When the 76-year-old filmmaker André Forcier speaks about artistic creation and writing, he refers to it by the word inventing. Forcier directed Bar Salon (1974), which was referred to as “the Greatest French Canadian film of its time” by the magazine Cinema Canada, when he was 25 years old. But his age is not what is of importance, it is his courage and independence, which he shares with the Quebecers of his generation—filmmakers who produced a singular body of cinematic work throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s—that warrants admiration.

In a creative field that remains rife with bad ideas, negligible budgets, and an overreliance on formulas, this cluster of Québécois films stands alone and represents an outpouring of unadulterated creativity. It’s difficult to imagine that any organization today would ever venture to fund such extremely non-commercial output, but this happened in Canada for two decades. What is most shocking is that Forcier and his contemporaries—Robert Morin, Micheline Lanctôt, Mireille Dansereau, and many more directors whose films are showing this April at Anthology Film Archives as part of “Quebec-Core”—remain almost unknown in the United States.

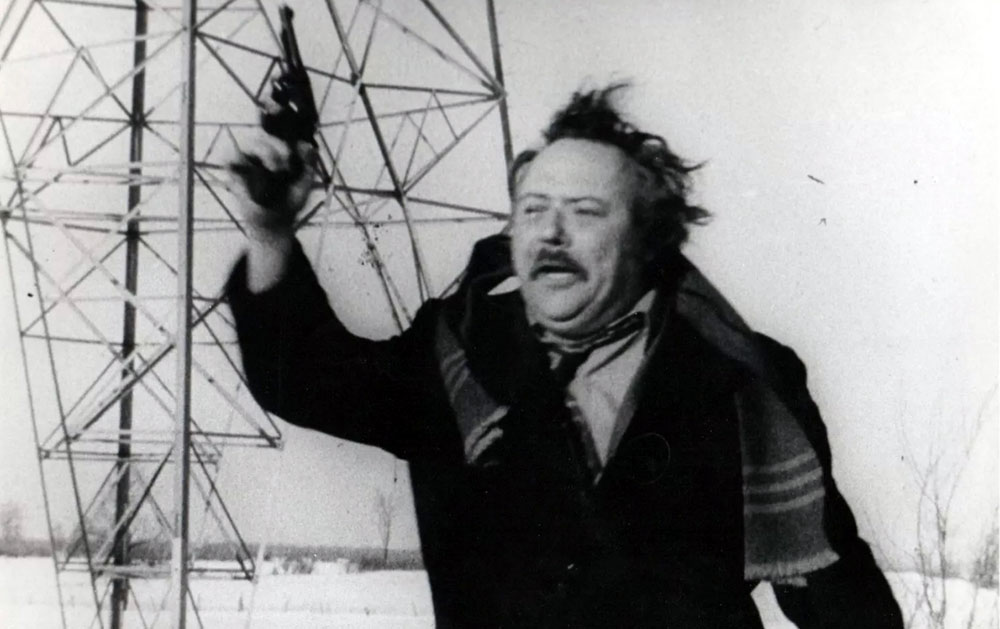

My co-programmer Sean Price Williams and I recently interviewed Forcier over the phone. He discussed his recently restored film Au Clair De La Lune (1983) and the United States debut of several of his best films from his home in Longueuil in anticipation of his first Q&As in New York City.

Luke Rathborne: We’re really excited to have you coming in. When we were putting together the Quebec-Core series, the first movie Sean and I saw was Au Claire de La Lune [1983].

André Forcier: Well, it's being remastered. The quality is very good, although they have to work on the subtitles.

Sean Price Williams: Yeah, it's gonna be great to see a good copy because we've only seen it in a kind of muddy VHS. [Laughs]

AF: Yeah, it was very shitty. You'll see a huge difference, we saw a huge difference.

LR: The cultural delegate, Jean-Pierre Dion, who we worked with alongside Jed Rapfogel, was mentioning that a lot of the effects in the film are optical effects.

AF: Yeah, they're all optical effects, all of them—we were crazy. The film was shot in the winter of ‘78 and ‘79, but the technical release was in 1983. When we shot the film two actors got sick because it was 35 below zero celsius while we were shooting during the night.

Self-service gasoline is popular in Quebec now. There's nearly only that now. But when we were running with a car shooting fire from the rim, we could have blown up all of the neighborhood because… Yeah, I guess we were crazy. [Laughs]

SPW: I think it looks like the coldest film. Sometimes it's really hard to capture how cold it is. I've worked on movies and I always get disappointed when it doesn't look as cold as it, felt but your movie feels very cold. Why was the film’s release delayed?

AF: When I finished shooting the film, I was hired by the National Film Board of Canada. At that time, the National Film Board of Canada was producing fiction films like La Lune. The director of the French unit of the National Film Board told me that he liked La Lune very much. “We're gonna co-produce the film,” he said. But we didn’t shoot everything. There was some little scene missing and that's why there's a flashback in the film. I usually hate flashbacks but I consulted with my mentor, Gilles Carle, a famous filmmaker in Quebec and Canada. And he said, “André, the best flashbacks are made by guys who hate flashbacks.” [Laughs] So I invented the flashback.

But I never met somebody who told me this is an artificial flashback. I think it was the final scene and I split it into two or three parts. Bernard Lalonde, the other producer, and I invented the voice-over just to put all the things together. The voice-over is kind of poetic, but it's part of the story. For instance, the character of Bert, he's an orphan from a long line of orphans, you know, de pére en fils, from father to son. The idea of giving him an ancestor that did not exist at all came when we wrote the voice-over.

LR: In the film, it’s said that he’s an Albino from the invented land of Albanie.

AF: Albanie. Albanise. He’s from the country of the albino: Albinie. I saw that somebody told me that I was talking to Jacques Marcotte. We co-wrote a bit of the structure of the film, but we were not on the same page. I mean, we're still friends but I said to Jacques, “I’m gonna finish the structure myself because we don't go at the same pace.” So I did the structure of the film—I wrote the script and the structure. But we did some practice with the two actors: Guy and Michel. There was a French Theater in Ottawa and they were practicing. I was in Ottawa working with them just to make the dialogue better.

LR: I wanted to ask you about Bar Salon. It came out of a period when women weren't really allowed in bars. Is that correct?

AF: Yeah, women were only allowed in what we called the bar salon. I mean, there were taverns only for men. And in 1985, they passed a law so that women would be allowed in taverns.

LR: The period in which you made Bar Salon coincided with a moment when younger people in Quebec wanted to break from associations with the church, right?

AF: Yeah. Well, my upcoming film is called Ababouiné and the action takes place in 1957. It’s about all that—the beginning of that crisis. We hope for the best way to sell it, but it's a very anti-clerical film. [Laughs] We were colonized by the English and by the church. The relationship between the English Canadian and French is not good at all, but I mean, we live in the same country.

SPW: Well, we know which side we're on. We’re also interested in how some of these films got the money to be made. Was it through the government?

AF: Well, with Bar Salon we had $58,000 and my salary was $2,500, and the people who played in it were professional actors who wanted to invest half of their money, and some amateur actors.

SPW: Was that film kind of successful?

AF: Yeah, it had a very good release, but it was in black-and-white and at that time people didn't want to show [films] in black-and-white. But, there are some articles—that I can show you—that say that it was the best Canadian film ever made at that time.

LR: There was a pretty short gap between Bar Salon and L’eau Chaude, L’eau Frette [1976].

AF: Yeah, but I shot a 36-minute film called Night Cap [1974] in-between. It was very well received. It was produced by the National Film Board. After that, I did L’eau Chaude, L’eau Frette.

SPW: All the Québécois films that we were watching from the ‘70s don't seem very commercially oriented, but I think that there's an independence there.

AF: You know, the idea of Bar Salon—I had a girlfriend and she left me. She left me and she was having a beer with her new boyfriend in a bar, and the bar was closing. That’s the only thing I knew about that bar, that it was closing. That’s why I invented a bar that was vanishing: the bar of Bar Salon.

LR: I was just going to say there’s a scene in L’eau chaude, l’eau frette when she's showing her pacemaker to…

AF: That’s me in the film. I wanted to act with a simple girl, you know? Three hours before the shoot, my assistant told me, “Well, since we bumped the schedule… Who do you want to replace [Amoureuse in the film]?” I said, “Carole Laure,” who was a big name at that time in France being [in Giles Carle’s films] at that time. She’s a real beauty. So we called her and she said yes.

SPW: I think with Claire de la lune, the films start to become more fantastical. There’s more of a dream logic in them. Is that true, is that film a changing point?

AF: There’s some magic in L’eau Chaude, L’eau Frette—the pacemaker that boosts the motorcycle. I was gonna receive the National Order of Quebec, which is given to important people, but I didn’t. My wife Linda was going to introduce me with a clip from a film I had a lot of success in France called Le Vent du Wyoming [1994]. It also had a very good release. It stayed one year in the cinema, in one cinema. We released it in one cinema but it was still there for one year on the screen.

SPW: So it's a special audience in Quebec I think, where maybe these films are commercial. [Laughs]

AF: I don't know what commercial means, I just want to write good stories that do not annoy the spectator, the viewer, you know? [Laughs]

SPW: It’s a good rule. It’s amazing that these films have not really made it into America before.

AF: I'm not sure the script would be bought by Hollywood.

SPW: No, definitely not. The films are too good. They’re so close to America but could not be farther at the same time.

AF: What’s fun about being a Quebecer is to feel as at ease in New York as in Paris, because we're American somewhere. It’s a mixture of a European and American sensibility in Quebec. That's what makes it so unique.

LR: Early on, it seems that you had a lot to say about class, particularly about the experience of members of the lower class struggling in urban environments.

AF: I'm living in the Longueil section of Montreal, in a working-class section. My house is paid and I'm not rich. [Laughs] As long as your house is paid, you have a driveway, and free parking, it’s all right.

Au Clair de la Lune screens this evening, April 11, at Anthology Film Archives with director André Forcier in attendance for a Q&A. The series Quebec-Core runs through April 19 at Anthology Film Archives, and Screen Slate members receive AFA member pricing for all screenings.