Yesterday, November 29, the Gaza municipality announced that the Israeli military had bombed the city’s Central Archives. In recent weeks, they have also ruined Gaza’s main library, the Rashad Al-Shawwa Theater and Cultural Center, and countless other monuments, archives, and public spaces. The IDF’s targeting of these locations continues a decades-long attempt to efface the fabric of Palestinian history. In the words of Gaza Mayor Yahya Al-Sarraj, occupation forces aim “to destroy everything beautiful, to erase Palestinian memory, and to impose a policy of obscuring the people, making Palestinian cities uninhabitable.”

An event at the Maysles Documentary Center tonight will celebrate the history of an organization whose memory the IDF has attempted to destroy. The event, co-hosted with Columbia University’s Center for Palestine Studies, will launch the English translation of Khadijeh Habashneh’s book Knights of Cinema: The Story of the Palestinian Film Unit (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023, translated by Samirah Alkassim and Nadine Fattaleh).

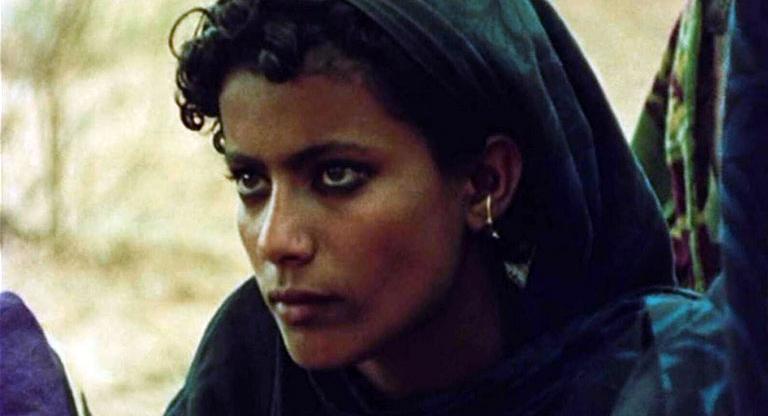

Habashneh (also known as Khadijeh Abu Ali) joined the Palestinian Film Unit (PFU) soon after it was formed in Jordan following the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, by the refugee filmmakers Mustafa Abu Ali, Sulafa Jadallah, and Hani Jawharieh. Threading personal recollections and interviews, Knights of Cinema narrates the organization’s origins as the PLO’s photography department and its members’ understanding of cinema as a means of collective, militant action. Screening films in refugee camps, PFU members encouraged viewers’ critical participation in their nation’s cultural preservation. Abu Ali’s They Do Not Exist (1974), one of many films explicitly made for international audiences, references Golda Meir’s declaration that “It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine. . . . They did not exist.”

The PLO relocated to Beirut in 1974, and Habashneh assumed leadership of the PFU’s Archive and Cinematheque, renamed the Palestinian Cinema Institute. In 1982, during the Lebanese Civil War, the Israeli military entered Beirut and looted its archives. Habashneh’s feminist documentary Women in Palestine (c. 1978) is among the films that remain lost, perhaps buried in the IDF’s own archives.

Several contemporary Palestinian filmmakers have focused on the stolen archive and the hope of its recovery. Azza El Hassan’s Kings and Extras: Digging for a Palestinian Image (2004) documents her search for missing films in Beirut; El Hassan also founded The Void Project, which gathers and restores prints from filmmakers and their families. In Off-Frame AKA Revolution Until Victory (2015), Gazan filmmaker Mohanad Yaqubi gleans PFU films from the archives of its Third Worldist networks and collaborators, highlighting the structures of global militant cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, when Palestinians collaborated with Vietnamese, Yugoslavian, Chilean, Japanese, and Yemeni filmmakers, among others.

Many PFU films survived as prints previously smuggled abroad, some only in fragments: viewers of They Do Not Exist will read at the end, “This film was rescued from a 16mm copy, where the last minute was missing.” As Kaleem Hawa writes in an essay on the PFU, “the expectation of impermanence or ruin often colors the production of Palestinian art to begin with—like a cameraperson nearing the end of their reel, Palestinian artists must work to make the most of the time they have.” Hawa locates the legacy of militant cinema in Gazans’ cell-phone videos.

Knights of Cinema: The Story of the Palestine Film Unit takes place 6:00pm tonight at Maysles Cinema, co-presented with The Center for Palestine Studies, Columbia University.