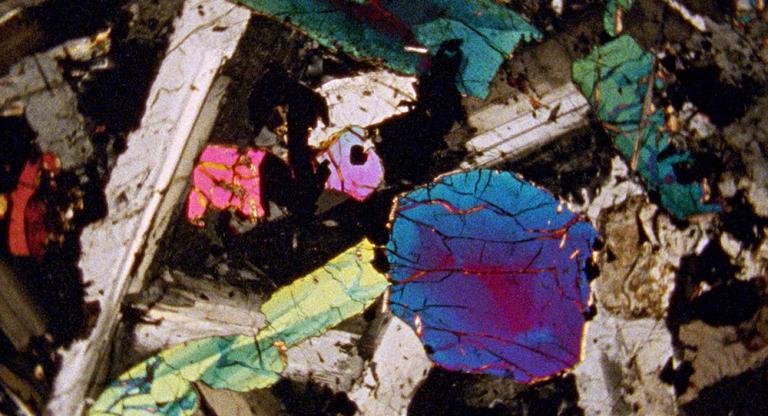

A clock designed to ring every ten thousand years chimes twice within seconds, the known universe is compressed to 35 millimeters in width, and 4.5 billion years pass by in 50 minutes. Such are the scalar operations of Deborah Stratman's Last Things (2023), a film that tells the history of the universe as inscribed on Earth’s minerals, miraculously oscillating between microscopic, luminescent views of rocks and crystals and dazzling vistas of celestial boulders.

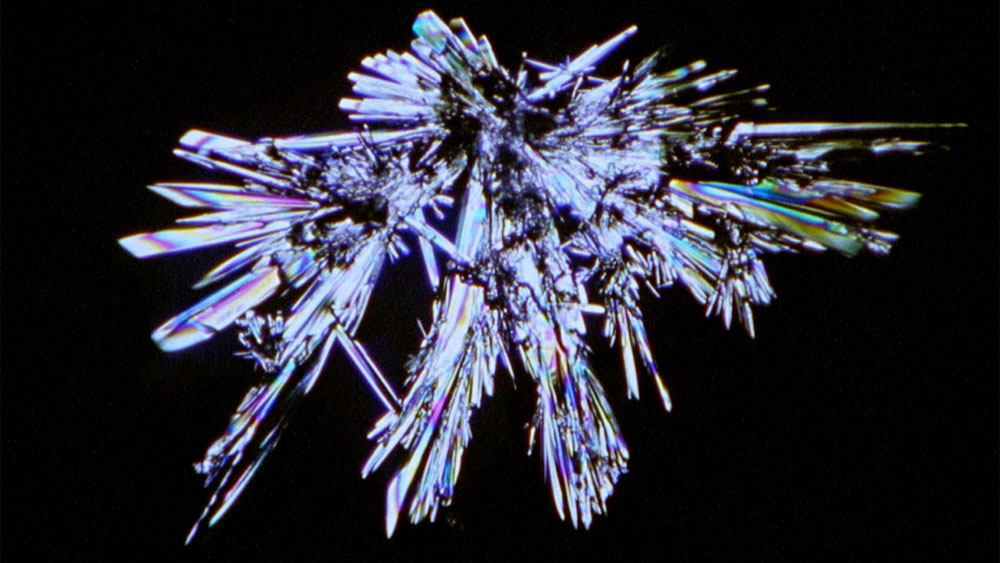

Stratman’s modus operandi consists of combining immersive sound design with things so disparate as surveillance footage, images of masculine Americana, or expansive Icelandic and Illinois landscapes, drawing unexpected connections and unearthing the systems and structures that lie underneath the surface. And Last Things is no exception. Crystalline rocks expand in slow motion; their arborescent tendrils sprout like organic lifeforms, and yet their iridescent glow evokes the uncanny impression of something contrary to life. Sonically, the film links science fiction and science fact. It opens with filmmaker Valérie Massadian reading from Clarice Lispector’s novel The Hour of the Star: “All the world began with a yes—one molecule said yes to another molecule, and life was born.” To the “yes” of Massadian’s lyrical and poetic voiceover, Last Things responds with a scientific “yes,” as the geologist Marcia Bjornerud recounts the history of chondrites, rocks, crystals, and other minerals with the enthusiasm and erudition of a devoted scholar. Stratman summons fiery passion for topics and formal techniques that would remain too icy in another director’s hands, resulting in a scientifically magic (or magically scientific) film that should appeal to lovers of nature documentaries in the style of Herzog and enthusiasts of avant-gardists like Brakhage or Frampton.

Despite its vast scope, Last Things sits squarely in our own historical moment. Implicit in its visual abstractions and temporal distortions is the absence of a human point of view, which resonates with current trends in art and academia that reject the anthro in the Anthropocene. The first half of the film approximates the non-human other through kaleidoscopic electronic music that shimmers in the background, but Stratman’s geological effort is particularly compelling because it does not pretend it can actually become other—the last thing we see in Last Things is a human dancing to analog music. The gravity of the “prehistory of prehistory” pulls, pushes, twists, deforms, and destroys linear history and narrative, but even in the vast nothingness of a pre- and post-life universe, Last Things suggests that one thing endures: beauty.

Last Things screens on 35mm this Sunday, January 28th, and next Tuesday, January 30th, at the Roxie.

Previously:

Last Things runs through January 18 at Anthology Film Archives, preceded by Cauleen Smith’s Songs for Earth and Folk (2013) and Shambhavi Kaul’s Slow Shift (2023).