The collaboration between the Palestinian writer Rami Younis and Jewish filmmaker Sarah Ema Friedland, Lyd (2024), is a science fiction documentary that depicts the once-thriving Palestinian city of Lyd, showing it in the wake of the 1948 Nakba and as it could have been had the tragic event not happened. The film features conversations with former residents of Lyd that speak poignantly of loss and absence, as well as the frustration of living under Israeli occupation. During the1948 Nakba, approximately 15, 000 Palestinians were killed and over 750, 000 were driven from their homes and villages, and had their property confiscated. “We use the story of Lyd to symbolize the story of the Nakba, the Palestinian Nakba, the demolition and expulsion of over 600 villages all across Palestine,” Rami Younis, a descendant of Nakba survivors from Lyd, said in an interview with Democracy Now. “The story of that place hasn’t been fully told, so we decided to tell it.”

Lyd cuts between cartoon-style animations of an imagined, utopic Lyd and footage of the city under occupation. The two Lyds––one free and the other occupied—present stories in counterpoint. Younis and Friedland work off this juxtaposition to make use of contrasting aesthetics, presenting a playful narrative against one that deals with devastation, and inviting the viewer to make sense of the distance between these separate histories. Throughout, a factual black-and-white text communicates the history of Lyd to avoid any confusion between the fantasy and actuality of these different representations. But it is imagination that clearly reveals itself as the filmmaker’s preoccupation, since their reliance on animation, as well as their film’s use of both glitch and dream-like aesthetics, suggests that Lyd’s ultimate power lies in its fictive dimension. Since the Palestinian perspective on Lyd has been shirked from public records, their animation puts forth a counter-record that insists on a culture and possible future denied by military occupation.

Daily interactions with the refugees of Lyd are a guiding presence in the film. They articulate the stakes of the film, call attention to human rights, and comment on the amnesiac legal structures and media coverage present in the region. The film moves quickly, between scenes of resettled Palestinians’ daily life and discussions about the Nakba. Toward the beginning of the film, we meet a Nakba survivor named Eissa Fanous. He recounts his experience being held captive as a child while looking through old images and sketches he’s kept in a folder.

“This is me, here. This is Sameer Al-Aboudi. He was with me when the Israeli army took us to Dahmash Mosque to remove the dead bodies,” he says, pointing to a small face in a black-and-white portrait of about forty boys. While the film traces the long history of war and conquest in Lyd, the history of this particular massacre during the city’s take-over in 1948, becomes its focal point. “A week or two after the massacre, they took us in the Israeli army vehicles—me, Samir Aboudi, Rasheed Fanous, Khalil Abu Judoub—no, Khalil al-Belleh—to Lyd. We weren’t captives. We were children,” Fanous continues. He is one of many interviewees in Lyd, each circulating around the events of 1948 and its afterlives.

Refugees also discuss the events of ‘48 and their survival tactics. And, the filmmakers also feature interviews with three Palmach brigade Israeli soldiers who discuss how they carried out the massacre at the mosque. The main commander insists that no women or children were killed at the mosque, but another soldier recalls how he walked away because of how many women and children populated the building before the attack; their opposing narratives reveal the truth behind the massacre.

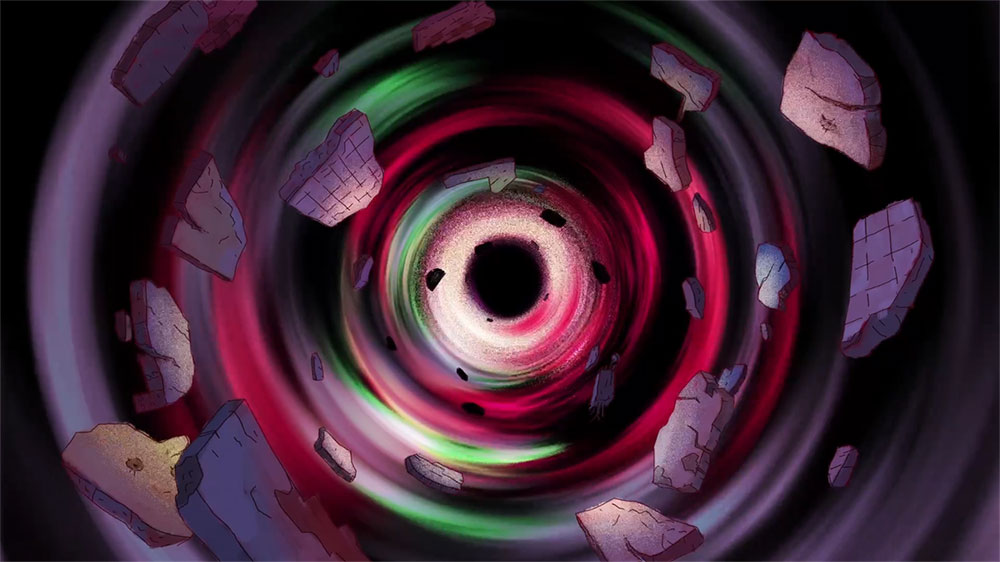

Throughout Lyd, the directors deliver long, drawn-out aerial shots of two semi-circles in the center of the city where the horrific massacre took place, as if making the center into a literal bullseye. “What happened down there was so shocking that it did not only alter reality,” the narrator says. “It also ruptured reality, opening a wound between realities.” From here, the anonymous view of the cityscape’s semi-circle evolves into a three-dimensional, green-and-pink sphere that glows on-screen, spiraling into a hurricane-like hole. In this representation, the landmark operates as an evolving piece, one animated by the possibilities of harnessing a speculative memorial and protest.

During moments like these, when the directors use their camera to take close looks at specific sites, it is as if they are showing all of history’s facts in the tiniest details from the architecture on view. “In Lyd, as opposed to Haifa, Acre or Jaffa, history was completely erased,” Orwa Switat, a city planner, says. “They used bulldozers and tractors to completely clear the historic Palestinian structures. The Israeli planning policy, from the occupation of 1948 to this day, erases historic Palestinian space and imposes their own history of this place.”

In the end, the most intimate scenes in the film are those with the descendants of Lydian refugees who interview their grandparents. In one scene, a grandmother discusses the strategies women who went into exile used to avoid robberies from Israeli soldiers. “The smartest of us buried our jewelry in secret places,” she says. When one of her relatives asks,“Where is it hidden?” She replies, “I’m not telling you!” The entire group bursts into laughter. In scenes like these, the directors suggest that depictions of Palestinians in a state of protest or joy aren’t just an element of the film’s more utopian dimension, but a crucial element of life under occupation.

Including various cinematic forms—cartoon animation, vérité interviews, archival footage, written text—Lyd resists a singular mode of recovering and discussing lost history. These formal gestures inform its narrative, which refuses to tell the story of Lyd as a smooth progression of events. Instead, these contrasting tones allow the documentary to address the contemporary expulsion Palestinians are now enduring, tracing a continuum of displacement, war, refusal, and exploitation.

Lyd screens Wednesday, August 21, and Thursday, August 22, at the Roxie.

Previously:

Lyd screens this evening, August 13, and on August 15, at DCTV Firehouse Cinema.