Sky Hopinka’s blurred views of Indigenous gatherings acknowledge and protect the sanctity of these events. Our eyes are not drawn to faces, which are obscured. An extractive relationship to the spectacle of bodies is circumvented. Instead, we perceive fluid movement, color, and collective spirit. We hear soaring music. Bodies glimmer and a cappella choruses score syncretic documentary fissures. Audio recordings of Christian Sacred Harp songs combine with visuals from a powwow in Oregon.

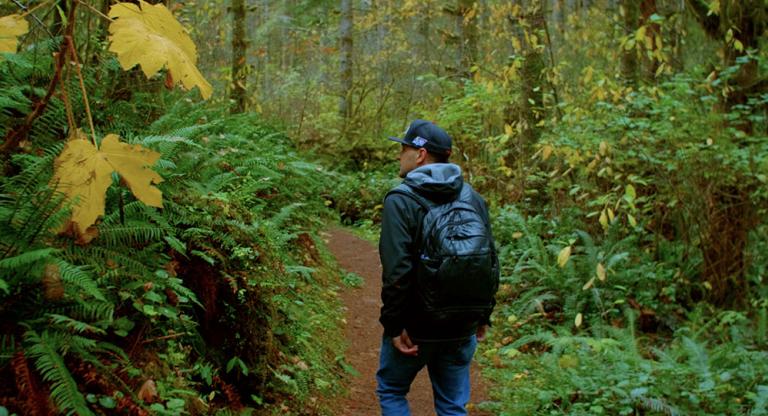

I’ll Remember You as You Were, not as What You’ll Become (2016) is a twelve minute video that screens on a loop in the permanent collection galleries at MoMA. Singing cuts to instrumental drones and polychrome ceremony cuts to darkness. Unfocused orbs dot the screen and then sharpen to reveal a forest at night. Roving lights sweep across trees. Then a single voice: “Yeah. Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Spirituality. Uh-huh. Yep. Mm-huh. The Mother of Earth. Yep. Mm-huh. No, I don’t know where you can get peyote. No, I didn’t major in archery. No, I didn’t make it rain tonight. Ah, yes, it’s absolutely true that Indians never tell a lie. Yea, a lot of us drink too much. Some of us can’t drink enough. This ain’t no stoic look, this is my face.”

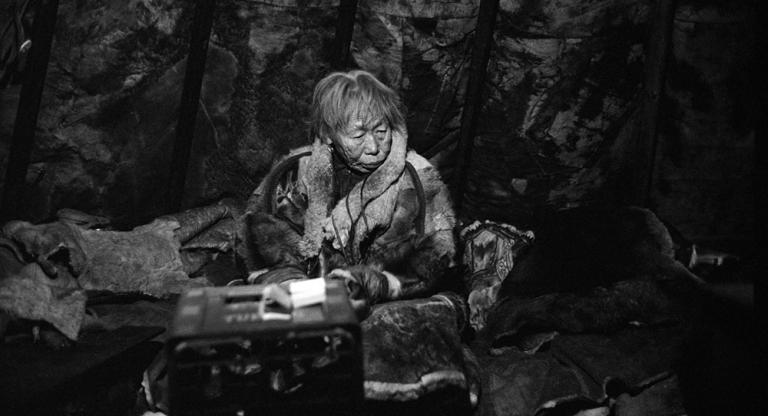

The footage of Diane Burns (1956–2006) performing this poem is contained in the lower-right corner of the frame, humbly miniaturized so that her words can swell and glow with other visions. Burns grew up in the Western deserts of her father’s Chemehuevi people and also in the Great Lakes forests of her mother’s Anishinaabe. In the 1970s, she moved to the Lower East Side and became active with art communities at the Poetry Project, Nuyorican Poets Café, and A Gathering of the Tribes. In 1981, Contact II published Burns’s poetry chapbook Riding the One-Eyed Ford, with a foreword that notes, “this book is a true story.” An excerpt from a poem in this collection, “Big Fun,” is also sampled in Hopinka’s video. “Big Fun” contains a 49 song, which is an American Indian song with some English words, coded to speak to multiple audiences in different ways. In 1989, Burns and Bob Hollman collaborated on Alphabet City Serenade, a video starring Burns and narrated by her poetry as she walks through rubble on Avenue D: “I’m a hopeful aborigine. Trying to find a place to be. Oh, East Village, ai yi yi yi yi yi . . . ”

Burns spoke truthfully of displacement, smoke, prayer, genocide, gentrification, television, and a night at the bar. While Burns and Hopinka never met in person, her poetry became influential on his wandering ethnopoetic practice, which favors intuitive and musical arrangements of witnessed material. I’ll Remember You as You Were, not as What You’ll Become is an elegy to Burns and also a “rumination on different ideas around reincarnation as [Hopinka’s] tribe, the Ho-Chunk nation believes in it.”

When you reach the work in the galleries, one of Hopinka’s silkscreened calligrams greets you on the wall. The work reformats a poem into the figuration of a bird, breaking words into limbs of letters. Burns spoke in interviews about looking up to see eagles drawn in by the music of powwows, circling high above because somewhere in their bones they could remember these songs that had echoed in the skies from gatherings of generations past. Hopinka’s work uses cinema to explore how time embeds in sound and images, how sound embeds in landscapes, and how landscape can embed in sound.

I’ll Remember You As You Were, not As What You’ll Become screens in an installation at the Museum of Modern Art through January 31. Tomorrow evening, January 18, MoMA will host a Variety Show Celebrating Diane Burns and the American Indian Community House in the gallery.