The first time I saw the sign must have been the first time I ever went to Film Forum. Having had a look at the PDFs of old print calendars hidden deep in the recesses of Film Forum’s website I believe I can date this to January of 2003, when I was a freshman at NYU, for the Rialto Pictures re-release of the restored, uncut Le Cercle Rouge (1970), though it may not have been until that fall, when I was living in a dorm in the West Village and biked over some weeknight not long after Halloween to catch the late show of Eyes Without a Face (1960).

By sophomore year I was a Cinema Studies major and a projectionist for “Sight and Sound: Film,” the mandatory 16mm production course at Tisch’s film school. I would read the Village Voice in the booth while the reels were whirring through the projector, listening for the crunching and flapping sounds that meant a haphazardly applied piece of splice tape had detached from the celluloid. The Voice critics in those days had the freedom and the column inches to treat every weeklong revival as an event, which to me, a 19-year-old from Maine who had signed up for an Ozu elective because I got Tokyo Story (1953) mixed up with Tokyo Drifter (1966), they were.

The sign was brand new then. You’ve seen it. At the concessions stand, by the trays of baked goods. A yellow rectangle, a bit bigger than a business card, of now slightly battered-looking yellow construction paper with black lettering, in a clear plastic case:

“I love this banana bread!”

-Jacques Derrida, as reported by Time Magazine (Nov 18, 2002)

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Juanita Fama, who has worked at Film Forum concessions since early 2019, told me that that very morning she had seen a father pointing out the sign to his young son, before the Film Forum Jr. screening of Babe (1995). “I was like, What, does the kid know Derrida? People do point it out. People who can’t believe it; they think we're making it up. Mostly when people point it out it’s to confirm. They’re like, ‘Is this true?’ And I'm like, ‘Look it up!’”

Joe Berger, Film Forum’s Theater Operations and Events Manager, confirms that the sign has been “20 years of fodder for discussion at our concession stand. . . . This French philosopher commenting on . . . banana bread. It's ludicrous, but kind of perfect.”

On the one hand, an endorsement from no less a personage than the father of deconstruction highlights Film Forum’s image as a cathedral of high culture and a center of New York intellectual life. Their equivalents of the dancing soda and candy in Dave Fleischer’s “Let’s All Go to the Lobby” (1957) are Jacques Derrida and A. O. Scott of the Times, whose rave review of their popcorn (no butter, kettle-cooked in peanut oil) adorns the machine.

On the other hand, it’s goofy and counterintuitive, the idea of Jacques Derrida, so profoundly skeptical of the ability of language to capture true meaning, giving way to gushing, unguarded enthusiasm as he chows down on banana bread—a larger-than-life icon scaled back down to human size by the base, corporeal fact of food, like Wolfman Jack eating a popsicle in American Graffiti (1973).

When Film Forum reopened in spring of 2021, after more than a year of Covid-enforced closure, the sign was missing, sending a ripple of panic through the staff; Fama, fortunately, found it behind the fridge. So little in New York City is the same as it was 20 years ago; Film Forum’s banana bread sign is an aide-mémoire for many people, for many reasons. To celebrate its 20th birthday, I spoke to a number of people for whom the sign has significance. We spoke about Derrida, his philosophy, and his hair; about the making and marketing of the 2002 documentary Derrida, a Film Forum premiere; about Film Forum, its culture and concessions; about the state of cinema and the media at the turn of the 21st century; about the changing face of downtown Manhattan—and we spoke about the haunting (and, to my mind, unresolved) ambiguity as to what Jacques Derrida really said about Film Forum’s banana bread, and what he meant.

Jacques Derrida sampled Film Forum’s banana bread in the office of Film Forum Director Karen Cooper, as Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering’s documentary Derrida played to a packed house downstairs on the first night of its Film Forum theatrical run—Wednesday, October 23, 2002.

October in those days was “Derrida month” at NYU, according to Avital Ronell, University Professor of German and Comparative Literature, who co-taught seminars with him when he came to the university as a Global Distinguished Professor. “He always pulled in a great crowd—they were hanging on the rafters. People would drive from as far as Ohio and Virginia to come to his seminars.” The implications of his radical work are, she feels, still being teased out across academia in fields as disparate as gender studies, critical race theory, and legal studies. “It mobilized a lot of energy, a lot of excitement. It was very breakthrough each time, when he would bring his work. Professors and students rallied around it, so he was a cult figure, which is never a totally good thing. It invites a lot of put-downs and simplifications, sometimes egregious simplifications. But it was very exciting for NYU to host Derrida. It really put us on the map in a certain way, that we were cutting-edge, more seriously attuned to the demands of the times than that other school uptown.”

When I irreverently suggest to Ronell that this makes Derrida something like a “highbrow Felicity,” she enthusiastically assents. For better or worse, his presence burnished NYU’s profile as a leading global research university and education brand, as did Keri Russell’s turn as the eponymous heroine and NYU student on The WB. She graduated in 2002, a few months before Derrida screened and I matriculated, during NYU’s rise into the Top 10 of both The Princeton Review’s “dream school” rankings and the list of the largest private property owners in New York City.

I recall Derrida being a galvanic, somewhat controversial figure on campus when Derrida opened, in the time between 9/11 and Bush’s invasion of Iraq—a reactionary cultural moment during which dispassionate critical inquiry was often tarred as effete, traitorous elitism. Derrida wasn’t postmodern, Ronell says, “but the detractors would often tag him with that to belittle the serious philosophical interrogation he conducted of basic premises.”

I specifically remember a column in the Washington Square News, NYU’s student newspaper, decrying his presence and influence at the University and taking aim at deconstruction’s decadent refusal of epistemological and, I suppose, political certainties; I can’t be 100% certain, but it seems likely that the author brought up Derrida’s affiliation with fellow deconstructionist and Nazi collaborator Paul de Man. (Derrida was, of course, a Jew; Ronell recalls that he was acutely aware that his mother disapproved of his traveling on Yom Kippur.) Call it a Bush-era throwback to the culture wars of the 1980s. “He is a controversial [figure],” Ronell says: “It's like having Nietzsche show up. So yes, there's a lot of excitement, noise, misunderstanding. What's remarkable is that such a difficult and serious philosopher attracted so many young and other people who were trying to grapple with his work. He had the prestige in Paris already of Aristotle walking among them.”

“Oh my god, if only we had a movie of Wittgenstein,” is how Kirsten Johnson describes the excitement around the making of Derrida. Amy Ziering, now a prominent nonfiction filmmaker, had studied with Derrida in the early 1980s and was resolved to make a movie, eventually linking up with her more experienced co-director Kirby Dick. Johnson was then a student at La Fémis who “had never really shot an actual documentary before.”

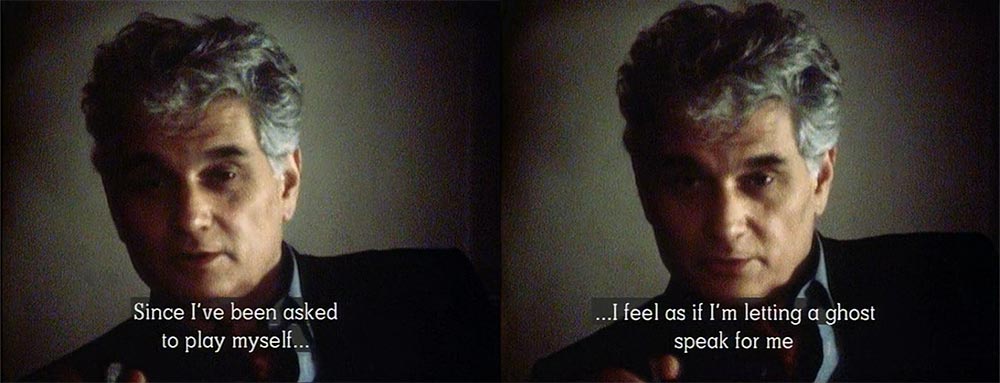

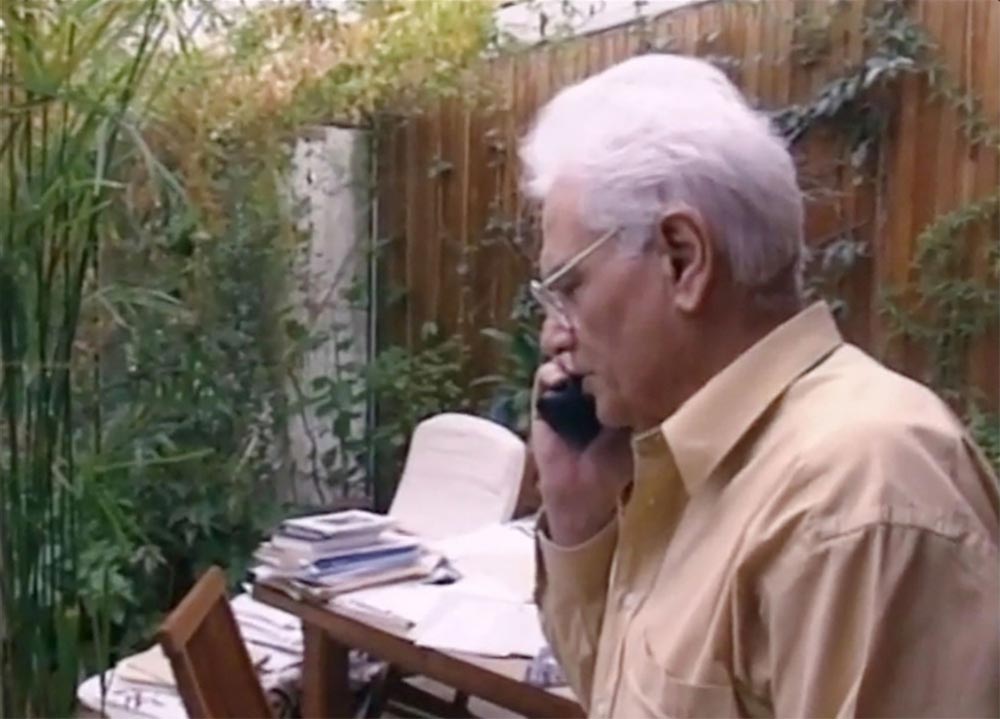

Derrida did not have much to do with the movies. He plays himself in Ken McMullen’s unclassifiable 1983 feature Ghost Dance, extemporizing to Pascale Ogier about the ghostly traces of the self disseminated across the telecommunications spectrum by new media in a five-minute cameo, and he had been the subject of Derrida’s Elsewhere (1999), an essayistic portrait by the poet Safaa Fathy. According to Ronell, Marguerite Duras intended to use him in a film planned in part around his ideas, but the two were both too booked up through the ’80s and ’90s to ever set aside the time. While other celebrity philosophers like Deleuze and Žižek engaged with the cinema head-on, Ronell says, Derrida was conscious of ignoring it, though he certainly went to the movies: she recalls seeing a Godard film with him. “Derrida thought that Godard—I hope he forgives me, both of them forgive me—was too didactic, like a Brecht play, and too insistent on trying to educate us.”

The philosopher was a reluctant, challenging subject. Johnson recalls him being “so intimidating, and so . . . prodigious.” On one of her first days filming him, the production set up for an interview in Derrida’s maze-like home library. Just before shooting, an atmosphere of reverent silence and nervous anticipation was broken by Derrida’s admonishment. “‘You have done exactly what I told you not to do.’ What he had asked me to do: he literally had asked me to only film him in profile. And I said, ‘Sir, I've set you up completely in profile.’ And he said, ‘I meant the left side.’”

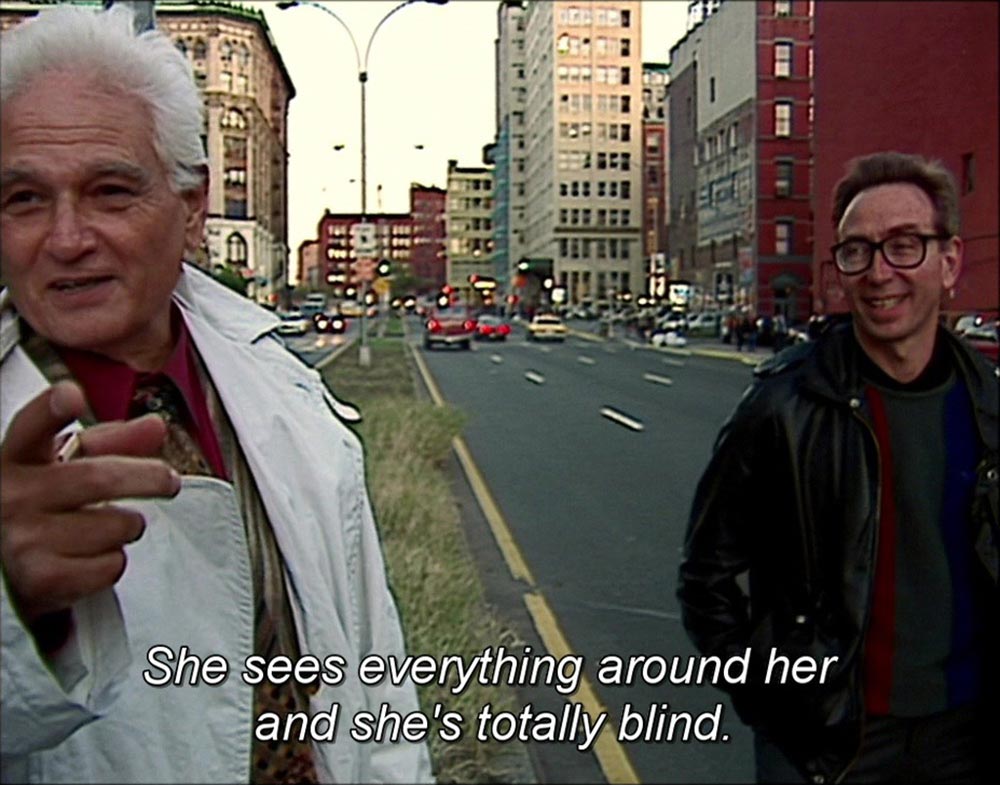

Derrida was shot across much of the 1990s on PAL Beta, NTSC Beta, DVCAM, and miniDV, an early example of the wave of digital nonfiction filmmaking that would democratize access, bring filmmakers closer to subjects—including famous ones—and enable an archival turn. Unsurprisingly, Derrida was skeptical that any essential truths would be revealed.

“‘Can you imagine if we could have seen Wittgenstein eating breakfast?’” Johnson remembers someone posing such a question, or something like it, to Derrida. “That idea was, that would be so meaningful to all of us. . . . And he was like, ‘No, that wouldn’t. It's his thought that is meaningful.’ Everything we proposed, to film him driving in his car or eating in his kitchen or being in his house or going to the barber was like, ‘Whoa! To see this person doing this.’ Which is so banal now. And yet I do believe in thoughtful observation: You can see things that are evidence, or give clues to the inner life, on a very complex level. I do think that it has a lot to do with who's the cameraperson searching.”

In the film, Derrida describes a philosopher’s biography as “pure anecdote.” In contrast to many of the stage-managed, fan-service digital documentaries that followed, and in deference to the content of their subject’s body of work, Johnson and the directors were self-reflexive about their portrait—perhaps to a fault. “I remember us talking about like: ‘We’ll only film him in reflection.’ I made some terrible errors in judgment doing that. For example—I don't know what I was thinking—there was this scene where I was like, ‘We should totally blow out the image so that it’s barely there.’ But I forgot to calculate for his white hair; if you blow out the image he’s going to look bald.”

Johnson compares Derrida to the Madonna of Truth or Dare (1991), a subject from early in the personal-camera revolution who was similarly “hyper-aware of what the camera might do.” He was conscious that the camera was not a true reflection of his self; as he later told Artforum, watching the film he discovered “some truth in it—not the truth that I see myself in the mirror, but a truth as experienced and seen by others. So from that point of view it was a test and a psychoanalytic experiment, working on my own image and trying to see myself the way others see me.”

This was an experiment he entered into with much reluctance, Johnson remembers. For decades Derrida sought not to contaminate his writing with traces of his photograph or biography—“He mistrusted [us]. I do think he was incredibly vain, and felt good about the image he projected, but he thought of that image of him as a reduction of him and his thinking. And one of the big things between us was that he also said to me, ‘No matter how long you film, you will never be able to capture the love between me and my wife.’ . . . She came to one of his lectures, and they'd come walking out of the building together . . . and when they think they're gone from being seen by the camera, I zoom in and I catch this moment of her hand touching his back. It's like through three levels of fence and you can barely see it because it's so grainy, but in that moment I was like, I got it.”

Johnson credits Derrida with giving her “all the questions I have been struggling with, playing with, engaging with, ever since. He really problematized for me what it means to film people. And the dynamic between the two of us was so active, that from then forward I was like, Oh, it’s a relationship, between me and the person I'm filming and the camera. That's what it is.”

All Johnson’s thinking about intimacy, access, reality, and truth is crystalized, for her, in another moment with food. She recalls a day spent alone with him in his house—he was getting ready for a trip, fed up with the crew. “It was always this huge negotiation to arrange a filming day, and he said, ‘I can't have all of you here; maybe, if Kirsten stays, and doesn’t say a word, then that’ll work.’ So Amy left, the rest of the crew left, and I stayed alone in the house with him. I truly credit that day to be my breakthrough as a cameraperson. I was so invested in trying to impress him and be worthy of him intellectually—and he imposed this rule of, I could not speak. Up until then I had thought that intellect was only expressed through speaking. And so I just shut up, and started filming him, finding these moments.

“At a certain point, he got hungry and we sat down in the kitchen. He didn’t miss anything—I remember him clocking me filming the inside of his refrigerator. I could feel him, he was always tracking: ‘What does this look like? Does this work with the image of me?’ I do remember him very tenderly buttering a toasted baguette . . . it was someone who loved to eat. It wasn’t the image he wanted in the world, it was too human, it was too intimate, and it was too close. I was too close. But for me, it was this spectacular day. Most of the footage you see of him in the house, putting the caps back on his pens and all of that, is from that day.”

Derrida’s unease and resistance informs the dynamic in the film itself, which implicitly takes up the old Chronicle of a Summer (1961) discourse about cinema vérité, filtered through Derrida’s thoughts on the contingency of meaning; interviews and voice-over readings from his work offer his thoughts on the slipperiness of language, the invisible and unspeakable in private and public life, and the unknowable Other. Both in interviews with Ziering—“Before responding to this question, I want to make a preliminary remark on the completely artificial character of this situation”—and in interactions with others, he frequently displays annoyance at being treated as a dial-a-quote oracle. People ask him impossible questions, expecting him to be brilliant, and he answers, after a heavy sigh, with prickly, extemporized paragraphs, dragged kicking and screaming into the role of public intellectual and dispenser of sound bites on love, motherhood, irony, and Seinfeld. “I emerged […] through my resistance,” he told Artforum.

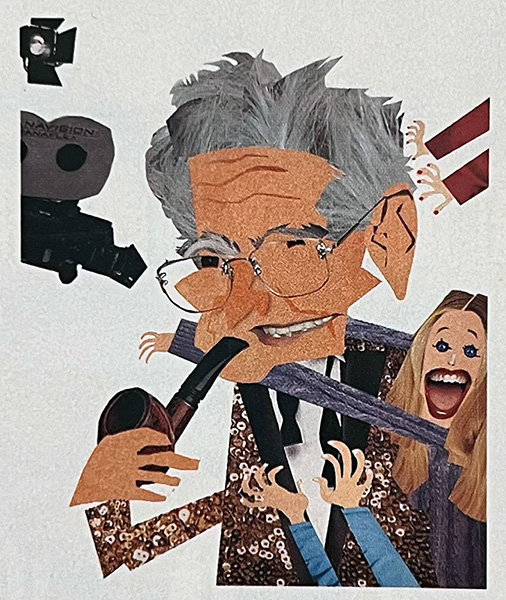

Derrida did not participate much in the promotion of the documentary, recalls Mike Maggiore, now Film Forum’s Artistic Director, who pulled his old files and 2002 day planner to refresh his recollections in anticipation of our interview. The philosopher submitted to a surprisingly accessible Q&A in LA Weekly and the feature in Artforum (by Rhonda Lieberman, who led her piece by calling Derrida “the Madonna of thought” and complimenting his hair). “However,” Maggiore tells me, “I have a note that ‘he has declined all further interviews for this film.’”

Interest from Joel Stein of Time was a big deal for Film Forum, and the subject was a big deal for Stein, who tells me: “I'd had enough experience interviewing people that I knew there’s different types of celebrities to interview. There’s people who are just really famous, and that’s interesting—sometimes; there’s people who meant something to you as a child, and that’s a whole different level of interesting; but then every so often there’d be someone who I thought would be historically important, and my brain feels that when I’m around them: Hugh Hefner, Martina Navratilova, people like that. So I was like, Derrida, that's crazy! [. . .] He definitely had a lot of presence. And it was a little bit of old-school tough-guy presence.”

The screening and Q&A was sold-out, Maggiore recalls, with a standby line; he had been warned to expect a heavy turnout from acolytes informally known as the “Derridettes.” Stein had been told that the great man was not doing interviews; he was, however, invited up to Karen Cooper’s office, which was then used as the green room, for an audience with Derrida, with the expectation that it might, or might not, yield a piece. The encounter may not have been quite the ambush Stein described in his published piece, though it’s likely that their conversation expanded beyond the scope of whatever access, if any, Derrida had initially been persuaded to acquiesce to. “My interest is mostly meeting Jacques Derrida; the story is definitely secondary. So of course I’m going to come and do that. I’m not allowed, journalistically, to lie about who I am, so I did tell him I was a reporter for Time, and he immediately was like, ‘I’m not doing interviews.’ I'm like, ‘Nope! Just hanging out.’ He's like, ‘OK, you can hang out.’”

Stein joined Time in 1997, while still in his twenties. We had a subscription when I was growing up; I remember him as the geeky Gen X-er getting his quips in amidst the logy centrism. A self-described “middlebrow humor columnist,” Stein had read Derrida at Stanford, and “thought it was super cool. Big fan of Derrida. . . . And of course, he also is personally cool, and I was aware of that.”

Stein felt that being poured through the channels of modern celebrity journalism was a diminishment of the almost mythic stature the writer had achieved on the page—“Remember when Cormac McCarthy sat down with Oprah?”—but also admired his scrupulousness in refusing to compromise his thought by giving shallow answers to even the stupidest question. Stein credits Derrida’s example with warning him off the temptations of punditry: “He was tired of people not understanding what he was up to. In my own little way, I’ve adopted this. I’ll be on some TV show or radio show, and someone will ask me, ‘What's going to happen with the election?’ or something. Or, ‘What's going to happen next with some technology?’ As a human being, you want to engage in conversation, and you want to answer their question, but prediction in general is idiocy, and oftentimes people are asking me things out of my depth. . . . So I’ve taken to doing what Derrida does, and saying, basically, ‘I can't answer that question, that question is unanswerable, that’s not a good question.’”

Derrida had established a teasing repartee with the filmmakers assembling his image. Johnson reflects, “When we say ‘vain,’ it’s a thin term, someone who doesn't have depth; I would give him credit for a different kind of vanity, a profound awareness of what it is to be a unique human, this awareness that you are in a body and that you are perceived from the outside by people.” Amy Ziering told IndieWire in 2002 that Derrida would watch raw footage and say, “‘Can you keep that in?’ but it was more as schtick, than theoretical conceit. He would say he like[d] the way he looked in one scene, or that his hair looked good, keep it in.”

With Stein, he established a similar relation as joking-but-not-joking co-author, fueled by a similar blend of vanity and self-awareness, and centered around the same object. Stein recalls the two of them “sitting somewhat quietly in this green room and just . . . sort of talking? I think I had just met Brian Grazer? No, maybe not. So I was like, ‘How do you get your hair like that?’ Right? Because Derrida has that Samuel Beckett hair. He was a very handsome man. Even at that age—maybe even especially at that age—in that . . . intimidating, badass way. He was like, ‘My hair? You want to talk about my hair?’ And I was like, ‘I totally want to talk about your hair. You have amazing hair!’ And he was like, ‘Oh. Well, you can write that. You can write that I don't put any product in there.’”

This is an image, a reduction, an anecdote, albeit one Derrida could live with. As Stein “attempted to interview Jacques Derrida,” Maggiore says, he had offered to bring up food from concessions; Derrida declined—“‘Non non non, I don't need anything’”—but changed his mind when he saw someone else eating. “His eyes lit up.”

As Stein wrote in Time, Derrida took a bite of the banana bread. He loved it, he said. “You can write that.”

He told Stein that he would answer questions about “facts.” What can we say to be true? “I would not deny that there is some truth of myself in the film,” Derrida told Artforum. “It’s not the truth. It’s not the total truth. But who can claim that any access to the total truth of oneself is possible? [. . .] There are only interpretations.” In the film, Derrida physically winces when asked to speak on the subject of love; Maggiore recalls a moment from the post-screening Q&A (recorded for a special feature on the Zeitgeist DVD) in which Derrida is asked what he thinks of the film—he can’t, he says, seriously say that he loves the film. That would be impossible. But, Maggiore smiles, he did say he loved Film Forum’s banana bread.

The food we consume at movie theaters is part and parcel of the culture we consume there, argues James Lyons in “What About the Popcorn? Food and the Film-Watching Experience,” an argument that holds true from the Second World War—when popcorn emerged as an alternative to heavily rationed sugar and chocolate, and followed American servicemen around the world as an emerging metaphor for the homogeneity and populism of Hollywood blockbusters—to the present day of boozy milkshakes at an A24 brunch.

According to Juanita Fama, the banana bread is an enduringly popular concession item at Film Forum, where it stands out from typical multiplex fare. Since Film Forum relocated from Watts Street to its current location on Houston Street, in 1990, its vibe has been “the coffeeshop experience,” according to Berger, who likes the arthouse café ethos—a little caffeine buzz to focus the mind during the film, and fuel conversation afterwards.

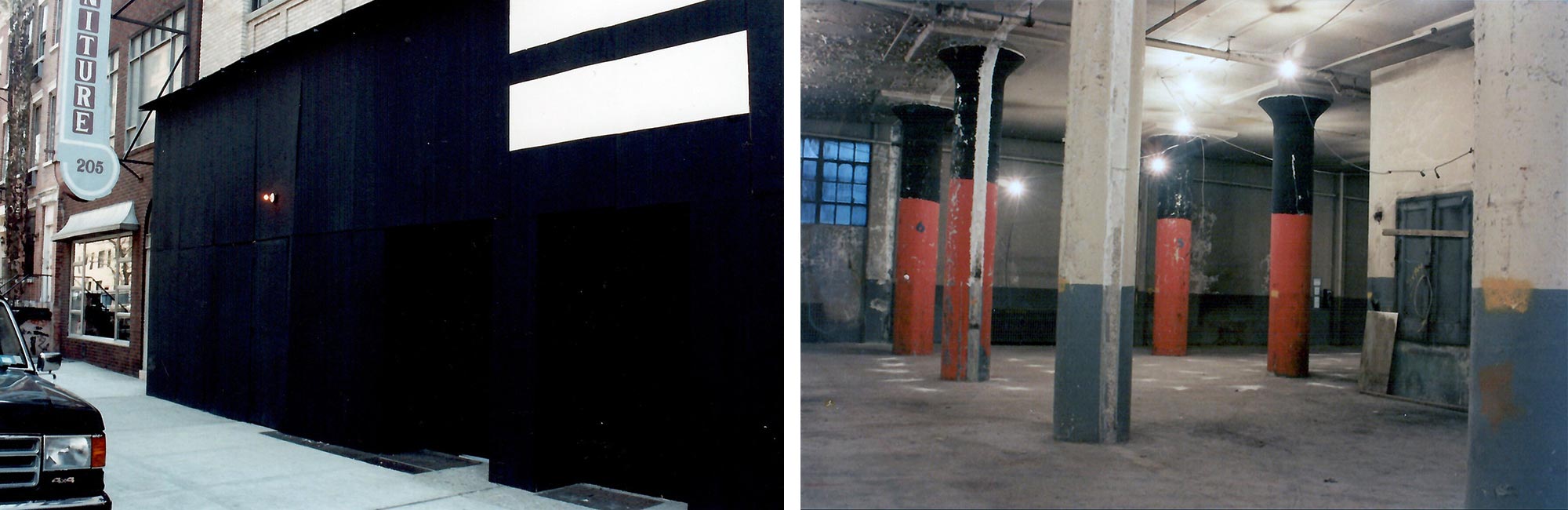

The specialty-coffee boom of the 1990s, which fueled international phenomena such as the kudzu-like expansion of Starbucks, and “New York” phenomena like a sitcom set around the punnily-named Central Perk, coincided with a transitional period in SoHo at the end of the downtown ’80s. Receding crime rates and real estate investment reshaped Lower Manhattan’s image into a more accessible cosmopolis, or less charitably, a bohemian LARPing ground attractive to the children of upper-middle-class suburbia, such as myself. This is the context in which the arthouse-as-coffeehouse model emerged. Angelika opened on Houston in 1989, a year before Film Forum and a few blocks east, featuring, as the Times noted, “an espresso bar and cafe catered by Dean & DeLuca”—the namesake of the coffee shop where Felicity slung espresso drinks through her college years.

Since the 1990s, Film Forum has sourced its banana bread from the same Brooklyn bakery: formerly a commercial kitchen called Cheryl Kleinman Cakes, the business was sold in the 2010s and became the retail storefront Betty Bakery, but the banana bread recipe remains unchanged. So does much else at Film Forum concessions—on the phone with me, Berger described the occasional switching-up in chocolate offerings as “revolutionary.” Though, in a sign of the times, Film Forum recently received a beer and wine license and now serves “one beer, one white, one red.”

When Derrida complimented the banana bread, Maggiore recalls, “we all thought it was funny. I would never have guessed that Joel would put it in his piece, but it may have been because Derrida was not as forthcoming with other thoughts during that interview. […] I’m pretty sure that when Karen and I saw that piece, that we both looked at each other and thought, ‘That's fair game.’ We think the audience will be interested to know that the New York Times thinks we have the best movie theater popcorn, and those who know who Jacques Derrida is, was, would have found it interesting, slightly amusing, that we would be hyping the banana bread with his name. But he did—I saw his eyes light up when he bit into that banana bread. It was an electric moment.”

The sign was produced “right away,” in Berger’s memory, and immediately became part of Film Forum lore, an inside joke for two decades’ worth of employees that has taken on many forms over the years. When I spoke to her last month, Fama told me that there’s long been talk of merchandising; indeed, it seems the theater has now decided to follow through, printing up a limited run of t-shirts displaying a reproduction of the sign now for sale online and at the concessions stand.

Continuity is a watchword at Film Forum, where the columns will always be the same shade of red, and where Karen Cooper—very hands-on with every aspect of Film Forum, including concessions—has been Director since 1972 and Bruce Goldstein the lead repertory programmer since 1987. Berger started at Film Forum in 1999, first as a concessionaire, later as a manager. Every day we deposit a little residue of ourselves in the places we pass through and when the deposits become noticeable enough we call them the past. Many of Berger’s employees were not yet born when he started working at Film Forum, or when I started going there. “If you stick around,” he reflected to me, you end up having a voice in the history.” (I can’t think of a better place for this piece to run than in a record of our days measured out in repertory film screenings.)

“The gift (dōron) of Mnemosyne, [the goddess of memory and the mother of the muses], Socrates insists, is like the wax in which all that we wish to guard in our memory is engraved in relief so that it may leave a mark, like that of rings, bands, or seals,” Derrida once wrote. “We preserve our memory and our knowledge of them; we can then speak of them, and do them justice, as long as their image (eidōlon) remains legible.”

Kirsten Johnson lived for many years in the Village, not far from Film Forum. “When I was a younger person in New York,” she says, around the late 1990s, Film Forum had an outsized, aspirational stature: “I was like, Could I dare to hope that someday one of my films would play at Film Forum?” (The first time I saw a review of mine blown up in the lobby there was one of the best days of my life.) Now, she goes with her family, taking her kids to Film Forum Jr., seeing many of the same faces taking tickets and at concessions (where she usually gets a molasses cookie), realizing “they have watched our children grow up.” And every time, she sees a yellow card trumpeting what someone said while promoting the film that launched her career. “On a certain level it’s a fabulous tombstone,” she says. It reminds her of all the chairs in Film Forum’s various theaters emblazoned with the plaques memorializing former patrons. Since making Dick Johnson Is Dead (2020), about her aging and ailing father, she’s given a lot of thought to how to memorialize a person. Ira Sachs, with whom she co-parents, has said he will be purchasing a “Long Live Dick Johnson” plaque for one of the seats at Film Forum. She loves the idea of a memorial “that evokes pleasure, humor; evokes the person and a different time and place. Derrida is alive for me every time I see the sign, and it also reminds me that he’s dead.”

Derrida posited writing as the ultimate form of pharmakon, an unstable sign containing multiple opposing meanings. Fittingly, then, for this Narcissus whose utterances were taken up by so many adoring Echoes, there are contrasting accounts of what he actually said about Film Forum’s banana bread, and what the sign means.

Over the past 20 years, countless New York repertory filmgoers with obscurantist inclinations will surely have looked up the quote and noticed a curious thing: The sign says “I love this banana bread,” but the actual quote, as recounted in the pages of Time, is different: “After he was offered banana bread,” Stein wrote, “and tried it for the first time, he loved it so much that he pointed to me and said, ‘You can write that. I love banana bread.’”

Should the sign have had brackets all these years? “I love [this] banana bread”? Maggiore is adamant that the sign is correct; he and Karen Cooper, whose pride in hospitality is one reason the sign exists, were surprised to read the quote in Time, since “We were both in the room with Derrida, we saw him take a bite, brighten up, point to the bread”—not at Stein—“and (we’re quite certain) say ‘I love this banana bread.’ It was the most effusive thing he said.”

Stein, whose eye for the telling human detail is the other reason the sign exists, is equally certain about the quote, and its context. “So he has the banana bread and he's like, ‘What is this?’ And someone's like, ‘It’s banana bread.’ And he's like, ‘It's what?’ Apparently that's not a big hit in France. And he’s like, ‘This is great. You can write that down too.’ So. This is the qualification I want to make for that sign at Film Forum. It seems to imply that Jacques Derrida is some kind of expert in banana bread and thinks this is the best banana bread ever. But in reality, this is the only banana bread he’s ever had, and he's just saying he likes banana bread as a product.” Stein has been eager to speak to me about this; he’s aware of the existence of the banana bread sign, and has deep qualms about what it implies about Derrida, and his discernment as a judge of banana bread. When I tell him about the “this,” he gasps. I had told Stein that I remembered his writing from when I was thirteen years old; it is possible now that he is doing a bit of schtick for my benefit, slipping into the same flip, neurotic cadences of his old columns: “I’m passionate about this subject!”

So. Perhaps the good people of Film Forum heard what they wanted to hear, or perhaps they worked a little movie-publicity pull-quote magic on a nearly-there quote—it wouldn’t be the first time, as every critic knows—and then stuck to their story until they believed it. Print the legend, right? Perhaps Stein mistranscribed the quote, or misread the room. Perhaps both are a little right, a little wrong. I’m imagining Jacques Derrida biting the banana bread and saying “I love this . . . banana bread,” the pause eliding a French-accented “how do you say.” Talk about a rupture between meaning and the voice!

No one I spoke to had any doubt that Jacques Derrida loved Film Forum’s banana bread. It is wonderful banana bread: moist without being heavy, sweet without being cloying. Press your finger into the crumb and it springs back like an air mattress slowly inflating.

In any event, the sign endures: the wax in which all that we wish to guard in our memory has been engraved in relief. Kirsten Johnson was at Film Forum that night as well—she filmed the post-screening Q&A. She wasn’t in Karen Cooper’s office and can’t resolve the conflicting memories, but, she says, “Whatever the case, I'm sure his language was precise.” Derrida said what he meant, and it's up to us to interpret it. He’s gone, and we’re here.

Thanks to Andrea Torres, Beatrice Loayza, Harris Dew, Scott Macaulay, and Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer.