The first thing we see in Yasujiro Ozu’s I Was Born, But… (1932) is a truck wheel spinning without traction in a muddy rut. The truck carries a father, Kennosuke (Tatsuo Saito), his two young sons, Keiji (Tomio Aoki) and Ryoichi (Hideo Sugawara), and their family’s furniture from the Tokyo city center to their new home in an outlying suburb. They’re stuck on a dirt road in a vast, barren plain, with the only nearby structures being the utility poles that line the road, stretching into the distance. It’s the kind of place most people would describe as the “middle of nowhere.” And this is why it is significant — because it is nowhere.

Since writing on Ozu has long featured grand and not entirely substantiated proclamations about what is or is not Ozuian, allow me to make one myself: this bereft and indistinct road may be the most Ozuian landscape in his filmography. That familiar couplet of themes—tradition and modernity—which recurs throughout his films is represented by the two points on the horizon where the poles converge in either direction. One lies east, towards the memory of a bygone Tokyo (flattened in the Great Kanto Earthquake and rebuilt) which this family is leaving behind. The other points west, towards the Americanized future in front of them (complete with neat green lawns and white picket fences), slowly emerging from an economic depression. But the truck’s stalled progress indicates that Ozu neither romanticized the past or the future. Life was happening here and now, on this lonely road in the space between the old and new, the east and west, Japan and America. Stranded in the “middle of nowhere,” Ozu made movies.

As part of their Ozu retrospective, Film Forum will screen I Was Born, But… with a performance by Ichiro Kataoka, a master benshi, or silent film narrator. The rare appearance of a benshi in US theaters is a good opportunity to reflect on the connections between Japan and America in the early 20th century, not just in I Was Born, But… but also in the film culture that developed through migration between the two countries, and which was fostered in large part by benshi. Though Ozu never made any films in America, he was profoundly shaped by this history. The critic Shigehiko Hasumi notes that Ozu’s cinematographic genealogy (and that of his longtime cinematographer Yuharu Atsuta) can be traced to Henry Kotani, a Japanese-American actor and cinematographer who got his start in Hollywood and went to work for Shochiku’s Kamata film studio in 1920 at the recommendation of Cecil B. DeMille. Kotani shot Shochiku’s first film, The Island Woman (1920), and his Hollywood training established a standard for the cinematographic style and division of labor at Kamata, where Ozu and Atsuta both got their start.

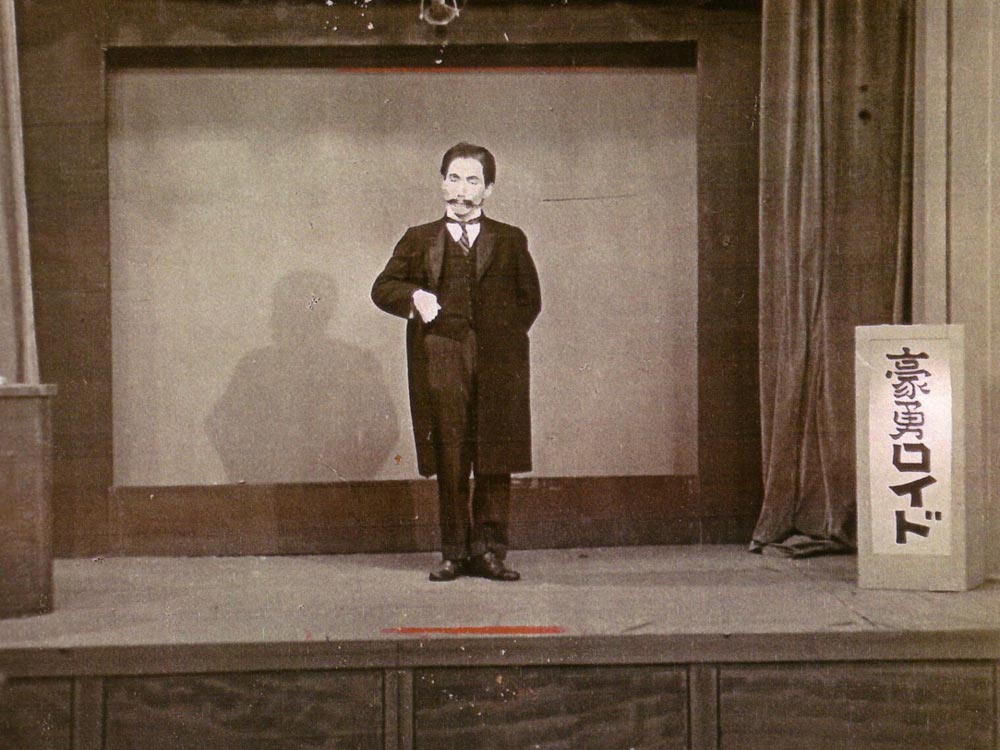

According to Hasumi, the Hollywood inflections in Ozu’s early films are not merely the result of his personal preference for American films. An aspiration and curiosity toward Hollywood was systematized into film production at the Kamata studio from its very beginning, and in the wider culture of film exhibition in Japan. The sight gags in I Was Born, But… and Keiji and Ryoichi’s antics owe a great deal to Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, whose films would surely have been shown in Japan with a benshi providing not only narration but also explanations of cultural context to help audiences understand them. The Kamata sound stages and backlots where the film was shot did not necessarily imitate American suburbs, but conveyed the domestic ideals associated with them through their patchwork of vacant lots and new houses. Unobstructed by buildings, trolley lines and utility poles feature prominently in outdoor scenes, heralding the developments that will pop up around them. But their geometry also clutters the frame, cutting harsh and unsettling lines across the sky. An ambivalence towards this modern life hides behind the outwardly cheerful scenery.

Perhaps Japanese immigrants in America, tempering their expectations of opportunity with the reality of survival in another country, felt similarly about their own surroundings. If we take the idea of a midpoint between Japan and America literally, we find ourselves in another so-called “middle of nowhere” — that is, in Hawaiʻi. Between the illegal annexation of the islands to the US and the onset of WWII, Hawaiʻi was an attractive destination for Japanese immigrants seeking work or even an entirely new life abroad. Many of the original waves of migrant laborers to Hawaiʻi in the 19th century had completed their grueling plantation contracts, and stayed back to establish Japanese communities, which of course included their own theaters. Thanks in large part to research by media historian Denise Khor, we know that benshi based in both the US and Japan toured their own collections of imported Japanese films throughout Hawaiʻi, which became a hotbed for Japanese-American film culture. Benshi provided immigrants with glimpses of their homeland through their films and their narration. Outside of theaters, they hosted screenings in ad hoc venues like temples or town halls, or simply threw up a sheet between two trees and projected their films under the stars.

Did Japanese audiences in Hawai‘i in the 1930s have the opportunity to see I Was Born, But…? Though it is extremely difficult to find records of film screenings from that far back, we can’t rule it out as a possibility. Ozu’s previous films weren’t that popular, and likely wouldn’t have been selected by theater owners or benshi abroad, who preferred exciting films with a rousing emotional impact and a message that could strengthen the morale and sense of Japanese identity among immigrants. However, I Was Born, But… was Ozu’s first major critical and commercial success, and it is easy to imagine immigrants finding the story appealing. In Kennosuke’s move from the city to an isolated community where his boss lives, would they have seen their own move to the islands? Did fathers see in Kennosuke’s kowtowing to his boss the indignity they endured in the sugarcane fields under harsh overseers, all for a chance at a better life for their family? Did children identify with the boys’ struggle to integrate into a new school, and to fight the bullies who play a cruel game of pretend in which the weak are slain by the strong?

In the film’s decisive moment, Keiji and Ryoichi find out from a home movie shown at the house of their father’s boss that Kennosuke makes himself into an object of ridicule in order to be liked by the boss and his coworkers. It is another moment mixing cheerfulness and uneasiness, with the crestfallen expressions of the children contrasting the humorous film being shown, in which Kennosuke pulls funny faces and acts like a clown. With their image of him as a strong and commanding father shattered, the boys stage a hunger strike in protest. This link between cinema and the action of the strike manifested itself in Hawaiʻi too. As Khor points out, the first major labor strike among cane workers in Hawaiʻi began with a 1908 meeting to discuss unionization in the Asahi-za, Honolulu’s first Japanese theater. In striving to bolster unity among Japanese immigrants, benshi were catalysts for these early labor movements. In narrating and explaining films, benshi not only could transpose the story and lesson of the film to a local context, they could also potentially reach audiences beyond the Japanese and forge multi-ethnic solidarities. For example, Khor recalls an anecdote about Tochuken Namiemon, a benshi in Central California, who adapted his narration to audiences of Japanese and Mexican agricultural laborers by mixing in English and Spanish in his performances.

For their role in promoting a sense of ethnic Japanese pride and unity and their proximity to Japanese labor movements, American benshi were prime suspects of the federal government after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. And after the mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps, the benshi tradition withered away, especially as sound films ensured their obsolescence. But some continued to perform on occasion. Naomi Sodetani, a sansei benshi and filmmaker in Hawaiʻi, has written movingly about the life and work of her mentor, the late Kamesuke Nakahama, who came to the islands when he was sixteen years old. During WWII, he was interrogated by the FBI, and after Japanese theaters in Hawai’i were forced to close and their films destroyed, he became a restaurant worker. His benshi activities were mostly relegated to special events at the Honolulu Academy of Arts, the University of Hawai’i, and the Hawai’i International Film Festival. Still, as Sodetani mentions, memories of Nakahama’s celebrated performances remained potent among those who had experienced them:

Senior citizen gatherings keep Nakahama busy as an emcee. “People still come up to me and say, ʻNakahama-san, when will you do one of your shows for us? Only you can make us cry.’”

Ozu never directly referenced Hawaiʻi in his films. The closest we get to such a reference is the “Blue Hawaii” bakery, which features as a location in Where Now Are The Dreams of Youth? (1932). This gives some indication of what image of Hawaiʻi loomed in the minds of Japanese citizens at the time. Even so, this hardly qualifies as a substantial link between Ozu and Hawaiʻi. But I do think something of Hawai‘i is captured, if only inadvertently, in I Was Born, But…. After all, Roddy Bogawa titled his 2004 film about his childhood in Hawaiʻi and the LA punk scene after it, so there must be something to it. Maybe it’s the general idleness of the children, who escape school and slack off in a way that befits a sense of “island time.” Or it could be that the blend of Japanese and American cultural signifiers feels familiar. Or maybe it’s just the sight of Ozu’s dirt road in the middle of nowhere that moves me and which leads me to claim it, because it could be anywhere at all.

I Was Born, But... screens on Sunday, December 3rd at BAMPFA with live piano accompaniment by Judith Rosenberg, the start of a three-month retrospective, Yasujiro Ozu: The Elegance of Simplicity.