Less than a year after her performance of a one-woman “visual and aural song cycle” entitled “Let’s Face the Music,” Zoë Lund (née Tamerlis) dropped out of the Manhattan School of Music. She was 16 and frustrated, like anyone with political convictions in private education. In cinema, she saw a more direct means of expressing her principles. Lund worked with Edouard de Laurot, whose films may or may not have provided fronts for weapons smuggling, and Abel Ferrara, whose films may or may not have provided fronts for drug dealing. (In 1991, Lund wrote about the latter: “He still doesn't get it—but knows its value. Like pearls before a swine who nonetheless knows he can trade in those pearls for a ton & a half of crack!”). She starred in two New York grime classics—Ms. 45 (1981) and Special Effects (1984)—before co-writing her own with Bad Lieutenant (1992). In Harvey Keitel’s drug-addled march to absolution, she saw Christ, and “the perfect distillation of the revolutionary myth,” according to an interview published in the Danish film journal Balthazar in 2002.

Hot Ticket (1993) was commissioned by the IFFR in 1993. Its two shots run just over 90 seconds. In the first, Lund wanders through the brightly lit lobby of Rotterdam’s Luxor Theater. The camera retreats before her, struggling to contain her in the frame. In the second, she approaches the theater’s box office, where she exchanges a full syringe for a ticket. In voice-over, she reads: “That which is not yet, but ought to be, is more real than that which merely is,” before treading past the camera and disappearing into the crowd on the sidewalk outside.

Cinema, reality, and heroin are the elemental forces at play on her journey from inside the frame in shot one, to outside the frame in shot two. In 1986, Lund called heroin “the drug of disillusion” and wrote, “On heroin, you can cry. You can feel loneliness and fear. Above all, you can feel the anguish that is ‘transformed into history.’” Cinema, too, mustn’t be considered an escape. Lund disparaged Ferrara’s navel-gazing in Dangerous Game (1993)—“there are dozens of films which deal with this stupid shit, and my God, I have never, never in my life, confused a film with reality!” For Lund, heroin and cinema cannot be tools to turn away from reality, but rather means of seeing it more clearly in order to envision something better. The film’s ticket is neither sobriety nor another dose; it buys passage neither into nor out of the theater, but rather from the merely is to the ought to be, by whatever means necessary.

The French film theorist Nicole Brenez wrote that Lund’s off-screen dialogue in Hot Ticket “necessarily founds all culture of protest.” In its brevity, Hot Ticket pares Lund’s principled vision of cinema down to its essentials. The film was her only directorial effort; she died of an overdose in 1999. Only available on a poor magnetic transfer until a recent discovery at the Eye Filmmuseum, Hot Ticket joins last year’s Poems in this latest surge of interest in the artist. Its exhortation is no less intense for its mystery. In Lund’s speech near the end of Bad Lieutenant, written, allegedly, mid-nod and five minutes before shooting, she sketched out the imperative: “We have to give, and give, and give crazy. ‘Cause a gift that makes sense ain’t worth it.”

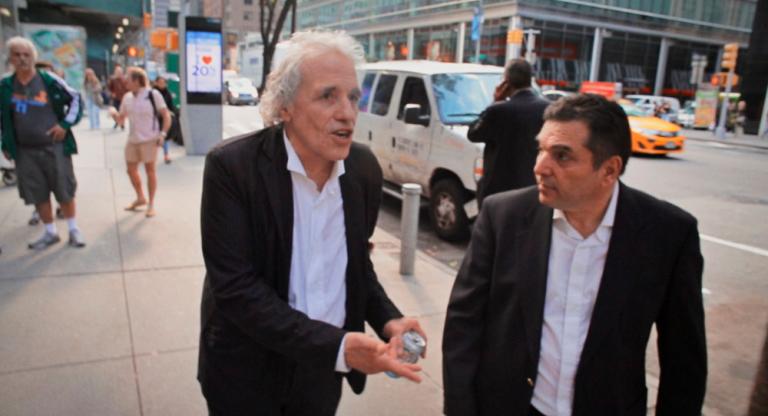

Hot Ticket screens tonight, July 16, at Anthology Film Archives as part of the series “ZOË LUND.” It will be followed by a 35mm presentation of Lund and Edouard de Laurot’s Story of an Ordinary Man. Tonight’s event will also be introduced by Stephanie LaCava, Manon Lutanie, and Robert Lund.