Metallimania (Marc Paschke, 1997) (YouTube)

Metallica Through the Never (Nimród Antal, 2013) (Digital rental/purchase)

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster (Joe Berlinger & Bruce Sinofsky, 2004) (Netflix)

Hit the Lights: The Making of Metallica Through the Never” (Adam Dubin, 2014) (YouTube)

Metallica - The Making Of Hardwired...To Self-Destruct (2016) (YouTube)

The most serious challenge of a music documentary is overcoming an audience’s indifference or antipathy to its soundtrack. There is no sense in watching The Last Waltz if you don’t enjoy its roster of blow-and-sunshine classic rock. Similarly, why should nonfans sit through Shut Up and Play the Hits? But Dig! And The Devil and Daniel Johnston, to name two, require little affection for their subjects’ body of work. The best of the genre minimize fan-service and hagiography to create a portrait rich in wider context. All three of Penelope Spheeris’ Decline of Western Civilization films attempt to chart demimondes previously labeled “Here Be Grime” on the broader cultural radar. One might despise LA hardcore or hair metal or crustpunk, but the trilogy offers an immersion in the folkways of a subculture as vivid as Martin Scorsese’s mobsters or Rob Zombie’s rednecks. Subcultural minutiae might be the antidote for those seeking shelter from news of unraveling macrosystems.

As the subject/progenitor of more films than just about any other musical concern, Metallica has dallied in both tendencies of the rock doc. In addition to countless concert films dating back to 1987’s Cliff ‘Em All VHS tape, every album since 1991 has spawned a contemporaneous feature-length making-of documentary. The latter artifacts double as promotional material and peek behind the curtain for rabid fans. Occasionally the efforts are conjoined, as with the 3D concert film Metallica Through the Never and Hit the Lights: The Making of Metallica Through the Never” , a 12-part documentary pat on the back for the band and its support staff, who beat back tremendous odds to spend $30 million of their own money on an astonishingly empty vanity project.

The most respectable entry in this massive filmography is Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, a treasure trove of slammed doors and boy feelings in which the band work with a skeezy corporate therapist to solve decades’ worth of resentments in order to finish their St. Anger album. The project began as a making-of infomercial assigned to the Paradise Lost duo of Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, but grew more legitimate as the filmmakers captured the rock titans arguing about their emotional needs while wearing flip flops and cold sores. In the film’s most sublime moment, Hetfield ponders the term “lifestyle,” the fruit of which became the chorus of the album’s first track: My lifestyle determines my deathstyle. Later, the therapist starts contributing to the band’s lyrics. Only This Is Spinal Tap tops Some Kind of Monster in its recasting of arena rock gods as vapid clowns.

The Metallica machine has kept churning since, with the aforementioned Through the Never and two more fly-on-the-wall films documenting the making of their most recent albums, Death Magnetic and Hardwired… to Self-Destruct (2016). The Hardwired doc prominently features Hetfield wearing a “Got Riff?” t-shirt, a Gen-X reference best-loved by Boomers. At this point, the band shares more in common with Star Wars than with any rock band. Both institutions dragged a derided subculture into the mainstream, transforming context-stripped childhood obsessions with war into cradle-to-grave merchandising ecosystems. And much like Star Wars, the band’s endless self-mythologizing is repackaged again and again along a conveyor of promo films, cable-TV tributes and yes, behind-the-scenes documentaries. It would surprise very few if Disney purchased Metallica for a billion dollars in order to trot out holograms for a rockin’ theme park ride.

But, as the infomercial rube cries, there’s got to be a better way! And there is. The most intriguing portrait of Metallica, the one that preserves some of the band’s appeal without glossing over the buffoonery at the heart of the operation is the semi-official documentary Metallimania (1997). It’s the film for anyone who ever felt cheated by Heavy Metal Parking Lot’s 17-minute runtime.

In defiance of the band’s “quite Hitleresque” management company (Q Prime, the braintrust that dreamed up and sold the band on Through the Never), provocateur Eric “EB” Braverman teamed up with fellow friend-of-the-band director Mark Paschke to follow “the sights, the sounds and the smells of the average Metallica fan” from 1994 to 1996. They intended to cobble together an inside joke tape to be passed around by the band and crew, but eventually the beast escaped its cage. Behind mutton chops that fall to his chest, Braverman obnoxiously thrusts a microphone into the faces of a largely white, male, working class fandom as they congregate outside arenas to drink beer and bump chests. Unworried by promotional concerns, Braverman and Paschke are free to mock the band’s avarice and lure the more lunkheaded fans into spewing drunken gems of Metallilove. Someday Metallimania will become a key text in whiteness studies curricula.

In the early going, a teenager, removed from the crowded entrance line by only a few feet, rips so hard on his air guitar that he throws himself backward into a bush. Undeterred, he climbs out to continue thrashing. This is the band’s fandom at its devotional best, a goofy abandon in which anger transmutes to cathartic groove. The fandom’s nadir can probably be inferred from the identification of the stereotypical fan as a white, blue collar man. One such subject announces his displeasure that his middle name, Emmit, deprives him of the initials KKK. He hates “communist conservatives” who want to take away his newly purchased Tec-9. Other interviewees include a methed out teenager who hasn’t slept in five days, a crewmember terrified of missing Lars Ulrich’s lighting cues, and a man straight out of the pit nursing a head wound. As Braverman puts it: “Metallica fans: in a drunken rage today, senatorial hopefuls tomorrow.”

Nearly everyone agrees on one thing: the new shit isn’t as good as the old. When the band traded the genre-defining trash of their first four records for the Heavy Rock of 1991’s self-titled “Black” album, the tailgate consensus held that the band sold out their fans and their legacy. But as with the malcontents decrying the infidelity of Disney’s Star Wars films who are nevertheless unable to abstain from each new release, these fans can’t quit Metallica.

In a repeated bit that gains unintended profundity, Braverman asks for fans to speculate on the band’s “philosophy.” It’s a gag, of course, meant to befuddle the drunks, but that doesn’t mean it’s an unproductive line of thought. Without putting too fine a point on it, the question ultimately translates to “what are we all doing here, preparing to sweat and convulse to punishingly loud noise?” Most answers are inarticulate, variations on a theme offered up by the wasted young man who claims Metallica “says everything I feel” before putting a cigarette out on his tongue. It would take an anthropologist to say for sure, but it seems pretty clear that what they’re all doing there is physically coalescing as a class in a way that feels unthreatening. It’s apparent in the mating/war dance the band itself does on stage, alternately thrusting their crotches and heads at one another during particularly juicy noodling. Like sports, metal culture offers millions of young men an arena to enjoy each other’s bodies without shame. They weave their arms around shoulders, forming a chain of shirtless dude bod. It’s a big tent of white disaffection that includes those without the emotional vocabulary or political awareness to question their station as well as the white supremacists disgusted that Showtime at the Apollo features too many black people. Some diversity rears its head as a man in a wheelchair proudly shows off a stomach tattoo reading “Crippled Supremacy.”

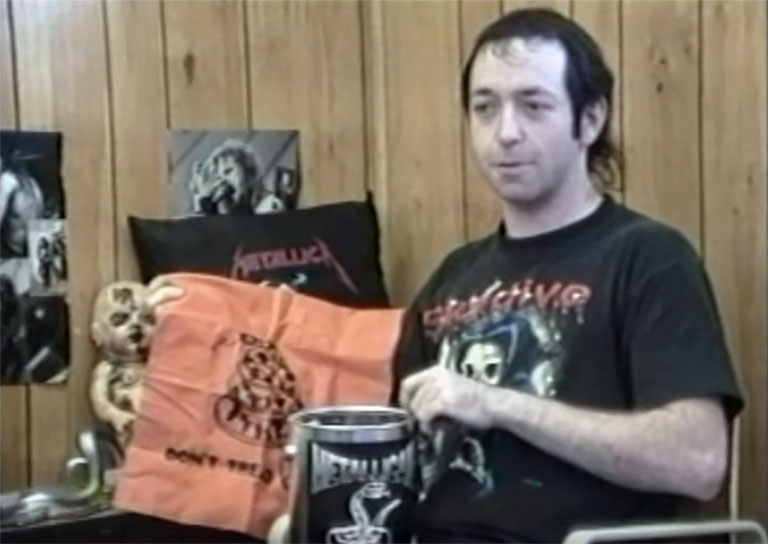

Several interviewees get closer to the mark when they sum up the band’s philosophy in one word: “money.” The band’s burgeoning gifts for merchandising are a sticking point for many interviewees, as it is for the filmmakers, who had been friendly with the group since the earlier, hungrier days. (Such is their bonhomie that Braverman can get away with mocking Hetfield’s mullet to his face.) The plethora of Metallica tchotchkes coincided with the softening of their sound. Braverman interrogates one collector kind enough to share his memorabilia with the camera by demanding to know whether a Metallica-branded pillow’s softness betrays the “idea of the band.” (Twenty years later, pillows have become some of the milder merchandising betrayals, which also include see-through backpacks, jigsaw puzzles, passport covers, infant socks, and of course, Funko Pops.) In his disgust, Braverman stumbles on another interesting question when he asks what the collector plans to do with his treasures, which he would never sell. “Probably be buried with them,” he says. “Unless I have some cool kids or something who deserve it.” As if to twist the knife, Madonna shows up in the last ten minutes to coax the band to a party at her house. Braverman asks her to name a Metallica song, with predictable results.

Metallica long ago reached the rare air of popular culture in which navel-gazing becomes the only path to authenticity. After decades of playing to tens of thousands nightly and collecting Basquiats, each of their projects has become a testament to its own making. Like a producer wanting every dollar onscreen, they don’t like to spend a dime without mentioning it in an interview or documenting the expense on tape. Called upon to describe any endeavor, the band and crew rely on variations of More/Most/Biggest/Ever/History. Like a Disney film, each effort is a hub with a hundred spokes of merchandising radiating outward. Metallimania, which no one outside of the band’s circle of roadies and assistants was ever meant to see, enlists fans to wrestle with ambivalent feelings directed toward their idols. They’ve unveiled many lackluster albums and videos and toys since then that the 90s notion of “selling out” doesn’t compute anymore. It goes without saying that now every star must become a fount of merch and multi-tiered experiences. But Metallimania escaped the machine twenty years ago, and now serves as a reminder that such things used to seem worth our anger.