Not enough is written in English about the Argentine experimental filmmaker Narcisa Hirsch, who departed this plane last May at the age of 96. The filmmaker Lynne Sachs conducted an invaluable Mini DV interview with Hirsch in August 2008—an almost unbroken hour-plus document of the artist (then 80 years old) detailing the genesis of her filmmaking. She took to experimental cinema in her forties, already a bourgeois mother of three, who agreed with the massively influential Argentine art critic Jorge Ramiro Brest that “art, as we knew it, had died… Painting on an easel had died.” Hirsch says she was in an “uneasy marriage” with painting and that “movement meant a lot to me. I suddenly felt I could paint with film.” Hirsch joined her husband on business trips to New York, which is where she saw films like Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) and caught wind of interactive Happenings organized by groups like Fluxus. Soon, Hirsch was involved in experiments that were both indebted to and conceived as a response to this New American avant-garde in Buenos Aires. Especially given this lineage of ideas, it’s insane—shameful, really—that Microscope Gallery’s superb “On the Barricades” is the artist’s first solo exhibition ever in New York City. News in late 2023 of Hirsch’s films being restored in collaboration between the University of Southern California and the Filmoteca Narcisa Hirsch could not have come at a more opportune time.

The Microscope show spans just under two decades of her work, beginning with films Hirsch described to Sachs as “typical of the Sixties,” sometimes conceived as little more than excuses to gather friends and fellow artists for screenings. In her “group,” she identifies the artist Marie Louise Alemann, the poet of Super 8 Claudio Caldini, the late Uruguayan filmmaker Juan José Mugni, and filmmakers Juan Villola and Horacio Vallereggio. These names represent some of the major talents of South American experimental cinema in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, all of them overdue for more exhibitions and screenings. I should mention that last year’s Neville d’Almeida and Hélio Oiticica exhibition Cosmic Shelter, at Hunter College’s Leubsdorf Gallery, as well as the “ISM, ISM, ISM” series organized by Pacific Standard Time in 2018 counter this lack of attention toward Latin American experimental filmmakers. Caldini’s works have also been made available on gorgeous blu-rays thanks to the Antennae Collection and the Argentine filmmaker, curator, and writer Leandro Villaro. Nevertheless, opportunities to see these films are frustratingly scant both in New York City and elsewhere.

What’s interesting is that Hirsch describes this era of avant-garde art to Sachs as radical precisely because the works didn’t carry explicit political messages; rather than societal satires, polemics, diatribes, or jeremiads against American influence in Latin America, they represent structural play and personal disclosure. The earliest work on display is Marabunta, a straightforward document of a happening that took place in 1967, after the Argentine premiere of Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) in Buenos Aires, where attendees were invited to help themselves to a spread of fruit within a giant plaster skeleton fabricated by Hirsch and her compatriot Alemann. A fascinating and tragic timestamp, Marabunta was shot on a 16mm Bolex by Hirsch’s collaborator, Raymundo Gleyzer, another middle-class Argentine filmmaker of Jewish European extraction, but one whose filmmaking became direct action in the run-up to the Dirty War that began in 1976. Gleyzer was among the estimated 30,000 desaparecidos murdered by the dictatorship, which makes Marabunta a snapshot of a more merciful, open-minded time in Argentina’s history. His masterpiece, The Traitors (1973), is as clear in its blistering indictment of the junta evenly backed by the CIA, the Catholic Church, and the AFL-CIO, as Hirsch’s films are fragmented, abstract, and haunting.

As “On the Barricades” progresses, however, Hirsch’s political ideas come into sharper focus. Come Out (1974) is a visual accompaniment to the 10-minute audio piece by Steve Reich of the same name. While Reich loops, expands, elongates, multiplies, and collapses an original piece of audio—a recording of the 18-year-old Harlemite Daniel Hamm testifying, about his multiple days of being beaten by New York City police officers, that he “had to, like, open the bruise up, and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them”—Hirsch’s 16mm visuals are methodically paced, amounting to a very slow rack focus on the stylus of a turntable, playing an EP of Come Out. In Taller (Workshop), also from 1974, Hirsch suspends the camera on a shot of a wall in her home and describes the contents of the frame; eventually, her narration expands beyond the image on-screen in another hat-tip to Snow. Shot on Super-8mm, Hirsch’s impressionistic 23-minute odyssey Mujeres (1979) depicts different women in a variety of landscapes—domestic, natural, photogenic, obscure—while handwritten words are shorn of context and men appear as imposing phantoms. It’s like a retelling of Adam and Eve from a woman’s perspective, where the loss of innocence is a continuous negotiation (if not a freefall.)

Shot between 1980 and 1983, the photo series Untitled (La vida es lo que nos pasa...) exposes the emptied-out streets of Buenos Aires during the dictatorship, as the filmmaker turns her camera on her own graffiti which, like the aforementioned films, defies sloganeering and easy interpretation. Watching Hirsch work in 2024, it’s impossible not to think we are about to pass through another tunnel of history in which every last critique and observation will be threaded back to the problem of living under corrupt demagogues such as Trump, Netanyahu, Putin, Orban, Meloni, and Argentina’s own Javier Millei. Broadly speaking, this tendency is fine—what’s the use of criticism if not to decipher the insane gibberish of the present?—but artworks like these speak to a different rebellion against a different conservatism, the one which discourages people from organizing and performing, from sticking their necks out, from creating spectacles and risking making fools of themselves. This fear of leaping into the dark is just as symptomatic of the collapse of society as are the twin hegemonies of fascism and capitalism. Featuring work in equally intimate, lyrical, political, and structural registers, “On the Barricades” testifies to Hirsch’s fearlessness.

Narcisa Hirsch: On the Barricades is on view through November 30 at Microscope Gallery.

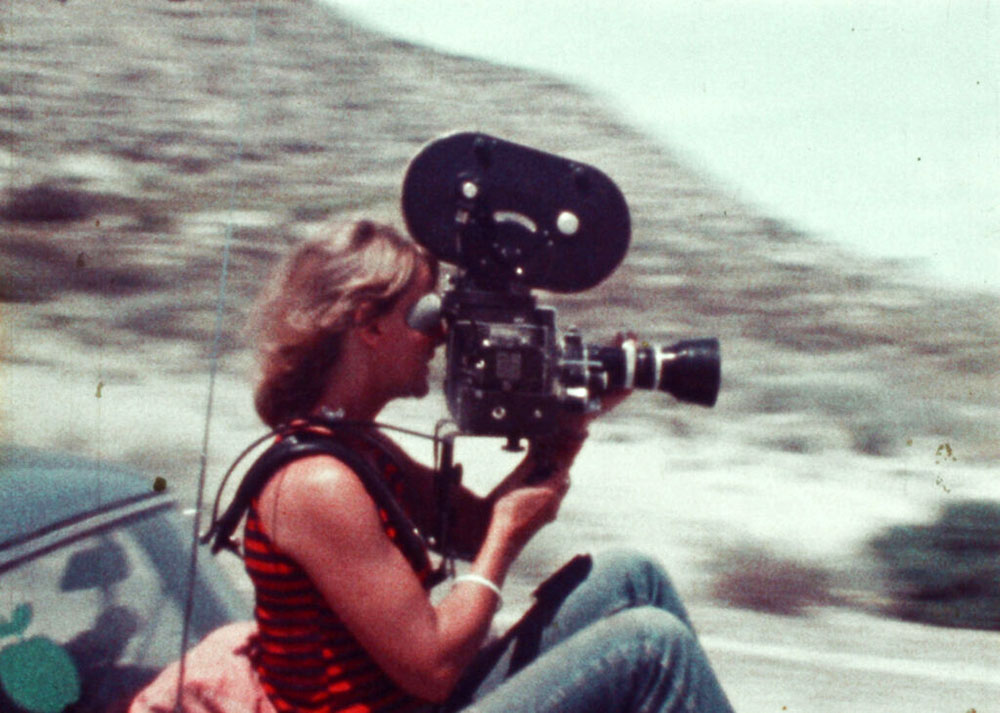

Image: Still from “Diarios Patagonicos 2” (1972) — Courtesy of the Estate of Narcisa Hirsch & Microscope Gallery