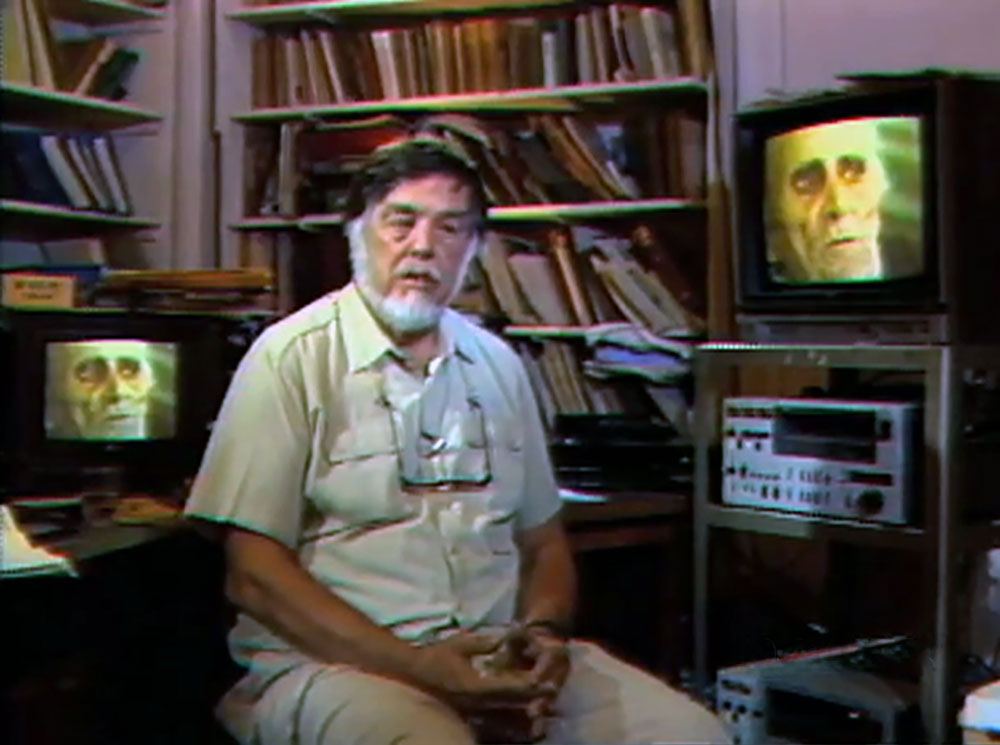

Suddenly it hits me that Lunsford’s version of the Appalachian South features not one person of color. One story goes that Lomax’s qualm with Dylan, that fateful night at the Newport Folk Festival, was in fact the predominating whiteness of his backing Butterfield Blues Band. And indeed, with Appalachian Journey Lomax expands Lunsford’s limited perspective. As narrator, he is careful to trace how the early European settlers drove out the Cherokee (the film features at least one indigenous singer); how white musicians cribbed songs and techniques from Black ones like Joe Thompson (late mentor of the Carolina Chocolate Drops); how workers didn’t just die passively, they fought, like Nimrod Workman, a singer and coalminer who rails against stripmining, which reduces jobs while disfiguring the landscape. But there is something too distantly anthropological in the film’s form, too overdetermined in Lomax’s analyses, that does not rise to its clever corrections to the historical record. Lomax appears in a cave-like office, before a tiny TV screen displaying the footage we have been watching, some of which features subtitles—many of which are wrong—for the mountain folks’ accents. Still, the second-generation folklorist makes it clear that his fieldwork has at least profited those whose songs he has recorded: “Before the folk music started,” one family recalls, they “often…had nothing to eat.” The folk revival and the “war on poverty” both disseminated art (photographs, music) in an attempt to alleviate deprivation, though in such a way as to fix that deprivation in people’s imaginations.

Last year, Hurricane Helene devastated western North Carolina, leaving at least 104 dead and ravaging entire towns, many of which had already been gentrifying due to tourism. (My parents, among the lucky, spent seven hours bailing out the floodwaters from my childhood home.) In the wake, Rhiannon Giddens, formerly of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, debuted a rendition of “Swannanoa Tunnel,” which Lunsford sings in Bluegrass Roots. (Giddens has previously critiqued Lunsford, saying his “Asheville folk festivals in the twenties were off limits to the melanin.”) The late 19th century ballad was first sung by Black prison laborers, hundreds of whom died carving the railroad tunnel, some shot by guards. Lunsford’s version, whose lyrics I won’t transcribe here, at one point adopts the punishing perspective of the white foreman. But Giddens pointedly omits this verse, instead placing herself squarely with the Black worker: “Hammer falling from my shoulder / All day long, baby, all day long / I’m going back to that Swannanoa Tunnel / That’s my home, baby, that’s my home.” Past and place are never settled for those who view Appalachia as neither hell nor paradise but as home.

Goin’ Across the Mountains: The Folk Music of Appalachia screens tonight, January 28, at Spectacle as part of “Best of Spectacle 2024.”