MoMA’s comprehensive career retrospective of director Robert Altman continues through January 17th, featuring rarely seen early industrial films, shorts and television work as well as his feature films, the majority of which are screening on 35mm. Kathryn Reed Altman, Robert Altman’s wife of 47 years, talks with Screen Slate’s Vanessa McDonnell about his path from television to feature filmmaking, his immediate and extended filmmaking family, and his love of evenings spent with football on the television and a joint in his hand.

On Friday, December 19th at 6 PM at MoMA, Kathryn Reed Altman will be joined by co-author Giulia D’Agnolo Vallan, screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury and actor Michael Murphy for a book signing of Altman, a memoir and collection of family photographs with essays by E. L. Doctorow, Jules Feiffer, Pauline Kael, Alan Rudolph, Lily Tomlin, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and others. At 7:30, she will join Tewkesbury, Murphy, and Ronee Blakely in introducing Nashville. On Saturday, December 20th at 7:30 PM, MoMA will screen Robert Altman’s short film The Kathryn Reed Story, a film that he made for his wife on the occasion of her birthday in 1965. The film is screening with A Perfect Couple.

Vanessa McDonnell: How did you first learn about the MoMA retrospective? Do you know how and why it came about at this point in time?

Kathryn Reed Altman: Ron Magliozzi, the curator, is a huge Robert Altman fan, and this is something he’d been wanting to do for quite a while. He came to me two or three years ago to talk about it. It takes that long to get these things going, isn’t that amazing? About the same time, Ron Mann, the Canadian documentarian came to me about a film and Abrams publishing company came to me about a book. So these three projects were developing over the same time.

VM: I was able to read the book and it’s a timely and interesting companion to the retrospective.

KRA: Isn’t it terrific?

VM: There have been other Altman retrospectives, including one at the Hammer Museum earlier this year, but the series at MoMA is the most comprehensive to date. I think it’s exciting for a lot of people to see the early industrial films and television that Robert did. You can’t help but look for signs of the Altman that will emerge later.

KRA: Absolutely. Most of those were made before I knew him, so I’d never seen a lot of them. They found many of the prints at the University of Wisconsin. It’s fascinating to me that there are people who are so interested in all these many different facets of film, holding onto things that the average person wouldn’t think twice about. They build these great collections.

VM: When you first met Robert, he’d recently left Kansas City and industrial filmmaking behind. He was directing the television series Whirlybirds in Los Angeles and you were appearing on the show. There’s a charming story about the first time you met.

KRA: Here it comes…

VM: You must be tired of repeating the story! I’ll do it for you—Robert asked you, “How are your morals?” and you replied, “A little shaky, how are yours?”

KRA: I can’t imagine what I was thinking when I said that, and God knows I never dreamed what would happen.

VM: At that time, do you think he knew where he wanted to go as a filmmaker?

KRA: Yes. I’m sure he did. He didn’t walk around saying, “I want to shoot feature films,” but he was pouring himself into the creative facets of what he was doing, and it just happened to be television. Then when he did as much as he could possibly do in television, he quit and laid off for a year. He ended up with a small feature called That Cold Day in the Park, which very few people saw. This was his first film with Sandy Dennis. That led to MASH. But yes, I’m sure he did know exactly where he wanted to go.

VM: What did you think at that time about his aspirations? Did you think that he would reach the level that he did?

KRA: No, I never thought about it. We had a very lovely life. We got married in ‘59, and moved from an apartment to a modest but nice home in Mandeville Canyon in Los Angeles. We had various kids in and out—he had three and I had two—and we ended up having three more together. We had a swimming pool and he was doing television and we were having a lot of good times. I guess I thought that would be it. When he directed MASH, I thought of it as an extension of another television show. But then it changed our lives completely. We sold the house and sold the kids [laughs]. But no, really, I didn’t even realize it was happening until I looked back on it and said to myself, “God, that one film did it.” Isn’t that interesting? One film can make or break you in this business.

VM: It’s remarkable because in the years prior, he’d had major setbacks, either getting fired or quitting several projects. He’d been forbidden to shoot a particular episode of Combat! and did it anyway while the producer was out of town, and then he was removed from the feature film Countdown by Warner Bros. for using overlapping dialogue. He quit the Kraft Suspense Theater and said publicly that it was as bland as their cheese.

KRA: It was, it was blander than anything. At that point, nobody had ever heard of him. He wasn’t well known at all, or even known—he was a television director. Then he defied their rules and complained about the show’s stories and their system, that you couldn’t change a line and so forth. He gave this interview, and suddenly everyone was talking about it: “Bob Altman said that Kraft Theater plots were blander than their cheese!” A really good friend of ours sent a large case of velveeta for his birthday.

VM: I’m really curious if you’ve seen Corn’s-A-Poppin’, which Robert co-wrote with Robert Woodburn very early in his career.

KRA: I have never seen that. He used to blow that off. If it came up, he’d say, “Oh yeah, well that thing…” I’d ask him, “What was that?” He told me that he and one of his friends in Kansas City put together a spoof on Hellzapoppin’, the big broadway hit. We never had a print of it, he never did either. I mean, I don’t know where in the world MoMA got this stuff. I missed my chance to see it.

VM: I saw it and it was a big hit with the audience. The theater was quite full of people.

KRA: There were people there? Full of people?

VM: Yes! And they really enjoyed it. The film seemed to dispel all cynicism from the room. It’s silly, but feels very self aware, sarcastic even. Kyle Westphal from the Northwest Chicago Film Society was there to introduce the film. They did an amazing job of restoring the film.

KRA: I just have to see that.

VM: You should have MoMA screen it for you.

KRA: Yes, I can see it now, a private screening of Corn’s-A-Poppin’.

VM: MoMA showed a great short film with Lili St. Cyr before MASH.

KRA: She was a famous stripper, Lili St. Cyr. She had a big night club act in Hollywood and was really hot stuff. That one is a scopitone film, they were like jukeboxes with a screen, and you could pick out what you wanted to see and put a quarter in. This was the kind of thing that he did when he didn’t have a movie to work on. There’s another one he made called Girl Talk which is pretty good.

VM: People talk about Robert’s friends and frequent collaborators, the actors, producers and others, as being part of a family, and you and later your children were involved in his filmmaking. Did you feel that his professional life and his private life were intertwined?

KRA: Absolutely. Completely intertwined. I didn’t extend myself too much into his actual filmmaking, but I was always there. He shared everything. Too much, even—he couldn’t keep a secret. I was always a part of everything. I always went to dailies. He was big about having everyone gather to watch the dailies. Once it while, there would be actors who didn’t want to see themselves, but usually before the shoot was over they’d end up coming. He wanted the actors to see themselves and each other on the screen, and to get to know them on a social level, away from the cameras. We’d have drinks and food and a general festive atmosphere. I saw every foot of film shot, ever.

In those days, a lot of directors didn’t want their actors to see the dailies. They felt that it would make them self conscious about what they were doing or interfere with character development. But Bob made it enhance the process. And it was fun. Especially on location when everyone’s dead tired and they’re just going to go back to their hotel, it’s fun to come in and put your feet up and have a few drinks and start talking to each other instead. Especially when we were all traveling, like in Nashville, or Calgary or Montreal or Mississippi, it really worked well.

VM: Speaking of Nashville, your family lived in that cabin which appears in the film.

KRA: Oh God. He thought he was doing us a favor, I think, but it didn’t have air conditioning, and it was extremely rustic. But it worked, because we’d have these big barbecues every Sunday and Bob would stand behind the barbecue and cook, and actors could come over and talk to him instead of him having to go from person to person to discuss how their week went. He had that all figured out. He said, “I got this big barbecue,” and I thought, “What?” Because he wasn’t one of those guys in the backyard barbecuing.

VM: He had ulterior motives.

KRA: He sure did.

VM: Was it ever difficult for you? What is exhausting? You moved from place to place a lot.

KRA: At the beginning I really had to stop and think. Because I had all these kids. I had three kids on the first location. But I came up with a system. I had a steamer trunk for all the toys. And one for the kitchen stuff. I had it down pat, I knew how to do it. It was difficult for the kids. Not at the time, but their education was not as complete as I wish it could’ve been. We should’ve seen that it was. Somehow or other it slipped away. They would spent their summer vacations on the set, and they just stepped into various crafts. They’re all behind the camera now.

VM: It’s remarkable that Robert was able to constantly make things happen. It seems like he was always moving forward with something, and doing it the way he wanted to.

KRA: That’s right, he generated his own career. We’d go to the festivals with a film—it started with MASH where people were talking to him about MASH and he would answer quickly and then start talking right away about his next film, which was Brewster McCloud. He didn’t dwell on the film he’d just finished, that was over as far as he was concerned.

VM: And when things didn’t go as planned…

KRA: He’d find something else. First he’d sink, for about an hour. Then he’d get something figured out. I would watch it happen, I could almost see his brain working. Specifically, in the early 80s, we leased out our house because we were going to go somewhere for a film. Then the deal fell through. We were stuck in this tiny space we had in New York with two of our children and one grandchild. We couldn’t go home and we didn’t have any money. He got this idea of going to London and we found a very inexpensive place there. He worked on making connections with various people but he was very nervous. One day we took a hovercraft over to Paris for the day and then he stayed there and connected with this PR person. When he got back to London, he said, “Listen, I changed all the air tickets and we’re going to go back on the Queen Elizabeth.” I said, “What are you talking about?” He must have done some hustle and gotten some money and also made a deal for his next project. The kids loved sailing home but Bob got bored to death because he couldn’t drink and the gambling room was really small. He turned to the theater around that time. He met a playwright he really liked, Frank South. Frank wrote two one-act plays and Bob found a church over here, Saint Clemens, and put the show on, calling it 2 by South. It was filmed for PBS. That project, in turn, led to Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, and then Secret Honor, which I just saw at the retrospective in California with Phillip Baker Hall. He did such a fabulous job.

VM: That period was right after you left Los Angeles, after Popeye, when Robert talked about “breaking up” with Hollywood. Do you remember what happened with Popeye?

KRA: I don’t know what happened with Popeye—I don’t know why it got the reviews it got. Of course it has had the longest life, and it’s made a lot of money. But they just didn’t like it. I don’t know what they were expecting. The score is phenomenal, and Shelley Duvall and Robin (Williams) were perfect. The town’s characters, he got almost all of them from Big Apple Circus here, and I just thought it was terrific film. Paramount didn’t like it. Bob Evans was running it, he was coked out of his brains all the time. That’s the one thing that Bob never did. He smoked grass and drank but never until the sun went down. He tried coke one time and said, “That’s it, boy, that’s a really addictive drug.” But a lot of those executives were doing it, big time. We had a lot of weather problems and we took the film over budget. Then there was Gene Shalit’s television review.

VM: I just watched that and was laughing out loud—at him, not with him. I’d forgotten about him and his clownish routine.

KRA: Well, good. But honestly, Bob’s discouragement and his disappointment in this business never lasted long. I nicknamed him “the rubber band.” He would come right back. Of course he’d have bad moments and he’d growl and holler at a lot of people—never defenseless people, mind you—but then he’d let it go and be off into another project. It’s a wonderful trait.

VM: Speaking of nicknames, Frank Barhydt, who co-wrote Short Cuts, HealtH and several other screenplays for Robert’s films, talks about how you also called him “Kansas City Bob.”

KRA: Oh yes. So many friends started to become awed by him as he became well known. They’d say, “Oh I don’t want to call, what if he answers the phone? I don’t want to bother him.” And my line was, “He’s just Kansas City Bob.” He was a very easy, accessible, lovely, soft human being. Frank Barhydt and Bob were both from Kansas City, from that typically midwestern culture.

VM: You’ve pointed out that the two films Robert wrote from scratch are 3 Women and Images, which is so interesting in light of his overall body of work. These are both centered around women and women’s inner lives and they’re also both very poetic in style.

KRA: It’s another one of those many layers to Robert. We were broke when he wrote Images—he wrote it before MASH but it didn’t get done until after. He hated to write because he found it very lonely. So he and Bob Eggenweiler, who was a producer and part of his company and a big part of our lives, went up to Santa Barbara and rented a place right on the beach. They holed up there, just the two of them. Bob would talk and Eggenweiler would type, and then they would talk together and then Bob would talk more and Eggenweiler would type more. And they wrote the script in three days that way. And Eggenweiler would cook—that was one of his other talents. I love that film. 3 Women came to him in a dream. A strange dream. I was in the hospital at the time and he came to see me there and said, “I had this weird dream last night.” He dreamt that Matthew, our little boy who was about 7 years old, had come in from playing on the beach and gotten in bed with Bob, and that the bed was all sandy. He woke up in the night and cleaned the sand out, and then he had an idea for a film and wrote it down. This was all a dream though, he hadn’t actually written anything down. He left the hospital and drove right over to Fox to see Alan Ladd Jr., “Laddie,” who was in charge. He sold that idea to him right then and there even though there was no script yet.

VM: Robert famously put marijuana to excellent creative use. You’ve talked about how “when the sun went down he needed something to change his temperature.”

KRA: He would sit here in the living room and I would be in the kitchen or somewhere doing something. He’d be watching football and playing this solitaire game that the French-Canadian cameraman Pierre Mignot taught him—nobody else could ever figure it out—it’s a solitaire game but you play with tarot cards. He’d be here shuffling the cards and watching football, and he’d smoke a joint. That was heaven to him. I’d be upstairs listening to music and I’d say to him, “Come on, come back to life, we’ve lost you, you’ve gone wandering.” He’d say, “No no no, I’m working, I’m working, I’m getting some very good ideas.” And he probably was, who knows? I miss things like that so much. I can’t believe it’s been 8 years.

VM: Do you watch the films nowadays?

KRA: I don’t go take them off the shelf and play them. I know they’re there which is a good feeling, I’ve got a whole collection. There was another book, Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, and when that came out there were various screenings, and then there was the 40th anniversary of MASH, and now the retrospective, so I see the films on those kinds of occasions. The Long Goodbye is so wonderful, and California Split. God, every single one is just so terrific. Each one brings back memories of a whole time in my life.

VM: A lot of Robert’s films have political themes. But his vantage point often feels one step removed. There’s an anthropological bent to it, like the political process is another facet of human behavior to explore.

KRA: That’s interesting. He was definitely a very strong democrat and extremely liberal. He didn’t dwell on politics though, he didn’t get on a soapbox but he certainly had specific opinions and he would discuss them socially. They would get interjected into his films somehow or other because they were part of his nature. I would have loved to hear his take on Obama. We saw him make the keynote speech at the 2004 convention because Bob was doing Tanner on Tanner, and we were there at the convention.

VM: Where do you think Tanner ‘88 came from? The approach was radically new—it’s not quite totally fiction but definitely not documentary. It’s disorienting in a very exciting way.

KRA: It was very unusual for its time. It started a whole genre—you see The Newsroom which is on now and they’re still doing it.

VM: It’s interesting that MASH spawned the television series—which I know Robert was not at all a fan of—and then Gosford Park led writer Julian Fellowes to create Downton Abbey, and of course Tanner ’88 had so many imitators.

KRA: You’re right. I see these shows and say, “Oh God, it’s Tanner ‘88 again.” It’s realism, it’s reality. If you were in a campaign office like that, that’s exactly what would be happening. We all see it but he was transferring it to screen. He loved that project. It was a great combination of Garry Trudeau and Bob—they are so different.

VM: Michael Tolkin, who wrote The Player, has an essay in the new book.

KRA: I know they didn’t gel. I remember that Bob tried to explain to him, “Once you give this script to me, it’s mine.”

VM: From his essay, I had the sense that he gets that now, but he does talk about how it was a struggle for him at the time. One thing he says, and he’s quoting Jean Giradoux here, “Only the mediocre are always at their best.” Robert himself said that “all of the best things in my films are mistakes”. He took risks that few others have been willing to take. Do you think he gets enough credit for that?

KRA: Yes. I think that’s what his reputation is. Certainly it encompasses that. He is seen as a risk-taker, a rebel, a maverick.

VM: He was making films within the studio system, and they are so daring compared with a lot of what is being made today, independent film included.

KRA: Well the system is so geared towards commerce. Bob used to say that art and commerce just don’t gel and that the studios are making films for fourteen year old boys. He figured out a way to have major distribution with many of his films, but he was never really that connected to the studios. He’d get the money to make the picture and then he’d have to arrange the distribution. He’d fly under the radar as much as possible. He used the system to be able to make his art and to get it out there. They were breathing down his neck and there was constant conflict. There was always an enemy. There was always a heavy.

VM: Did the constant conflict get in the way?

KRA: No, never. He didn’t let it.

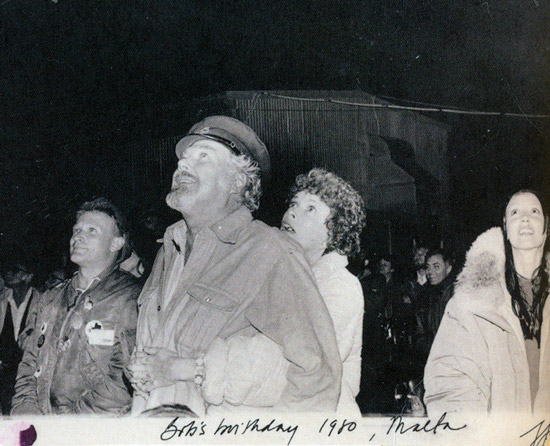

VM: What can you tell us about Robert’s short film The Kathryn Reed Story?

KRA: He made the film as a surprise for my birthday. The James Dean Story was one of the very first things Bob did with his partner George W. George and it was shortly after James Dean died. Bob was the first to pair the sound from interviews and still images together, which has now become part of all documentaries. They went back and interviewed all sorts of people in Oklahoma where James Dean came from and they had all of these great photos. They worked with Saul Bass and it was narrated by Martin Gabel who was this big shot voice-over artist on the radio and television. Bob made The Kathryn Reed Story the same way – it’s a take-off on that and very funny. He had all these good friends of ours running around behind my back and I knew all this preparation was being done but I didn’t know what the hell he was doing. I thought, “Is he going to make it like ‘This is Your Life’ and have my ex-husbands come out?” He seated me with my best friend from grammar school next to me in this empty room off of his offices, and all the people came in and there was a tripod with a screen on it and a 16mm projector and that picture. He said, “This is for your birthday.”