When you stumble upon the Hoover Institution’s online moving image archive, it won’t take you long to figure out what ties it together thematically. The front page promises “Firing Line 2-Inch Videotape Preservation” and “Videos from Reagan’s 1976 Presidential Run Now Online.” If you don’t remember Ronald Reagan’s 1976 platform, it was largely the same as his 1980 one: strengthen the military, cut government programs, deregulate industry, and “end welfare fraud” (the origins of the Republicans’ obsession with welfare fraud is the subject of this great episode of Code Switch). But do you remember Firing Line? From 1966 to 1999, William F. Buckley Jr. presided over this bone-dry PBS talk show, with its Brandenburg Concerto opening theme and its zero-frills approach to the talk show format. Buckley would spend 59 minutes skewering liberal guests with his barbed sophisms or refereeing rhetorical deathmatches between progressive and conservative academics. The Hoover Institution archive hosts a good part of the show’s 1,500 episodes. What else? Ah, here’s a good one: a four-minute introduction to an episode of Free to Choose, Milton Friedman’s public television effort at spreading the neoliberal gospel to the masses, delivered by Arnold Schwarzenegger: “I came from a socialistic country where the government controls the economy. … But me, I wanted more. I wanted to be the best.” With the beguiling innocence of a five-year old, Schwarzenegger gushes about the power of the market to unleash our potential and make us happy, just as it allowed him to “parlay [his] big muscles into big bucks.” What exactly are we being sold here?

The Hoover Institution’s mission involves “advancing ideas that promote economic opportunity and prosperity, while securing and safeguarding peace for America and all mankind.” One way it does this is by granting fellowships to such figures as Chicago School economist Thomas Sowell, neo-imperialist economic historian Niall Ferguson, and former Secretary of State and war criminal Henry Kissinger. One of the weirdest recordings in the Firing Line collection is the 1986 roast of William F. Buckley, which features Kissinger along with neo-Keynesian economist Kenneth Galbraith and man-about-town Tom Wolfe. Wolfe’s performance is priceless, taking detours to harpoon New York Times editor John Bertram Oakes as “the arch-liberal editorial writer of all time” and DSA-cofounder Michael Harrington as “the only socialist in America.” You can also see Wolfe on a 1981 Firing Line episode with the Spenglerian title “Is Modern Architecture Disastrous?” in which Wolfe muses on the irony that the architectural designs of the Bauhaus’s committed leftists would within a few decades be used to house the offices of the biggest corporations in America. There’s a smugness to Wolfe and Buckley’s repartee that seems to derive from what they perceive as the underdog nature of conservative thought within academia and culture at large. Buckley frequently describes progressive political positions as “fashionable” and sees himself as the defender of an imperiled intellectual tradition, as summed up in his 1955 mission statement for the National Review: “There never was an age of conformity quite like this one, or a camaraderie quite like the Liberals’.” Heritage Foundation founder Edwin J. Feulner went so far as to call Buckley “the pioneer who opened the marketplace of ideas to conservatives.”

From a 21st-century vantage point, this might seem like a familiar story: the Right considers itself hemmed in by a leftist intellectual hegemony that is primarily concerned with identity politics, feminism, political correctness, etc., a hegemony that is especially visible on college campuses and in the infamous liberal media. But in Reagan’s time, American conservatives had another thing to be concerned about: capital ‘C’ Communism and its very real hegemony in the Eastern Bloc. This is why Schwarzenegger lambasts his “socialistic” homeland (which is quite an overstatement of the facts) as a drab place where “you can hear 18-year old kids already talking about their pensions” (at least they can look forward to having pensions), and why Buckley loved to offer a forum for repentant socialists, such as ex-revolutionary Max Eastman and Czech former Communist official Eugen Loebl (upon whose show trial Costa-Gavras based his 1970 film The Confession).

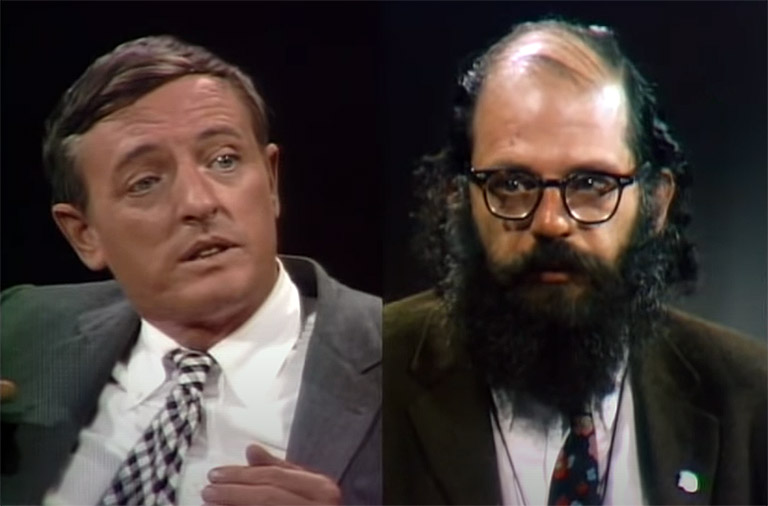

Loebl appears in a 1977 episode called “What’s Up with Eurocommunism?” in which Buckley displays some of his own Marxological erudition, making observations like “It is really thought of as a Leninist accretion on Marxism to say that there is only a single road, and that that road must be dictated by the central party.” The rest of the interview consists of Buckley baiting Loebl into condemning various European Communist parties’ motives and then humbly agreeing. Some of Buckley’s subjects, however, are not as easy to shepherd. Allen Ginsberg makes it especially difficult for Buckley, refusing to answer any of his questions directly. But determining who comes out on top is a tough call, as Buckley manages to troll Ginsberg into hitting all the high notes of a hippie caricature.

Some of the best material in the archive is, without a doubt, the Q&A’s with Californian high school students that Ronald Reagan did while on the campaign trail in 1976. The students of Encina and Oak Grove High School are especially trenchant: the conversation is regularly brought back to questions about decriminalizing cannabis, which, since the interview is unrehearsed and unedited, Reagan has to hedge and dodge to the best of his ability. Although the drug enforcement legacy of the Reagan administration is well known — the mandatory minimum sentences, the first lady’s “Just Say No” campaign, the sharp rise in the prison population — he pretends to give these kids the benefit of the doubt, trying to lecture them about “new and unknown properties” of marijuana—for example “that men could suddenly begin developing feminine characteristics from the use of it”—without sounding like a complete asshole. All things considered, he does a surprisingly decent job.

The Hoover Institute’s archive is a portal into the collective mind of what Feulner calls, with a modicum of braggadocio, the “overwhelming underdogs” of the American intellectual arena: the Chicago School neoliberal economists, the Reaganites, and the adherents of what columnist George Will called Buckley’s “intellectually defensible modern conservatism.” The key difference between National Review-style conservatism and Trumpism may just lie in that little phrase, “intellectually defensible,” and is at the core of what makes the Hoover Institute’s archive such a valuable resource: it gives you an opportunity to hear conservatives you might actually want to argue with.