It’s a strange time for the cinematic experience. Filmmaking is currently halted as writers and actors strike over studios’ attempts to replace them with AI. The social (and social media) spectacle of Barbenheimer excited audiences about IRL theatergoing after a slow post-pandemic return. Streaming services disappear ‘content’ and ‘IP’ from existence as frequently as they don’t release physical media, while select cities enjoy a boom in repertory theatergoing. Venture capitalists and companies dumped billions of dollars, and seem willing to spend plenty more, pushing a fully immersive internet metaverse on consumers; the public response remains lukewarm to indifferent, yet the media breathlessly reports on every supposed tech genius picking up “the metaverse” dropped baton.

And yet, on the 70th anniversary of its in-theater inception, 3-D is the fad that keeps coming back. An evergreen novelty with yet-untapped creative potential, the format never quite topped its first wave, something NYC audiences can see for themselves with Film Forum’s upcoming series A Deeper Look: Hollywood’s First 3-D Wave, 1953-1954. I recently had the pleasure of interviewing 3-D Film Archive Founder and CEO Robert Furmanek, also known as the longtime personal archivist of Jerry Lewis, who programmed the series along with Film Forum’s Bruce Goldstein. We discussed the series, 3-D’s perpetual return, and the joys of stereoscopy.

Danielle Burgos: I know Film Forum has done a number of 3-D series with the Archives before.

Robert Furmanek: Well, I go way back with Bruce [Goldstein]. It's funny, we've talked about this occasionally—when I first got interested in 3-D, the theater to go to in the city was the Thalia, up at 95th and Broadway. A guy there named Rich Schwartz was the one finding these rare prints and running them, and Bruce apparently worked with him, so we very well may have met when I was 17 or 18 years old! But we didn't really cross paths until the late 80s. He was starting to do 3-D at Film Forum around 1988, and I had just moved back from L.A. and was really starting to build the archive then. I probably did my first shows with Bruce in the early 90s.

DB: This particular series is about going deeper into 3-D's first wave, and I'm glad to see an inclusion of a Mexican and an English film. Are there future screenings planned for the second and now third wave of 3-D, or an international series?

RF: That's a question for Bruce. I went to him six months ago and said, this is the 70th anniversary of 3-D film. We've done some big anniversary shows. In California we did a 50th, and then a 60th, but we've never really done a New York one. I said, look, we've got several dozen digital masters now, let's put something together! It took a lot of back and forth, and the schedule even now is still not complete. There's a number of films we've restored for Universal and they did not have digital DCP files on those first theatricals, so they're making them now. Fingers crossed that everything goes through, we'll be able to have those. That would be three titles getting a New York restoration premiere, which would be really really cool.

DB: I appreciate analog film and believe its preservation is important, but personally, I prefer seeing DCPs of 3-D movies. And there's no room for projector error, which you mentioned in the Archive's history was an early 3-D pain pointout of the gate even with people specializing in film projection, which is not often the case today. There's been a lot of general film projection issues people are just discovering as they're going out to see movies again.

RF: Like with Oppenheimer?

DB: ... (laughs). Yeah. A lot of that.

RF: I mean you want to talk analog, for the first twenty-some years of building the archive, it was all 35mm. We held what was the world's largest collection of vintage 3-D. We had left-right matched pairs on thirty of the fifty Golden Age features and had hundreds of screenings here. I'm not exaggerating! These were in many cases original 1953 prints. They all had been separated, and I found the left and rights, and recombined them, and got them back into synchronization. It's not difficult to project dual 35mm 3-D, but you have to be very careful, and you have to care. And unfortunately, even going back twenty, twenty five years ago, I saw so many sloppy presentations of analog 3-D.

There was one case where the operator started the film and the left and right prints were mis-framed. The left side was higher than the right. What that forces one eye to do is look up and the other to look down, which is not natural. I was sitting in the audience. It was a film I didn't have in the collection, so I was anxious to see it. I waited through the credits. We're two minutes into the film and we're still misregistered. I got up, went out to the lobby, and said to the person at the concession stand, "You've got to get the guy on the phone and tell him to rack the framing and to adjust that". She said, "Oh, okay, I'm sorry. I'm sorry". I went back and sit down. Now at this point, nobody quite understands. They think it's their glasses. People are taking their glasses off and they're complaining. And he's not fixing it! So I wait another minute and go back to the lobby and I said, "Okay, you're probably about 30 seconds away from a lot of refunds. You gotta take care of this". So she calls the booth and then says, "Can you talk to him?" She gives me the phone, and now this is a union operator I'm talking to. Probably pretty well paid for the gig. I said, "you've got to adjust your framing because you're tearing people's eyes out!" He said, "Can you come up in the booth and show me?" Yes, absolutely. So I went up to the booth. I went to the projector, and there's a big knob on either the left or right projector head that says Frame. What you do is grab this, and very carefully, because you're playing with people's eyes here, just move one slightly to get it back from here to here. That's all you have to do. It was a five second fix that took him five minutes to figure out how to do.

And that's just one story. I could tell you dozens. Talk about film, this [holds up enormous reel] is a 25-inch reel. This is what one half of one side of a 3-D film would have been on. If this was loaded with film, you'd be talking about 50 pounds of film. So multiply that by four, part one and two, left and right...you've got a couple hundred pounds of film. And now [pulls out tiny hard drive] it's on one of these! Woo hoo! I can put it in my pocket! So as much as I love film, digital is the way to go for these presentations. And even that's not completely foolproof, because digital errors happen too, but it eliminates most of the chances for mistakes.

DB: 3-D's second wave came with development of single-strip prints, trying to eliminate a lot of those projection problems. Do you also preserve those as well?

RF: We do; they're in much better condition because the 3-D image is on one strip of film. It solved the dual projector problem, but it introduced a lot of others. These wonky mirror box attachments that had to go on the front of the projector, usually the left and right images were stacked one above the other, and the attachment would align them, and you had different controls on there to adjust it. So there you had all other opportunities for mistakes. Man, I remember going to see some of those in the 80s and you'd walk in and they'd have a third of the image on the ceiling of the theater. You'd have all kinds of wonky shading going on because they'd be putting strips of tape across the projection board to try to mask some of the image. It was a mess.

DB: I saw a couple of those prints at Quad Cinema's Coming At Ya! series a while back. Some were badly salmoned and weren't in the best of condition, but they actually did a good job projecting what they had, I thought. I don't know if you got to see any of those.

RF: I did! That was a very controlled situation because Harry Guerrero, who did the series, came in with his own lenses, his own glasses. It was very supervised, and that's great for a special series like that, but out in the field, all bets are off. More often than not, they were screwed up. Part of the thing too, with the films from the 70s and 80s, they went really heavy with the gimmicks.

DB: Literally coming at you.

RF: Oh yeah, exactly. There were some films in the 50s that did that, like Spooks with the Three Stooges, but it's a comedy short, it's 18 minutes. And if it's not nailed down, it's thrown at the camera. But to do it for a 95-minute feature, it overstays its welcome. And a lot of the 70s and 80s films went overboard in that direction. One of the things for me that's very gratifying about getting a chance to restore so many of the 50s films is people are seeing that, no, these filmmakers really respected the stereo window, they didn't abuse that opportunity to pelt the audience. They're getting re-appraised, which is a nice feeling.

DB: I was singing the praises of Inferno when I finally saw a non-anaglyph print of it. It was like time traveling! It's so lush and beautiful and it's in dimension. You feel like you're there!

RF: I think one of the things that makes the vintage films so special is you're not looking at post-photography conversions. These aren't things that were done with CGI or any digital trickery. You're seeing real, discreet, left-right views that were captured by the cameras. For the most part, considering these bulky, very cumbersome camera rigs—Cease Fire! is a wonderful example of this, because it was photographed just a few miles from where they were actually fighting in Korea during the war. They captured these really marvelous stereo images. As you mentioned with Inferno, it's a window into another time, and it allows you to immerse yourself in the clothes and the cars and the styles of that era. To me that's something that's very magical about it, and I've always had an affection for 3-D from that period for that reason, and that hasn't changed. I still feel that way.

Quite frankly, a lot of what's been done over the last decade or so, we call them 2.5-D, because they're so conservative. They're so afraid of one person in the audience having a little bit of eye strain that they really minimize the depth of a lot of these films. There have been exceptions. Hugo is one of my favorites from the last wave. But Scorsese wanted to emulate the look of 1950s 3-D. In fact, he screened things like House of Wax and Kiss Me, Kate, and Dial M for Murder for his crew and said, this is what we're going for with Hugo. And they succeeded beautifully. But that, unfortunately, is the exception.

DB: I'd mentioned AI earlier, but Mark Zuckerberg was pushing so hard for the Metaverse. I feel like he built that and no one came. It was rejected wholesale, whereas even with early 3-D, when theaters were trying to draw audiences away from television, even though there were so many issues getting it off the ground, audiences still showed up. It seemed like the Metaverse was an ideological failure versus 3-D's human error issue. Do you have any thoughts on the ideology behind something like the Metaverse and this constant 3-D, fully-immersive realm that people do not seem to want?

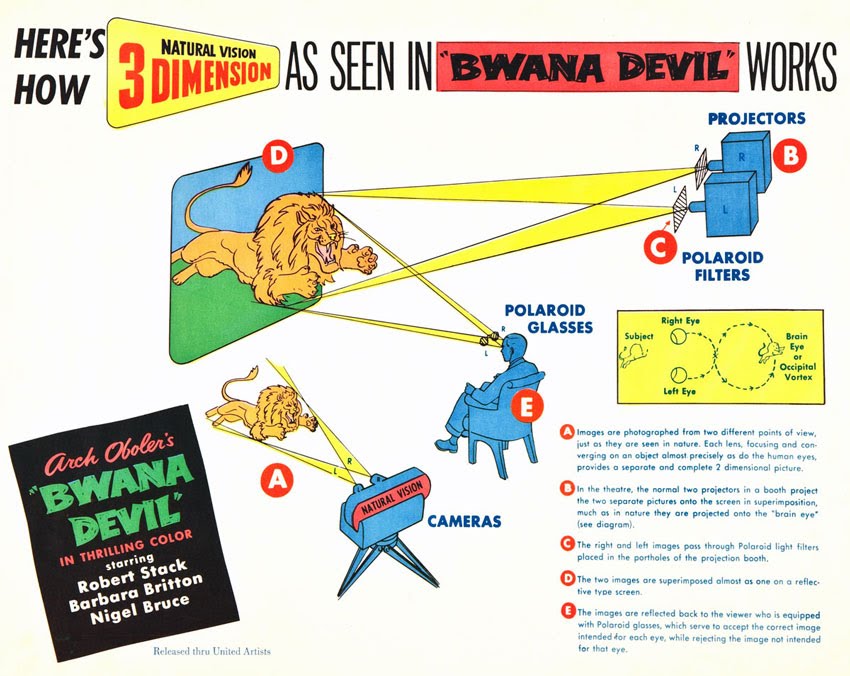

RF: In 1952, This Is Cinerama premiered and was an enormous success. That used three projectors and a huge wrapped-around screen, very immersive. It was something like five channel stereophonic sound, and that more or less kickstarted interest in 3-D. I think at that time, a lot of it was exhibitors trying to get people out of their homes, away from the little 12-inch black-and-white TV screen, and back into the movies. And for a short window, 3-D gave that. The films were sold as fun and immersive. And the studios tried all different types of films, it wasn't just horror or science fiction. We had westerns and comedies and musicals. It worked for a very short period. As far as how that would relate to today, I don't know. It's hard to say. I think the failure of the whole metaverse, if it has failed, I haven't stayed on top of it all that much, maybe it's just because people don't want to live life in an imaginary world. It's not really living, is it?

DB: How does that compare? Because 3-D does seem to keep coming back, even though people have said, oh, it's a gimmick. It's come back several times now, and people still like it.

RF: Well, I used to make this analogy: it's kind of like the circus. It was fun when it would come to town, and you'd go and have a great time. But you don't want to go to the circus every week. 3-D works in moderation. You don't have to have everything in 3-D. But if it's done well, and it's a good film, and the photography is good, it's a real great ride. One of the nice things about the films from the 50s is that they don't overstay their welcome. They're 80 minutes long, not these three-hour epics with no intermissions. I mean, even the shortest of 3-D films had an intermission for technical reasons! So, you're not asking people to stay in their chairs for the entire afternoon.

DB: I know Avatar, the original, the recent sequel and the ones coming out later, were and are intended to be in 3-D. James Cameron is very particular about the technical elements that he's using. But, they are also three hours long.

RF: I can respect that. My biggest beef with them is, put an intermission in there! The concession stand will love you for it.

DB: Do you think 3-D has a viable future?

RF: I think for limited use, for the right kind of film. One of the issues I've had with a lot of the [2-D to 3-D] conversions is that the whole style of cutting and editing now is so rapid. I was a stereo photographer for decades, and I shot a lot of my own stereo slides. One of the things that is very captivating about them is the opportunity to not rush through them. If you see an image that captures your imagination, you can stay on it. The older films didn't do that rapid style cutting. Films that do that now, I think it's very hard to appreciate the work that may go into certain shots because they're on and off the screen in such rapid-fire succession that it just doesn't resonate. I think 3-D works better for films that aren't cut like that. But on the other hand, that could just be a generational thing too.

DB: Had you seen Blake Williams' 3-D experimental feature PROTOTYPE? When it showed at MoMI, he didn't mention this before, but told the audience after, there were two different images in each channel. And if you felt like closing one eye or another, you would get a different movie experience. I feel like it's still untapped, the medium's potential. I don't know if the Archive would be interested in preserving any of 3-D's more experimental uses.

RF: Well, that's an interesting technique. It's called 'double film' and it goes back to 1924. There was a short done by Pathé called As You Like It. It basically used exactly what you're talking about, where they would have a scenario and then for the wrap-up to the sequence, they'd have two versions. And the left eye could watch one version, the right eye could watch the other. Phil Tucker did that in Robot Monster, and nobody knows this because prior to our new restoration, it hasn't been seen in seven decades, but there are scenes where Ro-Man, the character in the big gorilla suit...

DB: Oh, yeah, very familiar.

RF: There are scenes where he's showing the destruction of the planet. Phil Tucker put different eyes of destruction in the left and right sides. They're short, only maybe four or five seconds, but you've got this really intense retinal rivalry happening, and it's deliberate and it's uncomfortable. The irony there is when Godard did it in Goodbye to Language, everybody thought it was so revolutionary, but...Phil Tucker did it on Robot Monster! It's been done before.

DB: You have made my week learning Godard was beaten out by Robot Monster. I am ecstatic to hear this.

RF: It's true! That's the fun of restoring these films, because we're bringing things back to life in a way that the filmmakers intended. All the creative people that came together to create these films intended them for 3-D, but for the most part, they haven't been seen that way in seventy years. We've been very lucky to have sold out houses when we premiered 3-D Rarities at MoMA in 2015. That's a nice feeling, so I'm hoping the Film Forum shows do well. We're doing our best to promote them, and get the word out.

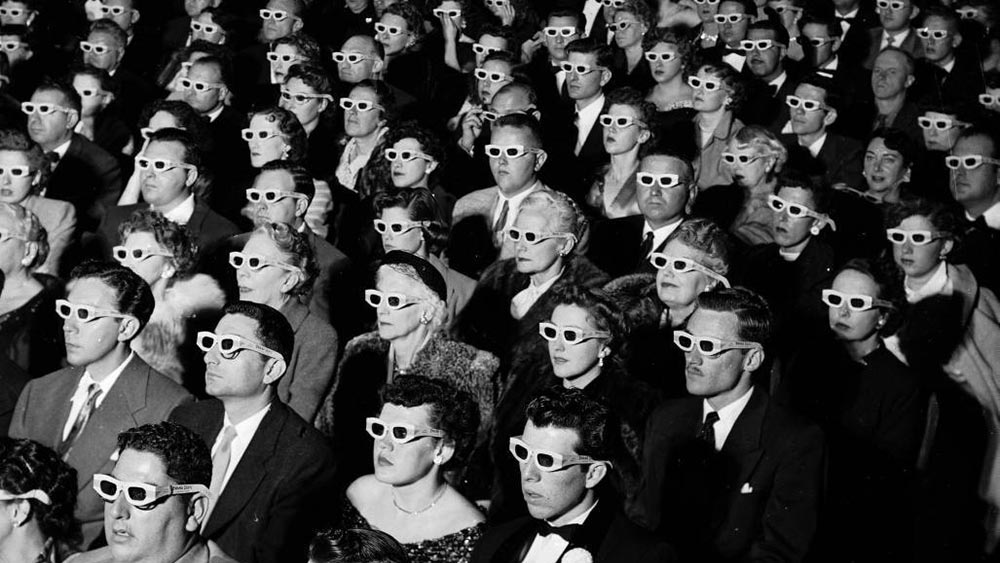

DB:There really is something communal, more so than movies usually are, where people really get a kick out of seeing 3-D in a group. You would be able to speak to that better than I, but every time I've gone to a 3-D screening, it’s an event.

RF: It's not something that you can easily do at home. For a period, and thankfully, it was available for a while, you could buy a 3-D display. You can still get projectors and VR headsets for those that want that immersive other-world effect. But I think the group type of a vibe that you get with the film...I mean, let's face it, these films are 70 years old, and there are things about them that haven't stood the test of time. Robot Monster is a great example. It was silly in 1953, and 70 years later, the silliness is amplified, but it's part of a fun experience with an audience. And there is a little bit of that roller coaster thrill ride thing where there might be some startling off-screen effect, like the man with the paddleboard in House of Wax. That aspect makes it a group event and a lot of fun.

DB: Do you see 3-D having a continuing future? Will there be a fourth wave? I'm glad people are back in theaters, but the studios really seem to be trying their darndest to eliminate humans except as this unfortunately necessary ticket-buying component.

RF: I don't know. I don't see 3-D ever being mainstream. I think it's going to continue to be isolated to special event type films, and films that really lend themselves well to using stereoscopic images for storytelling purposes. Not just a way to charge extra for tickets, that's not going to work.

DB: I don't know if technology has made it easier or more difficult for you to track down materials. Is it harder to get access or to track down 3-D originals?

RF: One area that has helped a lot in the internet era is catalogs that are now online. Archived databases that you can search. I'll tell you one story about that which I think is very telling in its own way. There was a musical short film done in 1953 in England called Harmony Lane, and it was never released in 3-D. But I was doing research at the BFI database online, and I found elements on Harmony Lane. There were quite a few elements labeled 35mm negative. So I contacted them, and this is where it got a little wacky. They wrote back and said, Well, yeah, we do have multiple reels of elements or negative on Harmony Lane. But they had gone to a book that was published in the 1980s called "3-D Movies" by a guy, R. M. Hayes, published by McFarland. And it's loaded with errors. I can't begin to tell you how many mistakes are in that book. According to the Hayes book it was never finished in 3-D.

So the BFI tells me, well we have all these reels, but it's not really a 3-D film. We can't help you. And I pleaded with them. Please don't go by that book. Please, can you pull these out of the vaults and inspect them, look at them. It took quite a while before I finally convinced them to do that. And lo and behold, they found they had complete left-right elements of it. There's one example of the searchable online database helping you get so far, but there's still that very human component where you have to get someone on the phone and they physically have to go in the vaults and see what they have. It has helped. One of the challenges years ago, everything had to be done by mail. I go back enough to remember when you had to send letters and phone calls, and that's how I found most of the prints that built the Archives. It was a lot of work.

DB: It still sounds like a lot of work.

RF: Yeah. But it was fun. I had a blast doing it. And something like this series is an opportunity to see all that research and effort come to fruition, when you can sit with an audience and experience it on the big screen. It's a nice feeling.