Ricky D’Ambrose’s films are distinguished by his attention to detail: Bressonian close-ups of hands, ornately crafted replicas of newspaper clippings, careful editing rhythms that suggest the edges of a scene. This minimalism often suits his subject matter. His debut feature Notes on an Appearance (2018) centers on research for a biography of a political theorist, but the book’s editor seems determined to suppress a controversial, violent past. As a young writer uncovers this history, he suddenly vanishes. It would be startling if it weren’t so obliquely conveyed. Several of D’Ambrose’s shorts, particularly Spiral Jetty (2017) and Object Lessons, or: What Happened Whitsunday (2019), also explore political obfuscation in art and academia, a theme embedded in the films’ tightly framed compositions, defined as much by what they omit as by what they include.

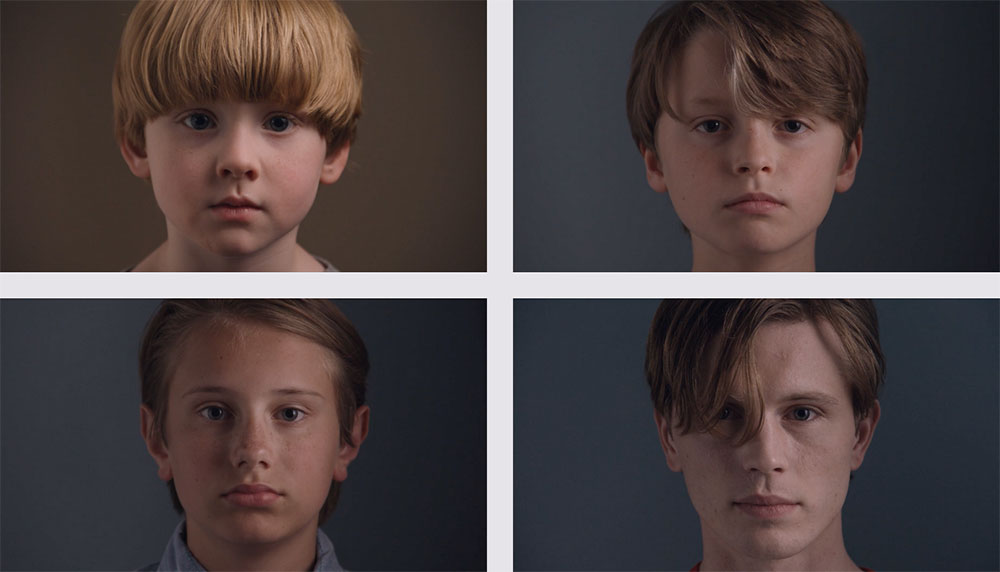

D’Ambrose’s second feature, The Cathedral (2021), takes this tone in a different direction. Spanning the late ’80s to the mid-aughts, the film charts the dissolution of an American family, the Damrosches, which was inspired by D’Ambrose’s own. It’s not a grand, Shakespearean rise and fall; instead, their fracture plays out amid the subdued rhythms of ordinary life. The Cathedral doesn’t psychologize the family, although the closest character it has to a protagonist, Jesse, would seem to be D’Ambrose’s proxy. Instead, the film observes the family in fragments, filtered through Jesse’s visceral memories of his youth: a classmate’s sudden nosebleed, the shards of a drinking glass on the ground at a funeral, and beams of light on the floorboards of a childhood home—a shot that nods more to Terence Davies than Boyhood (2014).

In anticipation of The Cathedral’s screenings at New Directors/New Films, I spoke to D’Ambrose about sense-memory, TV news, and the challenges of filmmaking in the American suburbs.

Chloe Lizotte: I'll start with my most non-sequitur question—in a way, this is literally the beginning. You’ve said that The Shining [1980] was an important early influence for you, to the point that you made a shot-for-shot remake as a kid. What drew you to that film?

Ricky D’Ambrose: When I was about nine or ten, my father used to get batches of studio releases through a mail-order VHS catalog, one of which was a natural disaster movie with Helen Hunt called Twister [1996]. I was sitting with him while he watched it. There’s a scene that takes place at a drive-in movie, which is introduced by a close-up of the screen, and what you're seeing on the screen is a shot from Kubrick’s The Shining: the boy on the tricycle in the hallway, the twin girls in blue dresses. That image was formative. It was probably the only thing in Twister that got me very excited about anything. This very symmetrical, brightly lit image, paired with menacing orchestral music by [Krzysztof] Penderecki. It seemed so colorful and clearly delineated, with such deep space and this floral wallpaper.

As a kid, it was very unusual to experience something so visually interesting and strong. I don’t think I was attracted to it because it was a horror movie; it was because of how clearly articulated things are. I remember figuring out what The Shining was, as one did, and then I rented it and learned who Stanley Kubrick was. Through Kubrick, I developed an interest in filmmaking. It was a time when I discovered that filmmaking is a result of artistic choices, like how to light space and how to use music. Every time The Shining plays in New York, I go see it—there is a precision to it that I continue to try to learn from.

CL: The Cathedral is inspired by your family, but it’s not a memoir narrated by a stand-in character—it’s more observational and nuanced. How did you want to approach the autobiographical elements of the film?

RD: I had the idea for this when I was nineteen or twenty. My relationship with my family is very loving, but it's also—if this isn't evident in the film—let's just say, complicated. As I got older, my relationship with their conflicts changed, and that distance became an important component of the film. It never escaped me that Lydia and Richard Damrosch are based on my parents, Richard and Linda D’Ambrose, and that these actors were dressed as my parents were in 1990. I was shooting this in the home I grew up in, my father's apartment, where he still lives. And these are events that happened, whether I have firsthand memories of them or they were archived on a home movie from 1988. There is an unsettling, ghostly confrontation with the fact that most of this is based on people who are still alive.

What I didn't want to make was a coming-of-age story about some boy in the suburbs who has a Road to Damascus moment, where he's the locus of emotional investment. But my politics started to form [at that age], and my awareness of the past twenty years in this country became more acute as I thought more and more . . . not only about who I was and what my family was in the early 2000s and ’90s, but about where the country was. The rise of Trump and this right-wing, xenophobic, populist politics of division really begins in 2001 with the reaction to 9/11 and [with] the Iraq War. It’s not a movie that’s trying to make a statement about the end of the Cold War, either, but this is implied in the values of the characters, especially Richard. His concern with money is pretty obsessive. He has a poor relationship with his in-laws out of fear that he isn’t living as comfortably as they do. We see him exchanging bills and writing checks, applauding the closing of the New York Stock Exchange bell. This is all happening at the end of “greed is good” and the dawn of unlimited peace and prosperity, which I think, in hindsight, is not something that has aged especially well, now that there’s a war in Europe and inflation is near the double digits.

CL: You include news footage in quick, impressionistic bursts, which feels true to how a child might become aware of the larger world through TV. How did you decide when and where to use these clips?

RD: When I wrote the script, I relied on two timelines. One was a chronology of my family history, and parallel to that, there was a historical timeline. It was based on the principle of: What is it that I remember seeing on television, or hearing the adults in the room talk about? What was it that seemed, as a child, quite strange? Seeing [footage of] people in the snow coming out of a building with soot on their faces—I didn't know what the World Trade Center bombing of ’93 was, but I remember seeing the people being carried out.

These are things that are somewhat impersonal: the sense impressions of a child, like things you can put in a memory box. I don't mean to say that every bit of archival material comes from that nebulous storehouse of memories, but certainly, most of it does. That’s why I think The Mirror [1975] by Tarkovsky was important for me to think about. In that case, it’s the intrusion of Soviet history through newsreels onto this chronologically scrambled story of someone recalling his childhood from his deathbed. But these moments aren’t just there to give a chronology of the times, or to editorialize. Otherwise, I could do, you know, an Adam McKay movie.

CL: I was also interested in the way you depict the perspective of an only child—there’s that line about how Jesse is carrying these memories of his family that only belong to him, with no siblings to remember them too. He’s also quite solitary at family gatherings, which are crowded with lots of adults, and we don’t necessarily see him around peers as he gets older.

RD: Jesse is a kind of observer. He functions in a way that’s not too dissimilar from the way that the narrator functions. Yes, he is a member of the family, but he’s almost like a single-person Greek chorus, kind of spectral. We don’t know what he’s thinking and feeling at any given time. Really, the only time he speaks at length is during the classroom presentation of the photograph [of his aunts]. He becomes, at that moment, an educator for how to view the movie. He articulates a lot of what the film is trying to do. When we see the epilogue of those two women on the bed talking, we realize that this is something that Jesse may have had some memory of, at perhaps the last moment this family was together. It’s tied into a teenager's memories of how the light entered a room, how he will always remember the windows in his father's apartment. I don’t want to say it's him finally acquiring a voice or something, but the character is so silent up until then . . . There's all this knowledge being stored about the rooms he's moving through, the people he's seeing. And at that moment, he's allowed to give voice to all of the stuff he's been seeing.

CL: You worked with a larger budget for this film and a cast of professional actors, and all the while, you maintain the same deliberate aesthetic of your earlier work. Did the production conditions have any effect on your stylistic choices?

RD: I don’t think me and my producer, Graham [Swon], could have made the movie under the circumstances that I made my other films. It's an ensemble film, it spans twenty years, there are many, many locations. The budget was about $200,000, which, considering that my first feature was made for under $30,000, was like having a film studio. I remember going into Light Industry, in Greenpoint, where we did the costume fittings, and seeing racks and racks and racks of vintage clothes organized by character by the wonderful costume team. This was something that I had never contended with on previous shoots, and having the money to do this with a dedicated crew was lovely.

This also allowed me to work with the actors in a way that I couldn't before. Previously, it was: Here are some friends, and they’re going to be in my movie. Maybe they’ve done a bit of acting, but they’re mainly doing it as a favor. As a consequence, their performance is going to display a limited repertoire of tones of voice and gestures. One could point to all kinds of precursors for that under-psychologized performance style: Bresson, Brecht, Straub-Huillet. But these new actors were professionals who thought carefully about what they did. It would have been imprudent to impose something on them that they didn’t think suited their performance. Hence, the performance style in The Cathedral is less controlled than in my previous films. I think the film benefits from that, especially with the father, Richard. I wasn't going to tell Brian d'Arcy James, “I'm going to give you a line reading, and I want you to read it that way.” His intuition was right. Someone like that needs to be expressive; I didn't want to make the character just a jerk.

CL: I’m always curious how those choices change with new production contexts, since filmmaking is such a practical, putting-out-fires kind of art form.

RD: I try to prepare as much as I can beforehand. Before we hired a costume designer, I had created a digital archive of hundreds of scanned photographs from my childhood, even digitized VHS tapes of my parents’ wedding and my third birthday. These could be indexed and accessed by people working on the film; hair and makeup could see the length of the women’s nails for early scenes. We also shot in my dad's apartment, where I grew up. The interior hasn’t changed very much since 1988, with the exception of the entertainment unit and a new couch—he actually got that pale pink, Miami Vice couch three years ago, not in 1990. But the period was already intact.

CL: What was it like to bring a film crew into his apartment?

RD: There was never a moment in the four or five days we shot there where I could reflect on that. I was so preoccupied with other things, the stresses of shooting. But right before moving on to a new location, when we had just cleaned everything up. I just thought, how incredible to have spent five consecutive days in this place, which has a very special meaning to me, with people who have no relationship to the space or my childhood, summoning things that I remember. It’s not a natural thing to have to witness a re-enactment of a Christmas Eve in 1988, in which all of these people are there, some of whom are now dead, but they are dressed in costumes that are nearly identical to what they wore at the time, in that same room with the same furniture.

Even though it shows up in the film for maybe thirty seconds, that shot went on for ten or eleven minutes before I called “cut.” They had a number of gifts that were wrapped, and the idea was that they would open them for a minute or two, but then I thought, why not let them open them all and do the whole take? It was surreal for me to sit with the monitor and watch this, with the boom operator and the lights set up. It dawns on you late that this kind of thing is pretty extraordinary and will never happen again.

CL: You’ve said that your short films are miniature ways of working through aesthetic problems. What sorts of aesthetic problems are you drawn to? Was there anything that you wanted to investigate in this feature?

RD: I think each film is a problem that I try to solve in some way; I try to deploy different strategies. In this case, the problem was making a movie about an American middle-class family in the suburbs outside of New York City. How does one convey a family coming undone over a number of years without making filmed theater? Without making American Beauty [1999] or Boyhood [2014], or a movie in which you have characters around a dining table shouting at each other?

It was important not to have an argument in the film. There are the ends of arguments—I mean, hell, Richard throws a remote control at a wall and Lydia leaves. That is probably as much explicit drama as you’re going to get in The Cathedral. But I didn’t want the content of the film to dictate the form. There are so many touchstones for making a movie about an American family; it has such a heritage in literature and drama. What could I do so that I wasn’t doing what received notions may have been seducing me to do?

The Cathedral screens on April 29 at the Museum of Modern Art as a selection of New Directors/New Films 2022. Director Ricky D’Ambrose will be in attendance for a Q&A.