In 1989, the high-speed Shinkansen line from Tokyo to Yamagata City had not been built. Instead, overseas visitors to the first Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, like Kidlat Tahimik and Dušan Hanák, would have traveled the entire day through multiple legs of trains and buses into the mountains of northern Japan, through neighboring Sendai or Fukushima. Like other destination film festival cities, Yamagata’s distance from a large metropolitan center is part of its appeal—the event is even more singular because it takes place every other year. When I took the overnight bus from Tokyo Station to Yamagata City to attend the festival in October 2017, I woke up in the wee hours of the morning to see an older woman, seated across the aisle from me, intensely perusing a broadsheet schedule of the festival’s films and making her itinerary. It was my first hint that Yamagata inspired deep devotion from its audiences.

Last fall, the festival was held online due to now-familiar Covid-19 protocols, but restricted to audiences in Japan. The ten-film retrospective now streaming for free on DAFilms.com, “Made in Japan: Yamagata 1989–2021,” thus marks the first time the festival has ever presented its programing virtually to an international audience. Yamagata was the first international documentary film festival in Asia, and this program tells its history, spanning the festival’s entire existence.

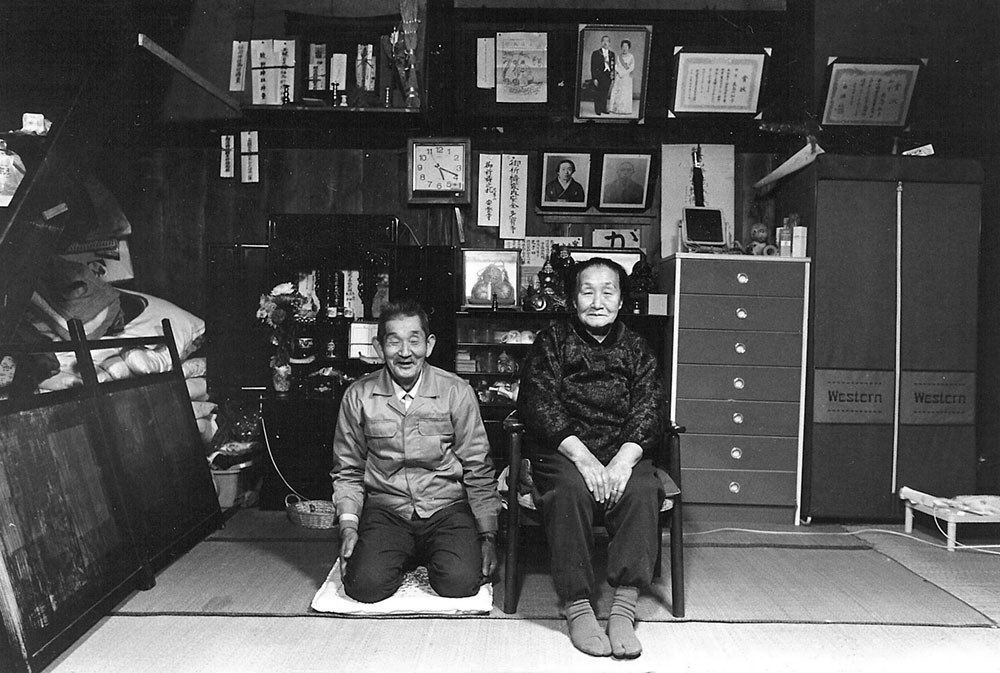

Toshio Iizuka’s A Movie Capital (1991, pictured at top) charts the organization’s early days, focusing on the filmmakers and volunteers who made the first edition possible. Other films take on social and political currents in Japan: Yutaka Tsuchiya’s The New God (1999) is a video diary provocation between a left-wing filmmaker and his subjects, the members of a right-wing punk band; Yonghi Yang takes on another maligned community, Japan’s Zainichi Korean residents, in The Cheese and the Worms (2005), a personal recording of the filmmaker’s parents. The series also represents the rise of Japan’s hottest homegrown international arthouse auteurs—Naomi Kawase’s The Weald (1997) is an episodic exploration of elders in the same Yoshino Mountains community as her debut fiction, Suzaku (also 1997)—and the present-day output of internationally-trained artistic documentarians—film.factory graduate Kaori Oda’s Cenote (2019) is a landscape film with ethnographic underpinnings, filmed across rural Mexico.

“Made in Japan” is programmed by Asako Fujioka, the festival’s longtime former director who formalized its New Asian Currents competition (an influential showcase for emerging documentary filmmakers), interpreted and translated for many international film festivals, and now serves as a Yamagata board member. Under her charge, this competition maintained an expansive definition of Asian documentary practice, platforming a wide range of films from the Asian Pacific Rim; South, Southeast, and Central Asia; and the wide Asian diaspora in the Americas, Australia, and elsewhere. Bontoc Eulogy (1995), a.k.a. Don Bonus (1995), and early videos from Gina Kim and Ho Tam were all selected for New Asian Currents during Fujioka’s tenure. This deliberately radical view, expansive sidebar programs spotlighting specific documentary traditions and schools, and the festival’s extensive online archives make Yamagata an invaluable resource for cinephiles, film scholars, and curators to delve into the filmic output of an entire continent and its diasporas. Though “Made in Japan,” which was commissioned by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, comprises only Japanese films from Yamagata’s competition history, a pluralist outlook is powerfully reflected in its assertion of who and what constitute Japan and Japanese documentary films.

One of the biggest draws to the series is Ryusuke Hamaguchi and Ko Sakai’s Storytellers (2013), made in the aftermath of the 311 Fukushima nuclear disaster, the last film in their Tohoku trilogy and the only one that the filmmakers have deemed appropriate to screen virtually. Hamaguchi and Sakai enlisted folklorist Kazuko Ono to guide elderly survivors of 311 into telling stories from their childhood. The scenes are knowingly framed by large windows that look onto lush greenery on the side of a volcano—the fertile aftermath of destructive forces. The folk stories are fantastical, and often quite dark, tales of animals and the vagaries of the natural world; a particularly vivid story involves a greedy Shinto priest who faces a moral quandary as a result of his spatula-slapping obsession. Ono gently nudges all three storytellers into revealing their childhood memories and family histories, audibly tracing the knowledge-production and community-building capabilities of folklore (and, by extension, community-based documentary production). The ending self-reflexively reveals a communal construct that calls to mind Hamaguchi’s improvisational acting workshops—which resulted in Intimacies (2013) and Happy Hour (2015)—delving into both the documentarians’ collecting impulse and the storytellers’ motivations for participating. “I wanted to find some kind of roots in my beliefs, and I wanted to find it away from the cities, in the countryside,” Ono observes.

Tatsuya Mori’s A2 (2001) could be read as an attempt to rehabilitate the reputation of one of Japan’s most notorious doomsday cults, Aum Shinrikyo. Mori started filming this sequel to his own A (1997) following notable events in the lives of cult members in the years after its leaders were found guilty of a lethal sarin nerve gas attack on a subway station in Tokyo, which killed fourteen people and affected thousands more. Shooting from the hip, shoulder, and knee, Mori continues his probe into the effects of media sensationalism by watching individual Aum members as they practice their leader’s health teachings and are hounded by vigilante neighborhood groups. He looks on as senior leaders apologize for prior wrongs and denounce former incendiary teachings, re-establishing the cult under a new name and leadership. In Mori’s view, independent documentary films and mainstream media both lie, portraying events with a biased point of view. In this film, the neighborhood watches and city council meetings seem composed of fanatics, the police are suspicious of Mori’s camera whereas the cult leaders welcome it, and fist-pumping regular citizens are as synchronized as a Riefenstahlian rally. This uncomfortable project presages Mori’s Fake (2016), an infuriating and fascinating documentary about a musical charlatan, a work as self-implicating as any more famous provocateur’s on the international film festival circuit.

Makoto Sato’s Living on the River Agano (1992) is gorgeously presented in a newly digitized and English-subtitled form. It fits squarely within contemporaneous documentary film trends, a series of portraits of different residents along the titular river, with scenes of agriculture marking the passing of the seasons. Intertitles reveal the sociopolitical significance of the setting, as the Agano is the waterway where a chemical factory dumped mercury in the 1960s, causing thousands of the people who lived and worked on its shores to suffer from a second outbreak of Minamata disease. The government denial of the original Minamata disease, and limited support for its victims, is the subject of landmark works from two other Japanese filmmakers—Noriaki Tsuchimoto, and, more recently, Kazuo Hara. Here, the confluence of work, illness, disability, the end of life, and the physicality of villagers’ bodies as they pursue highly skilled work stewarding their own lands floats in 16mm above the miasma of self-righteousness that afflicts most social-issue documentaries. Sato’s film group employed a style of working most associated with Shinsuke Ogawa, a filmmaker who was also instrumental in the success of the film festival in his adopted home of Yamagata City; the crew lived and worked together constantly over the the three years of filming, sometimes putting down their cameras and mics to help with the harvest or other tasks.

River Agano’s editorial process, the impact of a work-in-progress screening at Yamagata, and Sato’s tragic end are all addressed in detail in the most recent film in “Made in Japan,” Koichi Sato’s Pickles and Komian Club (2021). One of the most conventional films in the bunch, it was made in response to the announced closing and demolition of the pickles shop and attached restaurant, an integral hub of the film festival’s social scene. While the first half of the film incorporates process shots of its pickle factory packaging and interviews with the owner about the relentless effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the second half focuses entirely on the restaurant’s relationship with Yamagata City’s pride and joy: the film festival. The film is thus a part of the festival’s relentless self-documentation, with its portents of closures, gentrification, and difficult institutional changes. For more context, back issues of DocBox, Yamagata’s irregularly published film journal, which lasted from 1992 to 2007, are archived on the festival’s website. Pickles and Komian Club’s inclusion in a defining retrospective suggests the importance of knowing one’s history in order to know where one is headed.

“Made in Japan: Yamagata 1989–2021” streams for free January 17–24.