Jerry Schatzberg’s second film, The Panic in Needle Park, came out in the summer of 1971 and was immediately both beloved and reviled by audiences and critics. The 20th Century Fox release was a kind of dividing point in the New Hollywood of the time, embraced for the immediacy and truth of its portrait of junkies living in the margins of New York City, congregating at 72nd Street and Broadway during a heroin shortage in the city. At the same time, some prominent critics in magazines like The New Republic pronounced the film “rotten” and boring, two things no viewer would think of it today.

However it was received, there is no doubt that it made Al Pacino a star. His portrayal of Bobby, an eight-time loser, petty thief, and semi-homeless addict, introduced him to the world. Kitty Winn, as Helen, a fledgling artist from Indiana who rejects her upbringing to become Bobby’s girlfriend, a fellow user, and a prostitute, was just as revelatory as Pacino, but her career did not take off the same way.

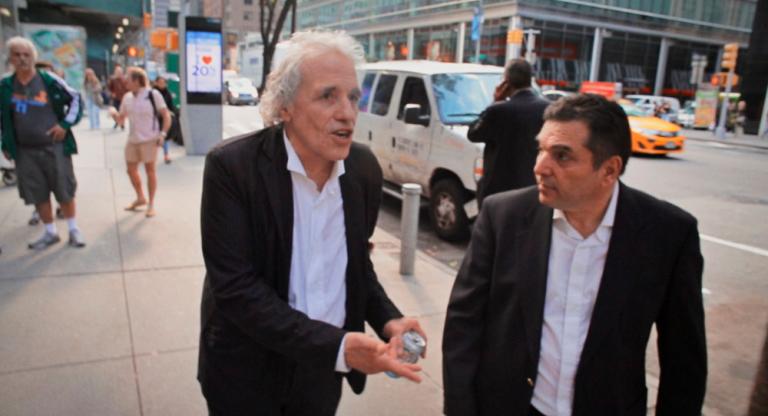

Schatzberg, born in 1927, was a prominent fashion photographer who had made one previous film, 1970’s Puzzle of a Downfall Child, with his then-girlfriend Faye Dunaway in the lead role. Known also as a photographer for Bob Dylan album covers, Schatzberg seems to have gone into directing only reluctantly, which perhaps contributed to his originality and success. He never embraced the rules of conventional filmmaking, ignoring them in pursuit of a higher truth. To mark the film’s 50th anniversary, Film Forum is showing The Panic in Needle Park tonight in a digital restoration [alas, sold out –ed]. I spoke with Jerry Schatzberg by phone. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

A. S. Hamrah: Hey, Jerry. How are you? Congratulations on the 50th anniversary of The Panic in Needle Park.

Jerry Schatzberg: Thank you. I'm only 35, so...

ASH: It's amazing how that works. I rewatched The Panic in Needle Park last night. It’s such a remarkable film. There are three things that really make it so different. One is the story, which is still so potent and shocking. The other is the acting, and then the New York City locations. Watching it now, everyone and every place is so vivid and grimy and great. Everything is so alive, and it seems so effortless.

JS: Well, half of the actors were recommended by Al [Pacino], so how can you go bad that way? These were his pals. These are the guys he used to hang out with. Anytime he could, he'd recommend one of his buddies for a part.

ASH: Pacino is so amazing in this film. It must have been such a revelation for people to see him at the time.

JS: It's in that period that he did The Godfather (1972). Francis [Ford Coppola] wanted him because Francis had seen him on the stage the same way I had seen him on the stage, and was impressed also. And, I don't remember who did it, was it Fox who did The Godfather? I don't remember, but they didn't want him. Oh no, it was Paramount. And they turned him down. Four times he screen-tested and they turned him down. But Francis knew that I was shooting Panic and he asked if he could get some footage. And I had put together a twenty-minute piece, and I sent it to him, and that's when Al got that part.

ASH: Another actor that really impressed me this time was Richard Bright, as Pacino’s brother Hank. He has this truly menacing quality that just seems so real on screen. And his voice is so New York and just sounds evil, but also right and normal for the character.

JS: Yeah. He was a good friend of ours and he lived near me. He lived about a block away from me and he was married to the nurse [Ruth Alda] at the beginning of the film. And I told these guys that—I guess there were a number of them that had been addicts—and I said, “I don't want any shooting up. If I find out, I'm liable to just take all your footage and throw it away and get somebody else.” Because I just thought it would become a problem. And I found out after the shoot, he was the only guy that was on drugs in the film, Richard was. He was able to handle it, but I just didn't want to get into a thing where I was dealing with drug addicts. It was bad enough dealing with actors.

ASH: The shooting up in the film seems so real. How did you achieve that? There are all those close-ups with the actors themselves, it’s not faked.

JS: We just shot up but we didn't shoot up drugs. We just shot up saltwater and things like that, that wouldn't harm them. We talked to a doctor and they said it was okay. Kitty [Winn] was a newcomer, but we had her shoot up also. But we just made sure we were protecting them in whatever way we could. I didn't know how to shoot this thing without showing that. I thought that was so horrendous. That and the dog. Everybody, every time they see the dog: “Oh!”

ASH: That's such a terrible thing, a low point for the couple in the film. They go to the men's room together on the ferry to shoot up after they buy a dog on Staten Island.

JS: All that attitude, all that behavior, that stuff is real. That's the way they are, how they lived.

ASH: The film is shot by this cinematographer, Adam Holender, whose work I don’t know very well, except he shot Midnight Cowboy two years before The Panic in Needle Park.

JS: He did four films for me. He was in school with [Roman] Polanski and I got him. I knew that he was here [in New York]. I was friendly with Polanski, and I asked Roman about him. And he said, “He's good guy.”

ASH: His cinematography is so perfect for your film. Why did he not shoot more after your stuff?

JS: I think he did. You may not know them and the films may not be that good, but no, if you look him up, he's done a number of films.

ASH: He worked for Wayne Wang and Paul Auster in the '90s, I know.

JS: Yeah. That sounds familiar. What films did he do?

ASH: He did Blue in the Face and Smoke (both 1995), which are great New York films, too—especially Blue in the Face, I think.

JS: For me he did The Seduction of Joe Tynan (1979), he did Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970) right before The Panic in Needle Park. I liked his work. And I wanted somebody that I could depend on as a cameraman, because my problem before my first film was how would I be able to behave with the actors? I'd never taken a course in acting. I don't know what they're looking for, or what they want. It was not what I was into and I had started later in life. I did my first film when I was 40. And so I wanted somebody that I could depend on, on the camera. If I said, “Adam, we want this and this and this and this,” I didn't have to sit with him for an hour to explain why and all that. He'd just do it, so well.

ASH: You had made Puzzle of a Downfall Child already, but then how did the script for The Panic in Needle Park by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne come to you?

JS: They sent it to me because I was friendly with Dominick Dunne, who was the producer of the film. He was the brother of John Dunne and they had this script, and I don't know whether they had seen the screening of Puzzle, but they sent me the script and I turned it down.

ASH: You turned it down?

JS: I turned it down because the lab had scratched the last six minutes of my negative on Puzzle. I was very upset about that. I was new at this, and these kind of accidents were dramas to me, and to anybody who's new in the business. Luckily I made a copy negative, but the quality of the last six minutes was different than the rest of the film. And then when digital came along, we were able to make them the same. Digital helped us equalize the quality. And those things you have to learn, you have to put up with them. Most of us were learning because even the actors were fairly new to it.

ASH: Why did this lab accident make you not want to direct another film?

JS: Because I was just upset with what they did to my film. In my mind, I was going to do one film. And when I'd look at the end of the film I'd see the difference in quality, because I'm also a photographer, so I knew. It really upset me and it wasn't my fault, it was the lab's fault. Somebody just screwed up. Then when I read their script, and I had a lot of friends who were into drugs, and I didn't really know if I wanted to join that group of people. When I read the Life magazine article their script was based on, it was really a downer. And I had to think it out.

ASH: The acting seems so real and natural, I was wondering how much of the screenplay was changed by the actors when you were shooting it, or did you stick closely to what Didion and Dunne had written?

JS: No, I didn’t. I learned a lot fast. I had a lot of time to spend with Kitty and Al before we shot, because they weren't doing anything. So we just hung out together as much as we could. My whole thing in my art or whatever it is, is to go for the truth. I'm always looking for something honest, even in my stills. If you look at my stills, even when I'm doing fashion, I'm looking for something that makes it a little more real and a little more honest. And that's what I would count on, and here I had a whole world out there that I could investigate and use. One of my favorite films that I loved was The Battle of Algiers (1966). Do you know that?

ASH: I do.

JS: That was so real. But when I look at it now, I'm not sure it's as real as I thought it was back then. But for me at the time, that was real. The only drug film I knew at that time was The Man with the Golden Arm (1955). And it was so Hollywood and so corny in so many ways that I couldn't relate to. But Battle of Algiers, I felt, was a real happening. And Adam and I sat and watched it a number of times to see the honesty in it.

ASH: The Hollywood film that The Panic in Needle Park reminded me of a little bit was The Days of Wine and Roses (1962).

JS: That's because of the alcoholism, and Jack Lemmon was wonderful. A good actor is a good actor. And he was right for that. I probably wouldn’t have had a part for him in my film!

ASH: It also kind of reminded me a little bit of Breathless (1960), watching it this time, because the scene near the end is like the scene that ends Breathless.

JS: I didn’t get the title.

ASH: Oh. Breathless.

JS: Breathless? You say Breathless?

ASH: Yeah. Breathless.

JS: Breathless? With John-Paul Belmondo?

ASH: Right. The end—

JS: He died, I think this year. And I had met him a couple times in Lyon, when he was getting older.

ASH: So your work with the actors did end up changing a lot of the screenplay, the dialogue?

JS: Well, that's the way I work. If an actor says something in the script and it doesn't fit the character that has been created, I never change the meaning of what we're saying, but I may change the words because it doesn't fit the character for me.

ASH: Some of Pacino's lines are so funny and they just seem so spontaneous: “I just flew in from Jersey City”; “This is UHF, you get everything on here”; “I know someone who shot paregoric and shoe polish.”

JS: When I can get it from the actor, it's coming from the characters. They know how to make their character appealing. That's what they do. They create a character, and then you’ve got to stay consistent with it, and people sit in a room and watch it. And they weren't really experienced screenwriters, the Dunnes. They wrote wonderful essays, but they weren't screenwriters. They interviewed Joan Didion once when somebody was doing a documentary on some of my work. The interviewer said, "How did Jerry go for your dialogue?" And she said, "He didn't care for the dialogue, no. He didn't care for any dialogue.” I love that. Because, I think different people see truth in a different way. I looked at Man With the Golden Arm because it was a drug film and my God, it was so corny and Hollywood and that was our big drug film of the time.

ASH: That movie was shot entirely on a soundstage on one big set.

JS: Yeah. That's Hollywood.

ASH: And that was an Otto Preminger film. Wasn't Faye Dunaway under some weird contract with Preminger when you made Puzzle of a Downfall Child?

JS: Faye had a contract with him, a six-picture deal. Because when she did her first film, everybody wanted her and somebody else made deals for her. She had to buy her way out of that contract. But I had nothing to do with that. That was before Puzzle.

ASH: I see. And that was before Needle Park, of course.

JS: Now I don’t know how they will take Needle Park. I hadn't seen it in a while. But things are different now, in people’s lives.

ASH: It’s hard to imagine an audience not responding to The Panic in Needle Park in a positive way. But it’s true that was a different New York. How is New York different now compared to then? Are we going back to that? Or is that something that's completely gone?

JS: Drugs?

ASH: Not just with drugs. The precarity of their lives.

JS: The whole world is different. A different world. All of New York is different. New York is more women being part of it, more Blacks and Hispanics. When we live in it all the time, we don't see it. I'm old enough to have lived through different eras and I think of those things, but I'm sure if I were to make the film today, I would change certain things.

ASH: That part of New York City is such a wealthy enclave now.

JS: Where I shot it—I didn't shoot it actually in Needle Park. Needle Park is where the subway is and I was a block, a block and a half away from that. But I used the buildings around it and I felt it worked there, but today I would involve more women in a different way.

ASH: I’m surprised to hear you say that about this particular film. It's a multiethnic film, really, and women are so prominent in it. That is one reason it holds up so well. It’s still relevant because it’s open to all these people smashed together for this one reason. Kitty Winn’s performance is a tour de force, and it was recognized that way at the time.

JS: Drug addicts are not your normal people. They get pulled in by a boyfriend or by another girlfriend or something. They don't grow up. As time went on, we saw how many kids in school became drug addicts. Not because of my film! Maybe the article in Life magazine at first and it just became much more popular. When people can make money on it, they're going to publicize it to the degree that people can make more money on it.

ASH: It's not exactly a film that makes you want to do heroin, I don't think.

JS: No, not my film. I told you that I feared the whole idea of doing drugs. If you're in school and you go home and your mother says or your father says, "No. You can't do that.” They immediately, fifteen-, sixteen-year-olds, want to rebel against that. And they did.