This year marks the one hundredth birthday of the Stanford Theatre; this week marks the comedown of a second Trump presidential inauguration. In its wake, the Stanford presents a month-long Frank Capra festival, dedicated to the original Italian-American film auteur and brain behind evergreen favorites like It’s A Wonderful Life (1946). Indeed, Capra’s biography reads like an anecdote from a presidential campaign. Born in Italy at the tail-end of the 19th century, the youngest of seven, young Capra and his family made the journey from the Old World to the United States by boat in 1903. After a stint in the army and years of long, grueling work, Capra finally found success in 1934 with It Happened One Night. Suffice it to say that if an American Dream ever existed, Capra wholly embodied it, and he never failed to make this evident in his subsequent films, not least Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

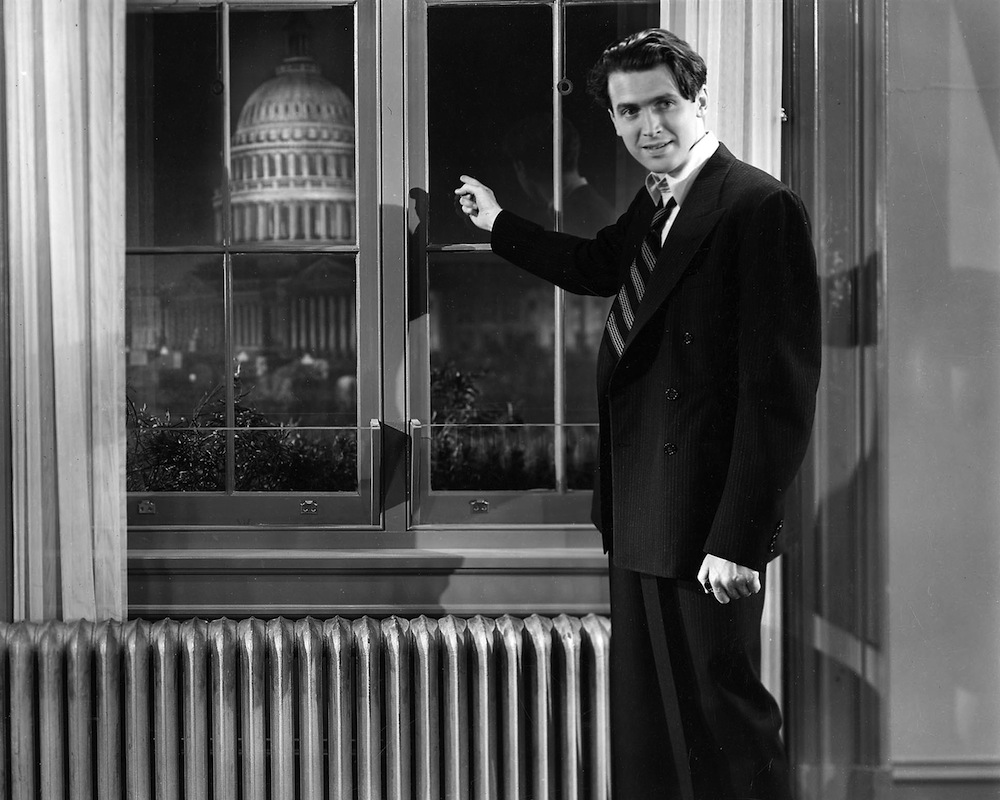

Mr. Smith functions as a political screwball; Jefferson Smith (Jimmy Stewart) is plucked from his position as the Supreme Leader of the Boy Scouts somewhere way out West and appointed/voluntold by the governor to fill the seat of a recently deceased senator. This appointment is purely, ahem, political: all of the pols are really controlled by evil industry magnate Jim Taylor (Edward Arnold), who selects Jeff based on his presumed naïveté and general fecklessness. But this all goes wrong when Mr. Taylor messes with Mr. Smith’s beloved boys, trying to skirt a dam-building scam through the Senate over Jeff’s proposal to build a national boy’s camp on that very same land. Mr. Smith, a blue-blooded patriot emboldened by a long visit with the Lincoln Memorial, throws all his efforts at exposing this corrupt political machine for what it is. Stars and stripes twinkle in Jimmy Stewart’s eyes (who would, of course, serve as one of the first movie stars to join the Armed Forces when the United States joined World War II a mere two years later.) Long speeches of justice and freedom are made, eyes turned heavenward. The Constitution is read (off-screen) in full.

Can a film program have political commitments? Can a bucket of popcorn channel ideology? The Stanford Theatre was purchased and restored to its full movie palace splendor by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation in 1987. This name might ring a bell if you are familiar with the multinational tech giant HP, founded in part by David Packard in 1939, a month after Mr. Smith Goes to Washington had its wide-release opening; later, Packard served as the deputy Secretary of Defense in the Nixon administration, four years into the US’s deployment of combat troops in Vietnam. To its credit, we can thank the Foundation for the always-cheap tickets ($3.50 per movie in 2025 seems symbolic at most, a gesture aligned with Freud’s philosophy that patients ought to always pay for therapy), the celluloid fetish, and the mighty Wurlitzer organ that floats up from the historically accurate orchestra pit as the curtains close to play “Cheek to Cheek.” For another thing, the Foundation is operated and maintained by David Woodley Packard (the junior Packard), whose only sin is inheriting the wealth made on the misfortunes of others. But one also has to wonder about the ideological investments of a theatre frozen in the Golden Age of Hollywood. To be sure, devoting millions (of which you had no fault in inheriting) to the upkeep of a pure passion project is far from sinful, and viewers ought not to feel guilty about participating. But—one might find themselves wondering.

I have seen truly radical early cinema at the Stanford. I’m not convinced that Mr. Smith, or the Capra festival on the whole, is working on that level at this moment. There are many reasons why a theater might select to showcase a particular director at a particular time, and I do not pretend to know what happens behind the doors of the programmer’s offices. Still, why Capra now given the extensive print collection that the Stanford can access? It’s possible that Capra’s America has always been a tragic one—a political fantasy more than an expression of a realized attitude. But does watching Mr. Smith on the heels of the Trump inauguration breed a courageous, steely optimism: daring to believe in a system you know to be false? Or does the D.C. tour montage, or the dramatic apex of the filibuster, read as desperately saccharine in 2025? Frank Capra loved America, and Mr. Smith is, if nothing else, a winding testament to that fact. But, to rehearse John Cassavetes: maybe there never really was an America. Maybe it was only Frank Capra. For better or for worse. I’ll see you at the theater.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington screens on 35mm this Saturday and Sunday, February 1 and 2, at the Stanford Theatre in a double feature with Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, as part of “The Films of Frank Capra.”