In the decade between his Oscar nominations for prestige indies Good Will Hunting (1997) and Milk (2008), Gus Van Sant released a trilogy of low-budget arthouse films inspired by real-life, Americana-steeped tragedies. All three concern young men meandering through violent corners of the American landscape, and all three feature a lush variation on Béla Tarr’s long-take style of relentless observation, courtesy of cinematographer Harris Savides. The first, Gerry (2002), saw Matt Damon and Casey Affleck lost in the desert discussing pop culture banalities while confronting imminent death. The second, Elephant (2003), followed two school shooters and their victims as they navigate the hallways of a suburban high school. The third, Last Days (2005), records the final three days of a strung out, suicidal rockstar. To Van Sant, the trilogy represented an opportunity to pursue an alternate film grammar in which unbroken time accumulates and gradually resituates the audience in relation to the performers and the camera. Both Elephant and Last Days ask audiences to consider their relationship to public tragedies made uncomfortably vivid in their banality. Last Days, however, is often very funny.

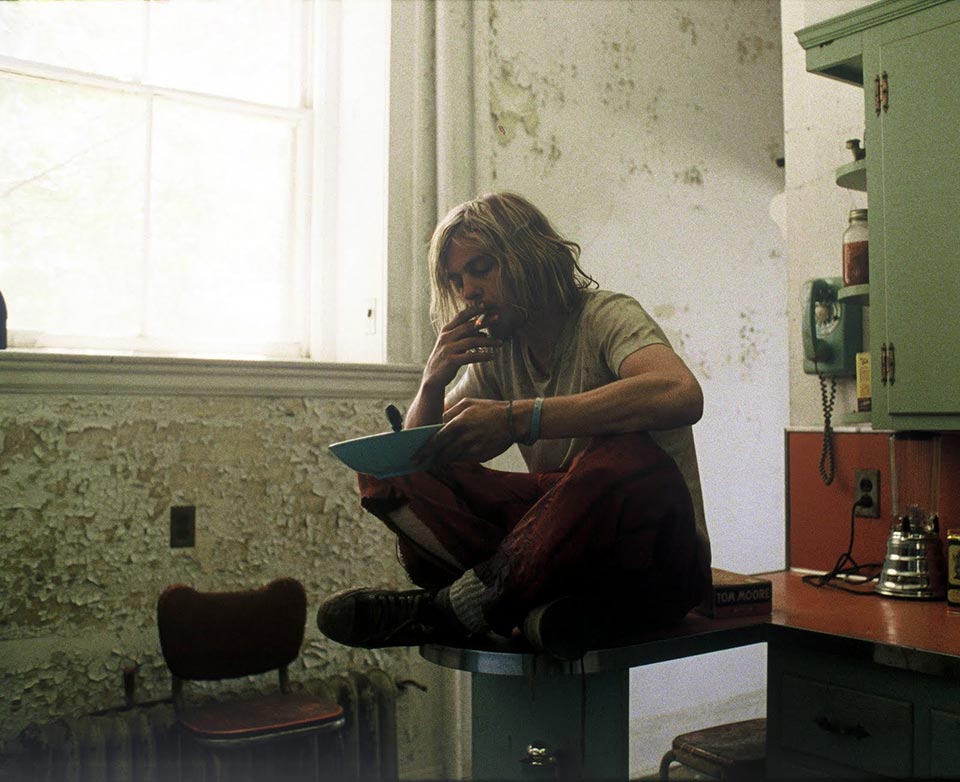

Michael Pitt plays Blake, an unwashed, mumbling musician haunting his own ridiculous mansion as scenesters, record executives and private investigators try to track him down. Van Sant lifts small details from the historical record and insists upon them for minutes at a stretch, capturing the Cobain mythology in textures and ephemera: Kraft macaroni and cheese, dingy sweaters, cross-dressing, pop contemporaries Boyz II Men, bug-eyed sunglasses, a million-dollar house with no heat, the Tom Moore cigar box. In the closing minutes, Van Sant recreates the infamous tabloid photos of detectives kneeling next to the lifeless pair of converse. Blake says maybe 50 words the entire film, but the recognition of the source is as intense as that of any mimetic biopic, without any psychologizing pablum. The film relates to Cobain as his admirers do, through conjecture and several decades’ worth of recycled images. Tellingly, Van Sant and Pitt are more interested in the dope lean than in the rituals of shooting up, the latter of which never makes it onscreen. The tension between opiates and consciousness, between the leg muscles and sedation has a balletic quality that emerges only after Van Sant’s camera refuses to look away.

Cobain’s final days have become a Clinton-era analogue to the Manson murders: everyone in Seattle was almost there, or might have seen him, or was due to meet him that very day. The film turns these near misses into a slapstick game of cat-and-mouse between the “miserable, self-destructive, death rocker” (as Cobain’s actual suicide note put it) and the various figures seeking his validation or money. As Blake flees his fortress, he walks through a lush forest on the property, unwaveringly followed by Van Sant’s camera. These are the moments where units sold and the romance of martyrdom recede behind a semi-comic portrait of man struggling to be left alone.