In Landscape Suicide (1987), Wisconsin's own James Benning obliquely documents the horror of two distinctly American "true crimes": Boogeyman Ed Gein's murder of Bernice Worden in Eisenhower, Wisconsin and California teenager Bernadette Protti's stabbing of classmate Kirsten Costa in 1984. Assembling police report fragments, his trademark landscape footage and longform reenactments to triangulate each story, Benning bisects the film into mirrored reports on regurgitated folklore. Both incidents and their perpetrators continue to receive the TV movie, podcast and documentary treatment, but Landscape Suicide gets closest to the metaphysical heart of the crimes, in part by wedding them to the sites and culture enclosing them.

Each half of the diptych features a long drive through their locales—a warren of suburban split levels and the desolate dairy tundra—with hellfire preachers bleating on the radio. Static shots of cloud passing over the highways and hills of Northern California or a doe tiptoeing through snow similarly establish a sense of these locales. Such "establishing shots" resemble in composition their cousins that bridge spatio-temporal gaps in mainstream narrative cinema, but here remain on screen long enough to demand their own reckoning. Minutes spent gazing upon these locales in their simultaneous splendor and banality produces a fascination not dissimilar from our appetite for grisly "true crime" yarns: how do we reconcile violent enormity with quotidian detail?

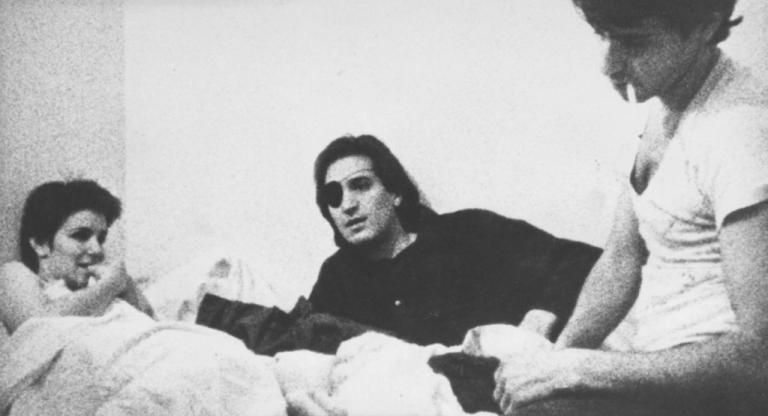

Benning's approach provides more than protracted gazing, profound as that experience is. He grants each killer a length re-enactment of an interaction with the authorities. Recorded in static medium shots, the deadpan delivery of nonactors Elion Sacker and Rhonda Bell, portraying Gein and Protti, respectively, is punctuated by blank screens that force our reflection beyond the dissipating horror of ghastly tidbits and into unsettling questions of proportion and culpability. Both deny premeditation and claim ignorance of their ultimate motivation. Benning avoids the comforting psycho- and sociological conclusions that orient true crime as a genre by compelling us to consider the crimes as scarred elements beheld at great distance. Shorn of titilating CSI photos and self-aggrandizing lawmen, fogged by Top 40 radio and advertising jingles, the crimes elude our grasp. Two more ripples in the stream.

View online here