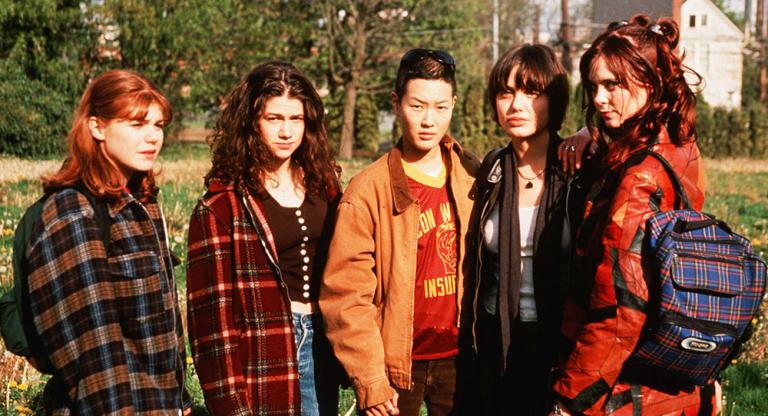

Annette Haywood-Carter’s first feature, Foxfire (1996), is best watched in a group. It’s one of those movies where the ensemble is made up of young actors (anchored by Hedy Burress, Angelina Jolie, and Jenny Shimizu), most appearing in their first film, all pulsating with a communal, infectious exuberance.

Rarely shown since its release and available commercially only in less-than-stellar quality, the film plays at Nitehawk on 35mm as part of programmer Cristina Cacioppo’s new series “The Outskirts” (an outgrowth of her Screen Slate column, which previously featured Foxfire). Whether you and your friends continue the night by giving each other stick-and-pokes by candlelight and listening to Mazzy Star in the wooded depths of Prospect Park is up to you.

Director Annette Haywood-Carter will be appearing in person for the screening. We discussed bringing together the fledgling cast, the film’s tumultuous release, and its growing legacy.

Mackenzie Lukenbill: Whenever I show Foxfire to someone for the first time—which is often—I’m struck by how much it seems like a film that should have developed a much larger following in the last five years or so. Do you know when the last time it played on 35mm was?

Annette Haywood-Carter: Yeah, 1996, when it came out. It was really kind of catastrophic. We were supposed to come out in the spring; it was going to be marketed as a high-school spring-break movie, and then Goldwyn went into bankruptcy. They canceled the release and pushed it to the summer, and then it wound up lining up with one of the really big summer movies, like Twister or something. And because Goldwyn apparently didn't have any other film that they were packaging and putting out at that time, they didn't have the power to hold onto the screen. We just got kicked to the curb. At that point they decided it wasn’t even worth it to pay for advertising, so they pulled the advertising and opened it for one weekend. It just came and went and didn’t have a shot.

ML: It seems like a common story for a lot of films made by women in the mid-’90s, especially first-time directors. I’m thinking of movies like Alex Sichel’s All Over Me [1997], or Lesli Linka Glatter’s Now and Then [1995], or Sarah Kernochan’s All I Wanna Do [1998], which almost constitute a micro-genre of movies from around only twenty-five-ish years ago that don’t have Blu Ray releases, don’t play rep series very often, and are getting scarce, which is kind of scary to me!

AHC: You know, Cristina had trouble finding a print. I thought I had one, but to be honest, I've moved so many times, and every time I move something doesn’t make it or gets stolen, so somewhere in there I lost Foxfire.

ML: There is a print on eBay right now for $500.

AHC: That’s crazy. I wonder if it’s mine.

ML: There is an “HD” copy on Amazon, but it's in the wrong aspect ratio. The crop is completely wrong and so is the color grade. The compositions and lighting in this movie are really gorgeous. On Amazon Prime, in one of the shots inside the house where you have all of the girls blocked in a single frame, Hedy Burress is just completely cropped out.

AHC: The Super 35mm format was really important to me. I really love that aspect ratio. I love composing ensembles where you can come in really close with the lens, but still get them all in the shot.

A lot of this is new information to me because I’ve seen it pop on TV, but I’ve never watched it. It's almost painful for me to sit and watch a movie that I have made. And I don't know why that is. I actually tried to watch it recently; I thought, Well, maybe I should watch it before I get to New York. I didn't get through the opening credits.

With a lot of distance and perspective I’ve come to appreciate what we were able to accomplish, and how rare it was, to have those gorgeous compositions and that gorgeous production design. It was my first movie, and it’s so hard for anybody but the top directors to get the time to set up and light shots like that. I’ve also developed an appreciation for it historically; I can see its value in where it sits on the timeline of women’s movies and women’s stories.

ML: In thinking of it as maybe ahead of its time, I don’t know if you’ve seen that show Yellowjackets at all, but superficially it’s about a group of girls living in a decrepit house in the woods, and it takes place in 1996, but there are some lighting set-ups in the attic of the house that I swear were lifted right from this movie. Oh, and there’s a Mazzy Star needledrop.

AHS: It was maybe ahead of its time, but also shouldn’t have been! I moved to LA from Athens, Georgia, and my crowd of friends there—we were friends with the B-52s, my little brother’s best friend was in REM. And then I got to LA and was just surprised; it felt like Hollywood was way behind the times, that there was so much interesting cultural stuff happening and Hollywood just hadn’t caught up. We got some really strong negative reactions to the movie when it came out, and it surprised me. I just didn’t get it.

There was a review in Variety that was such a vicious attack on me as a filmmaker. I was working at Amblin as a script supervisor and someone called me and said that there was a rumor around town that the critic must have been an old boyfriend because they had never seen him take on a director like that, this personal and this mean. Another critic said something like it was too slick, too beautiful, and they couldn’t take it seriously—like what does that even mean? I’m not supposed to have beautiful images in a rebel girl movie? Just really generalized attacks that felt like they didn’t know how to talk about the movie.

ML: One thing interesting about some of those reactions is that apart from setting it in the ’90s and not the ’50s, it’s pretty faithful to the book.

AHS: Yeah, it's fairly faithful. The project had been developed by another producer and director, and the script that I first read was oddly kind of off-target. It was a novel set in the ’50s written by a screenwriter with an ’80s sensibility. There was this scene where Legs gets beat up in prison that just felt very ’50s. It was just very false for teenagers in 1996. It was a little maddening.

ML: I'm sorry for relying on IMDb for some of this information, but it lists the credited screenwriter as having their only other credit as a producer on Beth B’s Salvation!?

AHS: No, it’s not the right person. The screenwriter wasn’t happy with the film so she took her name off. The name that’s on the movie, Elizabeth whatever, I don’t even remember, isn’t anyone—it’s fake. I always wondered if she regretted it once Angelina became a really big deal.

ML: Had Hackers come out yet when you cast Angelina?

AHS: It had. I didn’t see it until much later. Angelina was only nineteen when we cast her. She was in that very adolescent space of creating an identity for herself as a person, and around the roles that she played. Hackers was, you know, Angelina on the surface, where she’s just being the tough girl. I think she wanted to go deeper and be vulnerable and damaged and relatable.

Angelina auditioned for Goldie first, and it wasn’t right. I asked her to come back and audition for Legs. She didn’t want people to know who her father was, and I didn’t know; I didn’t know who she was. And her audition for Legs—I’m not exaggerating, I just sat there going, Oh my God, this is a movie star. I can’t believe this is happening to me. I always talk about her as a female James Dean, but I think she was bigger than that, honestly. So we offered her the role. And she turned it down. I asked her if she would please just meet with me before making her decision. So we met in a coffee shop on Wilshire, and she came in with a bunch of switchblades and put them on the table. And she said, “So I’m trying to decide which kind of switchblade Legs would carry.”

So I was like, OK, she’s definitely wrapping her mind around this. So we sat there [for] over an hour and connected, and she took the role.

ML: And this was Jenny Shimizu’s first film?

AHS: Yeah, I was having a really hard time casting Goldie. Jenny was a Calvin Klein model; she had been discovered in a motorcycle repair shop. The casting director came in one day and showed me a picture of Jenny, topless, leaning on a motorcycle and said, “If she can act, would you cast her?” and I said, “Yeah, if she can act.”

The whole cast was very young. Hedy Burress hadn’t acted in a movie before either; she was a theater actor and in college. We had a nationwide call, and I was watching this tape with like a hundred girls on it from Chicago, and that’s where I found Hedy. And the studio looked at the tape and said no. And this was back in the day, when directors really got to decide, right? The director was the king of the castle. They said she wasn’t pretty enough. I said, “Okay, can we do a screen test?” At the screen test I told [cinematographer] Tom Sigel and the hair and makeup team, “In the movie she’s going to look very natural, we’re not going to do any of this. But for this, make her look like a movie star.” They looked at the screen test and let me cast her.

ML: Newton Thomas Sigel wouldn’t have been a huge name yet either. There’s kind of a remarkable foresight with all of these decisions.

AHS: I think my superpower is my ability to kind of really find that talented needle in a haystack, you know? I started out wanting to be a cinematographer and just wasn’t able to break in during the ’80s; all the doors were closed to women, which is why I became a script supervisor. I was interviewing tons and tons of people—I have a strong visual language and I wanted it to be collaborative. And Tom had just finished that movie that was his big break—

ML: The Usual Suspects [1995]?

AHS: —but prior to that, he had been doing a lot of second unit for Oliver Stone. He had shot a handful of smaller features, and every film would look different. He was very much a collaborator and wanted to give the director exactly what they wanted. I loved it. We would just mind-meld.

Bob Rafelson came to the editing room while we were editing Foxfire—he was looking at one of the actors to potentially play Jack Nicholson’s son [in Blood and Wine (1996), a part which went to Stephen Dorff]. So he watched some of the footage, and afterwards his assistant came back, kind of sheepish, and said, “I hope you don’t mind, but he wants to watch some other footage.” And it was really random scenes. A few days later I got a call from Tom, who said he had just gotten out of an interview with Bob Rafelson. Foxfire hadn’t come out yet. He said [Rafelson] had watched all this footage and started asking him very specifically, “Was this your idea or the director’s idea?” I said, “Well, what did you say?” And [Tom] said, “I told him the truth. Sometimes it was my idea, sometimes it was the director’s idea. Sometimes I just don’t know.” And Tom got the movie.

ML: Foxfire has a really bold look—I love all the color contrasting in the lighting, especially in the hideout house where you have all of these different frames within frames and the foreground and background are different color temperatures. Did you have any reference points? Some of it reminds me of, like, Jimmy DeSana or Marilyn Minter photos.

AHS: It’s funny that you say that, because I was really obsessed with still photography. But I’ve never had a reference point going into a movie. If I ever did, it was unconscious, and I wasn’t aware of it. I find it extraordinarily difficult to do things like pitch decks; I’m like, “It’s in my head. It doesn’t exist yet.”

But as for that house, a lot of the credit for how this movie looks has to go to the production designer, John Myhre. The house really pissed the producers off because I looked at thirty-five other houses before that one. And that one we were allowed to alter in any way we wanted—it was just a really old abandoned house on what eventually became a bird sanctuary. So we just started taking out pieces of walls, both so that the camera could travel and so you could see from one room into another. If I wanted a little depth on the right of the frame, we could just poke a hole in the wall. The tree that Jenny Shimizu is sitting on [inside the house] during the tattoo scene—we just put that tree in there. It was the best of both worlds; it was a real location that we got to treat like a soundstage.

ML: So I have to ask for the lesbians—is it correct that Jenny and Angelina’s relationship started during production? Did that affect the vibe of the ensemble at all?

AHS: Yeah, it happened right there [on set]. I can see moments in the scenes of Legs and Goldie together where there’s just an extra depth of tenderness to her rage. And Legs is really fueled by her concern for Goldie’s well-being, so it affected [the film] in a positive way.

So when you said “for the lesbians” I actually thought you were going to ask me a different question.

ML: What did you think I was going to ask!

AHS: So you know the scene on the roof where Legs and Maddie are talking, and they touch each other’s cheeks. Well, in the script and in what we shot, they kissed.

ML: What!

AHS: And the company made me take the kiss out.

ML: No way.

AHS: And a year later the head of the company told me it was a mistake. Because right after, suddenly, you have like Ellen DeGeneres kissing on her show and there was mainstream marketing value in the lesbian kiss, or whatever, and we didn’t have one because they forced me to take it out. It’s a beautiful scene, and the center of it still holds without the kiss, but I look back on it and I think, Really should’ve kept it in there, guys. I’ve never told anybody that before.

Foxfire screens tonight, February 24, at Nitehawk Prospect Park on 35mm, followed by a Q&A with director Annette Haywood-Carter.