On Thursday, August 8, I stepped out of the humid summer heat and into the pleasantly air conditioned Museum of Modern Art for the classiest of all cinema events: a celebration of the 50th anniversary of Tobe Hooper’s 1974 classic, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. [Ed. note: the original release styles chainsaw as two separate words.] I was looking forward to this particular screening for months because of the venue itself. If you frequent the movies at MoMA, you’re probably familiar with some of the colorful regulars, who often attend as many screenings as they can. This can lead to a more unique theatrical experience when the programming is on the more… confrontational side. I wanted to see their reaction to one of the more notorious entries in the horror canon. However, the plethora of black TCM shirts—the rep cinema equivalent of wearing band merch to a concert— made it clear this wasn’t going to be the everyday MoMA crowd.

This was not only the 50th anniversary of the film’s release, but also of the museum welcoming The Texas Chain Saw Massacre into its film collection, a move that honestly still feels radical today. When introducing the screening, MoMA curator Ron Magliozzi contextualized this decision within the “New Hollywood” era, when American directors pushed creative boundaries amidst a film industry in flux. Uncertain about the future of Hollywood, MoMA programmers Larry Kardish and Adrienne Mancia actively broadened their search for exciting work that was happening outside of the major coastal hubs of New York City and Los Angeles. Not discriminating between avant-garde circles and the B-movie drive-in circuit, they leaned heavily into showcasing and collecting works by everyone from Stan Brakhage to Ralph Bakshi. These discoveries included a gritty independent horror movie made by film students from Austin, Texas.

Like it does for many horror fans, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre holds a special place in my heart. I was a lucky kid when it came to movies; I was free to watch whatever I wanted (for the most part) and my dad was especially entertained by my begging to rent horror movies whenever I stayed with him. Even so, I remember popping in a VHS of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in secret, afraid of what was on the tape. I watched it in the daytime—fitting, since most of the film takes place in broad daylight—and it felt even more sinister that way. Maybe I thought I wouldn’t be so scared if I watched it in the afternoon, my fear disinfected by sunlight. Just like the characters in the movie, that thought only tricks you into walking straight into hell.

You probably already know the general concept: a group of young people are road-tripping through rural Texas when they run out of gas in a town that deindustrialization has left behind. In their search for help and fuel, they fall victim to a multi-generational family of cannibals, and are picked off one-by-one by the chainsaw-wielding Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen). Only one member of the group, Sally (Marilyn Burns), manages to escape, becoming an early example of the horror genre’s “final girl” trope.

The film is infamous for its visceral horror; its ingenious filmmaking conjures an environment of slaughter with very little blood and gore, and the film’s malevolent tone has stood the test of time for viewers. This malevolence is rooted in its sense of realism, established in the film’s opening, in which crawling text and voice-over informs the viewer that what they are about to see is based on true events. The soundtrack, which avoids musical orchestration in favor of a collage of mechanical and metallic noises that creak and groan in the background, creates an alienating anxiety throughout. The details of the film shoot itself, with its daily 100-degree plus temperature, malodorous unwashed wardrobes, and real bones and animal carcasses littering the set, seep into the viewing experience. Watching the film, there were so many moments where I caught myself thinking, “I know it smells crazy in there.” All of these elements make up a wicked assemblage that imbues the film with a cursed spirit.

I truly couldn’t say how many times I’ve seen The Texas Chain Saw Massacre; much of the film is burned into my brain like the sun feels burned into the picture itself. However, seeing it on the big screen with an appreciative audience (a decent number of whom indicated they were first time viewers), is an elevated experience. Moments I’ve witnessed countless times made me wince, exacerbated by the blaring sun that cooked the cast, cooked the rotting meat on set, and possibly cooked the celluloid itself. The iconic ending scene, with Leatherface dancing against the sunrise, his chainsaw revving so loud and piercingly that it prompted some people, myself included, to plug their ears, is simply magical in the theatrical setting. When the picture abruptly cuts to black, the crowd burst into cheers and applause.

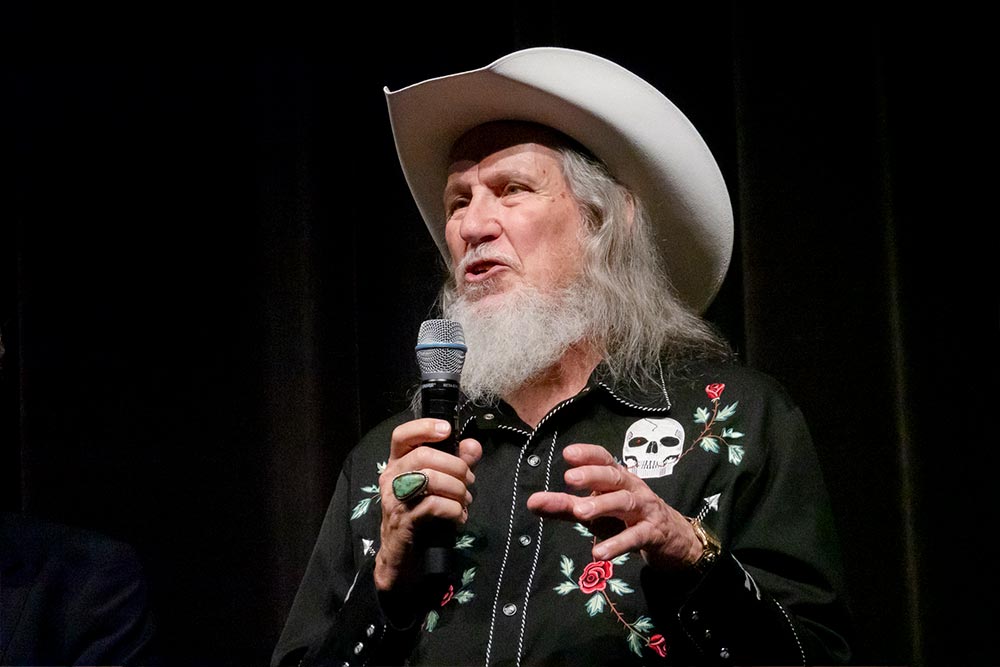

The infectious excitement continued with the Q&A portion of the evening, as Magliozzi and programmer Caryn Coleman welcomed screenwriter Kim Henke, cinematographer Daniel Pearl, production manager Ron Bozman, and actors Teri McMinn (Pam) and Edwin Neal (“Hitchhiker”). There was a surprise appearance by actor John Dugan (“Grandpa”) as well, who announced himself from the crowd and hopped up onstage. Magliozzi and Coleman had sharp questions for the group about the film’s legacy, gender in the horror genre, and the political climate the film was made in and its parallels to today. I can’t say we received answers to some of these deeper questions, as there was quite a bit of crosstalk among the large panel, which contained some big personalities, most notably Neal and Dugan. However, everyone shared their surprise at the cultural footprint the film has had, what Henke described as “utter shock, considering the way it began—the reviews weren’t exactly sterling.” And, there were entertaining anecdotes about the shooting experience and how the film has shaped everyone’s lives in different ways.

Teri McMinn, who did not continue acting after the film wrapped, stood out as someone who has embraced the Texas Chain Saw connection only relatively recently. McMinn appears in not one but two standout moments. The first she refers to as the “red shorts scene,” where her character, Pam, gets up from a swinging bench outside Leatherface’s house and Pearl’s camera, low to the ground, drifts under the bench and follows her to the front porch. The second is her gruesome encounter with Leatherface, where he hangs Pam up on a meat hook in a scene so carefully edited that it is miraculously free of blood and gore. McMinn recalled not thinking highly of her performance until decades later, when she finally accepted an invitation to appear at a horror convention and heard from fans about their love and sympathy for Pam. Considering the dearth of acting opportunities that arose for her immediately post-Chain Saw, she noted the disparity in what doors opened up for Hooper, Pearl, and crew members in the more “technical” roles, versus other members of the cast.

It was a rowdy Q&A for MoMA, for both the panelists and the spectators—a mention of serial killer Ed Gein even received a funny hoot from an audience member. The discussion highlighted the unique cultural space that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre occupies, likely because of an institution like MoMA opening its arms to it all those years ago. The film continues to be a genre cornerstone for the horror community while also esteemed by cineastes, in addition to being recognized for its significance in the history of American independent film. Few horror movies are represented on “Best Of” lists for both Sight and Sound and Fangoria Magazine.

The cast and crew in attendance reflected on this as well, with some of them in suits and others in cowboy hats, some of them with awards to their names (Ron Bozman has had an especially prestigious Hollywood career, having won a Best Picture Oscar for producing The Silence of the Lambs, 1991) and others more heralded in the genre film landscape, making regular appearances in the horror/comic book convention circuit. The tenor of the gathering, to me, was reminiscent of a reunion of college friends (which for some individuals it was), where you get to see the different roads traversed and the shared locus that brings everyone back to their youthful days. In a rather sweet moment, Neal addressed the crowd to thank the film’s fans, saying, “There’s not many films that can fill a hall like this after fifty years. You don’t know what you people mean to us. You’ve taken us all over the world!” It was a birthday party, indeed.

Photos by Edwina Hay