Frederick Wiseman’s Near Death (1989) opens with a montage of Boston: scullers rowing along the Charles River, billboards perched over traffic on a two-lane road, and then a wide-shot of the Beth Israel Hospital. In under two minutes, viewers are brought from the city’s riverbanks, right onto the doorstep of one its most vaunted public institutions. The camera makes its way through the building, starting at the driveway where an elderly woman is being wheeled out of a car, to the lobby as receptionists take calls and redirect visitors, and finally to a door with a sign reading “Pulmonary/Medical ICU Authorized Personnel Only.” It is from this floor—the endpoint for many Bostonians—that the veteran documentarian engages in one of the most revelatory surveys of American life.

Along with an ensemble of nurses and physicians, Wiseman takes the viewer up close and personal with four patients during their final days. Some may have months to live, while others are dangerously teetering on the verge of death. We sit patiently, either by the patients’ bedside or in the outside hallway, immersed in the disturbingly serene soundscape of the annex. The chatter of the staff is gradually drowned out by the droning whirs of the ventilators, the periodic beeps of heart rate monitors, and the hisses of air being drawn in-and-out of cavities via a network of plastic tubing. It’s these moments of contemplative silence, as families gather around loved ones or while attendants clean out a newly vacant room, that Near Death is heaviest.

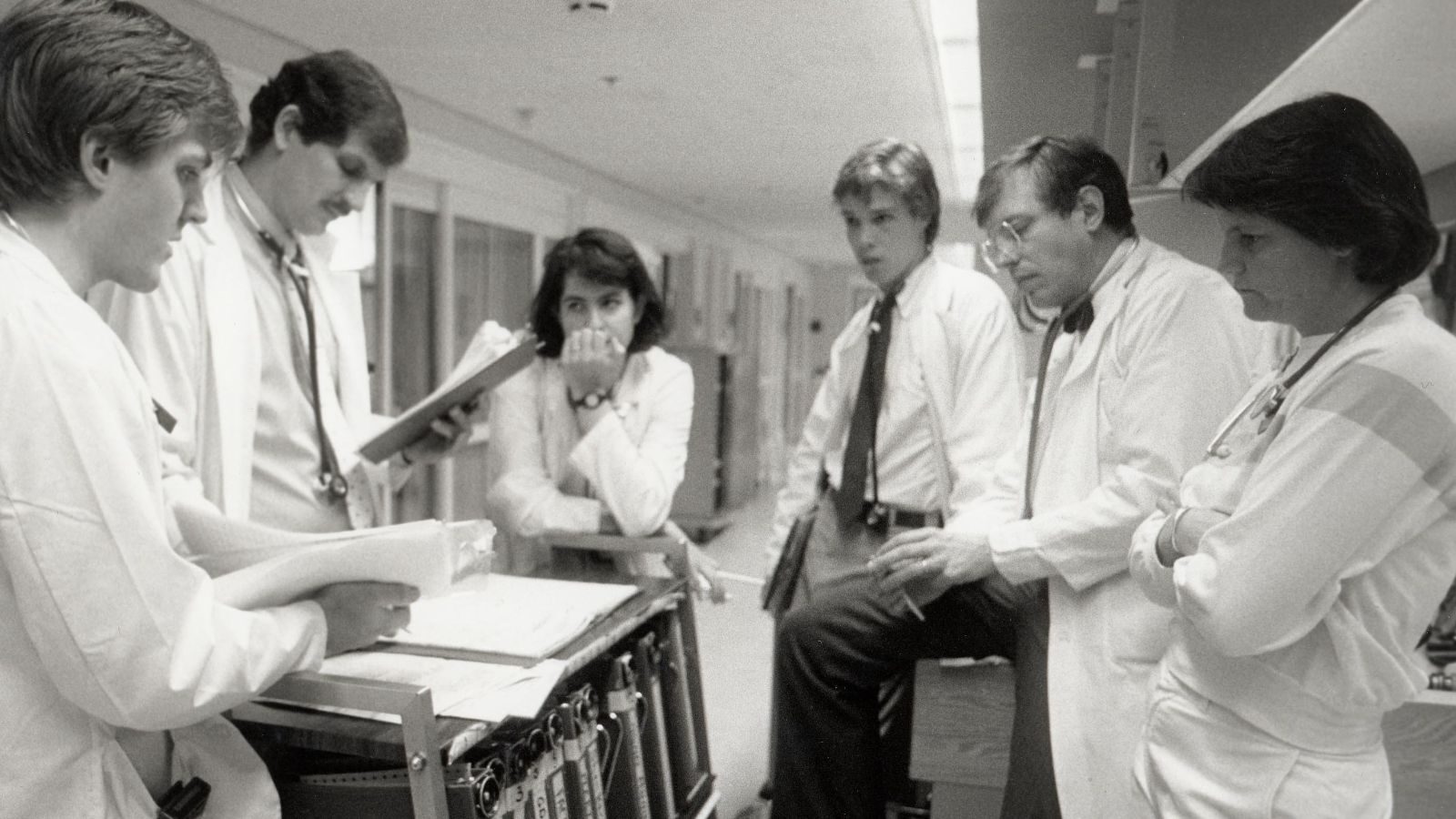

For newcomers to Wiseman’s oeuvre, the film’s 358-minute runtime may feel intimidating. How many minutes of watching life slipping away are we expected to stomach? However, reckoning with mortality on an emotional level only forms half the picture. Despite being entirely set in an ICU ward, the film rarely feels clinical or tedious in its approach. While Wiseman’s Hospital (1970) depicted the often chaotic process of preserving life, here the staff’s goals are not to cure, but help find the most “comfortable” way out. With do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders having only been introduced a little over a decade before Wiseman made Near Death, his film shows how overworked foot soldiers of the healthcare system were tasked with the burden of navigating an ethical minefield. As one physician points out in a meeting, “we controlled when we let the person go.”

Much like his other works about the United States’ public institutions, Near Death examines how people navigate these complex structures, carefully filming the roundabout processes of mediating consensus. But unlike The Store (1984) or Central Park (1990), Near Death is not about the institutional worlds that govern the rhythms of life, rather the one concerned with negotiating death. Legal experts and medical schools may postulate their own criteria for biological death, but Wiseman is more interested in dying as a social process. With a patient’s cognition rapidly deteriorating, it is often up to healthcare workers to reason among themselves, and with family members, on the best course of action. Or, as one doctor bluntly puts it, life can be carried out “in an institution with a tube in your throat, or you could die tomorrow.”

Near Death screens March 4, at Film at Lincoln Center as part of “Frederick Wiseman: An American Institution.”