Introduction to the End of an Argument (1990) is the result of a collaboration between the Lebanese-Canadian artist Jayce Salloum and the Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suileman. The film comments on the absurdity at the heart of Israel’s occupation of Palestine, especially how Western media has capitalized on racist stereotypes to warp and control the perception of the Intifada—the Palestinian resistance to Israel’s occupation. Its presentation at Anthology Film Archives forms part of a program curated by the Palestinian artist Emily Jacir, whose own experience with censorship and media backlash for speaking out against the Israeli occupation is well-documented.

Salloum and Suileman’s film juxtaposes scenes of everyday life shot in Gaza and the West Bank with a vehemently racist charade of stereotypical portrayals of Arabs in Western films, cartoons, and network TV. This contrast invites the audience to ask: How do these images inform the United States’ views and foreign policy on the Middle East? But above all, the film offers a trenchant portrayal of the West’s relationship with the Middle East, questioning the architecture of power that determines what is universally remembered.

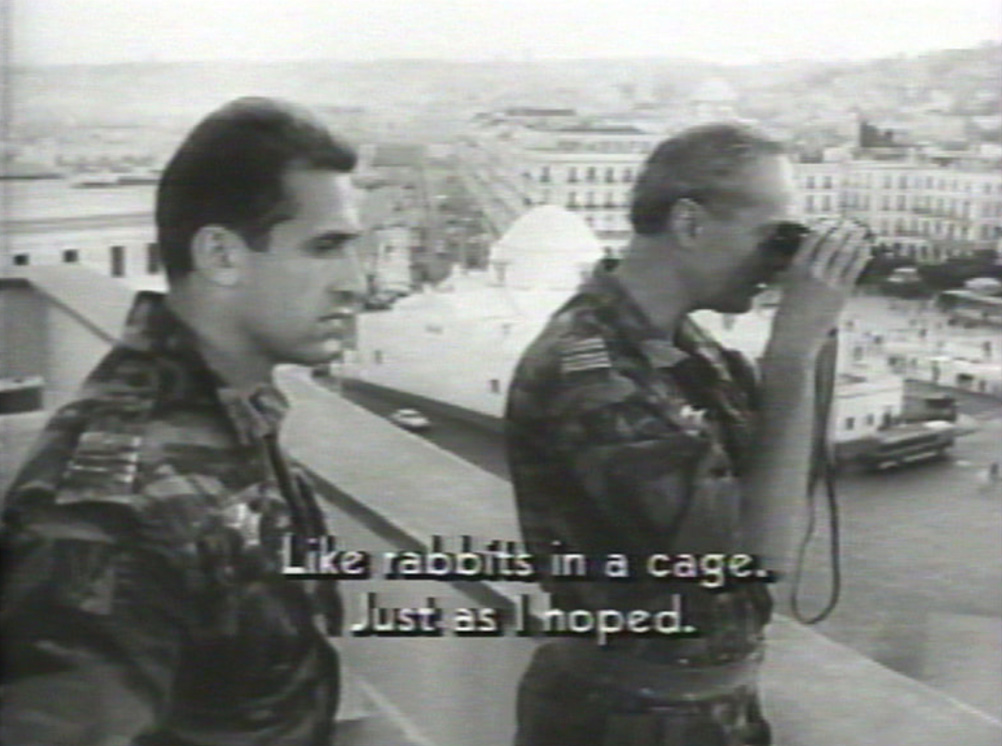

Although Argument is only 40-minutes long, its numerous tonal shifts, as well as its constant visual fits-and-starts, demand patience. But in return, the film delivers a powerful meditation on mainstream cinematic aesthetics, subverting the formal tenets of Western media through playful mimesis. By placing excerpts from films like The Delta Force (1986), in which Chuck Norris single-handedly murders hundreds of Arab men, alongside footage that depicts the daily lives of Palestinians, Argument stresses the West’s nonsensical and distant understanding of the Middle East. The broken clips, re-appropriated images, and stammered speeches from Western broadcasters that make up Argument—a film that can be characterized as a disjointed series of choreographies and restless stutters—allow Salloum and Suleiman to interfere with known white supremacist narratives that are peddled in mainstream media.

Argument greets the viewer with a sweet, open view of a lush treescape. Then, interrupting the slow, melancholic opening song a playful voice exclaims: “I don’t know the song, do you?” She laughs. “And I can’t sing it, I’m sorry!” As the music continues, the camera moves from shots of anonymous street pedestrians to letters on a black screen that address the viewer again. These words read: “possible beginnings.” The camera shifts, as if trying to stabilize itself, and a voice in Arabic says, “All people have a country of their own, and we also wish to have our own country, which is the Palestinian State.” At its core, the film seems to address this very statement. Argument’s alternately sweet and defiant opening insists on developing its own definitions of characters and relationships: between the US and Israel, and between entertainment and stories routinely censored by Western media. The film does not just make light of, or destabilize, the Western images it cites, it also uses them to show how they are inherently tied to the West’s debate regarding Palestinian statehood.

The film also misuses the formal elements most associated with time-keeping in cinema. For example, the words “part one” appear multiple times in large typescript, impeding the viewer from finding any stability among its images and disordered progression of events. Instead, Argument points the viewers toward other anchors in its constantly shifting screen. Terms like “Absence” and “Being a Problem” appear on-screen right before a clip in which a group of delegates discuss their decision to formally recognize Palestine as a state. Moments like these don’t just undermine the West’s monopoly on history and memory, they also frame the world’s preoccupation with facts as something comedic. This is most apparent when the directors place a clip of politicians openly debating the legitimacy of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) on top of a shot of the Israeli ambassador’s empty seat.

Argument moves quickly between anti-Arab images—worn down seraglios in films such as Rudolph Valentino’s The Sheik (1921) and Elvis Presley's Harum Scarum (1965) to the dehumanization of Arabs in more modern American epics like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). Voice-overs and texts in the film usually discuss the legitimacy of the Palestinian State and the social death woven into that very debate. But Argument does not just show full-throttled racist found footage, it makes a pointed critique of a tilted political system that is designed to thwart any form of Palestinian resistance.

Introduction to the End of an Argument screens tonight, September 7, at Anthology Film Archives as part of the series “My Homeland is not a Suitcase: Annemarie Jacir, Emily Jacir, and Dar Jacir for Art and Research. Curator Emily Jacir will be in attendance for a post-screening conversation.