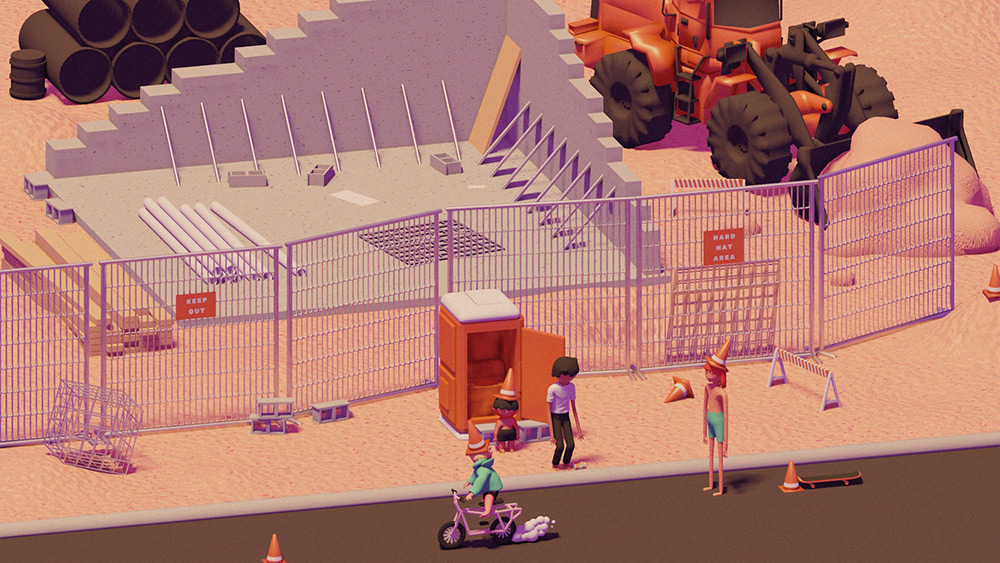

Artist Julian Glander’s first feature, Boys Go to Jupiter, follows a group of Florida teenagers during a languid summer in which they hang out talking about Big Ideas between gig economy shifts and local UFO intrigue. Glander’s animated work, a blend of surreal sweetness and revolting plasticity created with free 3D software Blender, has previously appeared in The New York Times and on Adult Swim. In Jupiter, an impressive cast of cult comedians (Joe Pera, Sarah Sherman, Julio Torres, and Chris Fleming among them) gives voice to Glander’s anxieties about the relentless dehumanization wrought by Silicon Valley overlords looking to simultaneously create new pathways of consumer desire and a new class of cheap labor to undergird the process. The sorbet-colored images themselves work against the dizzying activity of the on-demand internet by offering stationary compositions in which unhurried scenes develop the characters and story free of restless camera movement and neurotic cutting. If you’ve ever caught yourself hypnotized by the visual loop of the “lofi beats to study to” girl and her cat, you’ll find similar relief from the digital onslaught in Glander’s film.

I sat down with Glander recently to discuss the making of the film, Florida, clouds, duck eggs, and nostalgia for bygone eras of the internet. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Patrick Dahl: The strongest reaction I had watching the film was in response to your balancing act between the cuteness of your constructed world and the kind of off-putting, mildly disturbing, and kind of an uncanny quality it has. I think this tug-of-war is present in a lot of animation, but it’s so close to the surface of Boys Go To Jupiter. You have traditionally cute things like animated people who, in your rendering, also look like tumorous sausages and have tons of weird lumps, but then you also have literal shit and vomit that have an endearing, adorable texture. How conscious were you of this balance when putting the film together?

Julian Glander: It was more of an intuitive sensibility thing than a conscious thing. One problem I had was making aliens, donuts, and worms look special, so the humans had to be reigned in a little bit. I think if I was doing a movie about just people, it would probably have gone more into that Corporate Memphis thing. In all my years of working, these are actually the most normal people I’ve ever created. I’ve spent so long with this movie that everything in it feels very normal to me and I'm somewhat defamiliarized to this world now. When I look up from the screen now things just feel desaturated in comparison.

PD: On that note, ahead of this interview I went through your website to get the Glander mindset going. The color palette of your work is remarkably consistent, going back more than a decade. Were you consciously aware that you were developing a signature color scheme?

JG: When I'm in the zone choosing colors, it's very intuitive. In the moment, I’m running my mouse around the color wheel and looking for this, like, I would call it an eye tingle. When something’s right, it’s almost like ASMR. That’s it! One shade off, and it’s completely wrong.

The style itself I think is a response to market forces when I started doing illustration. When I started my career I was posting on Tumblr, and the best thing I could think to do was filling the whole page with the most audacious purple ever in order to keep people scrolling. From there I kind of fell in love with it. The reason it works in the movie is because they are almost like characters from a DoorDash commercial who have their own internal lives, and I’m wondering what they would be doing outside of the bright and bubbly commercial. Also it’s the Florida palette. I mean, I grew up in Land O' Lakes, Florida, where they made Edward Scissorhands, and those houses still exist. That sort of melty-acid-pastel-psycho-blast of Florida is so deep in my memory. I haven’t been back to Florida in so long, which helps let it kind of ferment and get even crazier in my mind.

PD: One of my favorite things that you’ve done is Clouds Moving (2016).

JG: Oh, thank you. That's my favorite for sure.

PD: The description (“One minute of peace and calm on this darn crazy web of ours.”) that accompanies that 1-minute film is an essential part of the work. It’s an announcement of intention and it gets to a need we all have, then and now. The centrality of the description makes me think of the piece not necessarily as just a film, but a digital-native work or online installation or something. Your work has these different forms, and here we are talking about one of the more antiquated things that you could do with your talent and career, and that's make a feature film. You’ve done a lot of work that speaks to the moment we’re in, in which movies are losing power and internet-based work is still ascending. It was reassuring as a viewer to have this movie that feels very much like it comes from the internet. It reaffirms the capability of movies to speak to the present moment even though they’ve been displaced.

JG: In 2016, when I made Clouds Moving, the idea was the post-as-concept, like the post was an important way to think about art, and the captions and the websites things went on were important. A lot of people were doing things like this in the 2010s and it made sense because the internet was so cool. I was making these funny couches and then posting them on Craigslist as though I were giving them away. The time of day or the website where you posted meant something. These specifics enhanced the work. But as time went on, I had a sad feeling about this stuff disappearing. I have the files and the documentation, but the post goes away down to the bottom of someone’s feed. It’s there, but there’s so much else down there that it’s essentially in hell. Then I had a moment during the pandemic where I was like I need to make a big change in how I approach my career. The athletic nature of making a new piece of art every day for Instagram was not sustainable. I wanted to make things that could last a little longer.

I hear what you’re saying about film being an antiquated art form compared to what’s on the internet. And I was resisting it for a long time for that exact reason. I was like, I want to do the new things: I want to keeping making HTML stuff for silly websites, I want to keep playing around with video games. But somehow these internet art forms don’t have the emotional power. They don’t have the place in people’s lives that a book or a song or a movie has. It’s important to me to try to make someone’s favorite thing, even if it’s not everyone’s favorite thing. I think most people don’t have a favorite Vimeo-based, expressive, moody, one-minute long piece. There are examples like, This tweet changed my brain chemistry, or I think of this Instagram post every day, but I think in general we’ve left that really special era of the internet where not only could you play around, but you could get people to pay attention to it. I think you can do one or the other now. Maybe I’m just getting old.

PD: Were you a fan of traditional animation growing up?

JG: Yeah. Visually, the touchstones that have stuck with me and inspired me were the classic stop motion works like Rankin/Bass, Gumby, Frog and Toad. That stuff is a little more understated and gentle, and has a cheapness to it. Animation is certainly not something that I thought about doing with my life until I was like 23 or 24 and had already gone through a number of failed careers as a writer and as a musician. This movie is a way to get revenge and get all that stuff in front of people. I can trick people into listening to my music.

PD: I kept thinking that the film felt handmade. It’s not as though anything is made out of clay, or is even meant to be a facsimile of clay. It’s clearly made with computers, but, like in those old stop motion films you mentioned, you can feel the creator’s hands in the image. In this case, you can feel the animator’s hand moving the mouse.

JG: I had a couple animators come in and help with the character animation, but for the most part, it was me at the computer. When it’s just one person, you really can tell intuitively, no matter the medium. Common wisdom is that film, animation specifically, is a pipeline, a Henry Ford-style machine and animators are each little pieces in it, and that’s how you get the best animation. I kept thinking What if animation was like a novel? What if you just had the file that the movie was in and you could just come in and pick at it, at your leisure and not really have to worry about it. That hand that you are feeling, the hand that is moving the mouse, that is my obsession.

PD: The film has a lot of open discussions about capitalism that are very specific. You really work on these ideas in a way that I found refreshing and not reducible to righteous but glib “Blame Capitalism!”-type memes. The dignity of work and the surfeit of options for consumption are at the heart of the piece.

JG: Jack Corbett, who plays the main character is best known for his NPR Planet Money podcast and tiktoks. Talking to him, what got my brain worrying was thinking about economics as America’s religion, and the way that it’s so big and ill-defined that we can each have our own approach to it. In the film you have Jack’s character, Billy 5000, who’s very much in hustle culture in the beginning. I don’t know if you’d call him a material conditions guy or an anarchist dropout. And then you have this YouTuber he watches who’s into the mysticism of money. This combination of astrology and the stock market was common during the pandemic. Every character in the movie has a motivation based on their relationship to economics. Without spoiling the movie, Billy has to make a choice about living under capitalism. You can succeed and you can accumulate, or you can be an emotionally fulfilled person.

The big question of the movie, one that all the characters are facing, is what is your best possible outcome when there are no good options in front of you? What do you have to tell yourself to find a beautiful life within the hell of suburban Florida and the gig economy?

PD: Lastly, can you discuss the presence of clouds and eggs in your work?

JG: With clouds, I have a good answer, which is… well maybe not a good answer, but it’s something I’ve thought a lot about. I made a film called Sky Baby in 2018. It was a comic that I turned into a film that was about free association with the shapes of clouds. At one point I thought of developing a new form of horoscope, where you could do a cloud reading.

PD: I’m totally maxed out on astrology right now, but I would be very into this.

JG: Maybe I’ll pick it back up. The idea is you get a guide book or an app or something, and if you had a question you could look it up the first cloud you saw and there would be some answers. The shape would be part of it, the height, if it’s straus or cumulonimbus, or whatever, the color. It would be more like Tarot. Clouds are easy, artistically, because they’re extremely potent like that. They’re magical floating shapes in the air.

Eggs are kind of the big thing in this movie. Pivotal scenes happen at the egg restaurant. There’s the egg song. In 2022 I got two baby ducklings and started raising them. Part of their deal is that they lay eggs. So at the time I was looking at eggs a lot. They’re everything, because it’s where life starts. They feed us. In caring for these ducks I was finding a new side of myself that was not time-efficient. This side was nurturing. It took me a long time to feel like I wasn’t wasting my day being out in the yard with the ducks, sun up to sun down, just enjoying them, and taking care of them. And cleaning up after them. The eggs kind of represent something that is more ancient than money, something that actually has substance at its very definition.