The “Netherworld” film program organized by Melissa Lyde, of Alfreda’s Cinema, in collaboration with Dr. Rizvana Bradley features work by Black female directors. The series is an ode to the ongoing conversations among Black female filmmakers and artists, responding to cinema's capacity to reveal the wounds of the past, while simultaneously interrogating the ways cinema has played a key role in the making and maintenance of a racial regime of representation. Dr. Bradley has been interested in how Black experimental media and moving image cultures have been evolving against the grain of film—its racializing force and function as a technological medium—and has centralized Black women’s artistic production in her research and writing. Lyde has done the same in New York film programming. The series they have collaborated on foregrounds the singular impositions and constraints with which Black art has to contend, and celebrates Black women’s creative interventions, exemplified by the films they’ve chosen to show on-screen.

Dr. Bradley’s book, Anteaesthetics: Black Aesthesis and the Critique of Form, reads with and against modern and contemporary artistic mediums, including film. It redeploys their archives toward anti-reparative ends. The films in the “Netherworld” program are all in conversation with Anteaesthetics, exploring cinema's relationship to both the erasure and distortion of Blackness on-screen, particularly as this pertains to Black femininity, the movement of history, labor, and reproduction. “Anteaesthetics is a book that emerged from my sense that we are desperately in need of new methods and vocabularies for confronting the complicated relationships between Blackness, anti-Blackness, and the aesthetic,” Dr. Bradley said, in a conversation we shared over the phone. Bradley’s work is indebted to thinkers such as Simone Browne, Huey Copeland, Aria Dean, Kodwo Eshun, Michael Gillespie, Kara Keeling, Louis Chude Sokei, Jacqueline Stewart, and many more scholars who have problematized conventional understandings of Blackness, the cinematic medium, and race and technology more broadly.. The “Netherworld” film series that stems from Dr. Bradley and Lyde’s relationship to the topics discussed in Anteaesthetics poses a crucial question: how might a screening, a gathering, or a conversation amplify the difficult philosophical questions posed by Black intellectual and artistic traditions?

Melissa Lyde and I talked about this over the phone this past weekend. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Lucy Sternbach: You are programming two back-to-back screenings this week. “Netherworld” will screen at BAM and dream hampton’s It Was All A Dream (2024) at the Brownsville Heritage House. When we talked about the “Nolly Babes Film Festival” last November, you mentioned that when you started Alfreda’s Cinema back in 2015, you wanted to find a permanent space for it in Brownsville.

Melissa Lyde: Brownsville has a special place in my heart as my ideal location for Alfreda’s Cinema. In visiting the Heritage House, I learned from them that Brownsville actually used to have 26 Loews Cinemas—beautiful, art deco, landmark cinemas. They’ve all been converted for alternative uses now, but Brownsville used to be a place for filmgoing. It's an impoverished community that’s been left to the wayside of politics and the city’s economy. It’s starving for arts and culture. There are organizations focused on the immediate needs of the community addressing gun violence, petty crime, malnutrition, low education rates… There are soldiers on the ground in that community, but it's obvious that nobody is coming in to help us, so we have to help ourselves.

I don't live far from Brownsville. I'm just a few blocks away and growing up in Brooklyn, I knew that Brownsville was not the place to go. Brooklyn really wasn't the place growing up, but Brownsville was like the scary, scary neighborhood. What I love now about Brownsville is that it's still majority Black. It's kind of protected by this notion of a criminal element, and it's odd that that’s what has protected it the most from gentrification, even though it's coming. It’s on its way and in about 10 years it won't look the way it looks today. I want to jump in before that really gets rolling, and at least build a space that is aiding and preserving the community's core demographic, and partnering with an organization that's already doing that. Brownsville Heritage House was started by Mother [Rosetta] Gaston, who was a self-taught archivist. She was a woman who collected the city's records, or items from neighbors, and she built this beautiful archive, very much like Arturo Schomburg. I found out about the Heritage House on a Tik Tok video and a week or two later, I showed up and said, “I would love to start building a community of cinephiles in Brownsville.”

LS: When did you first go to the Brownsville Heritage House?

ML: Over the summer. We started to talk about the possibility of doing a film program and they said that they hadn't had one since 2015. I figured it would be nice to restart something now that we're out of lockdown and people might be more open to traveling there to experience something new.

LS: I’d love to hear more about your film series at BAM. What was the curation process behind connecting the four films in the program?

ML: I had been following Dr. Bradley's recent publication release, Anteaesthetics, and I had asked her if she was going to be doing any speaking engagements in New York over Instagram—I slid into the DMs. I had long admired Dr. Bradley's work, since Simone Leigh’s “Loophole Of Retreat” Conference in 2018. I was really inspired by her reflections on Black culture and Black art. They started to make me think about the possibility of going into higher education, or looking into it as a next step. It never really came to be because I'm not interested in acquiring anymore debt, but that didn't stop me from being a student from afar. That's kind of what I consider myself now, one of Dr. Bradley’s marginalized students—the women who buy her work, read her essays, think about, and follow the work that she does outside of academia.

The works that we've compiled are specifically single channel installation pieces. It challenged me to bring in a format that doesn't normally get a theatrical experience. I love that challenge because I'll go into these art spaces, I’ll see these works, and I'll be just like, “Man, I wish I could see it so much bigger, like, really be in it.” This was my opportunity to do that, to be immersed in the world of those films that are larger-than-life. And most of the films came through relationships that I had built with the filmmakers over time.

Andrea Kindred’s Sunrise Awakening [1975] is a beautiful portrait of Black Australian, or Aboriginal, relationships in the ‘70s. For me, that was kind of the best example of what Dr. Bradley and I were expressing: work that's born into space, what she coined “Netherworld,” the underside of mainstream culture. We’re born marginalized and born into another space. These are artists who create for the sake of creating. They know that they're probably never going to be platformed, but they make art anyway. That’s what a lot of Black artists are forced into: to make work in obscurity.

LS: With Corinne Spencer’s work there seems to be a concern with what constitutes a body. Can you talk about the specificity of her work?

ML: I saw Corinne's work last summer at the Governor's Island exhibition, but I had started following them well before then. They were doing these ethereal exhibitions and it just came across my timeline. Usually, Corinne's work is projected on these silk screens, like giant silk cloths. It's like waves in the room—these white, transparent silk cloths. And then her visuals are projected on that. To include Corinne here is such a privilege. It was such a great opportunity to finally bring her work into the film space and it felt right because this is still someone's imagination. You’re seeing how her creativity is exploding in this medium, which is this “netherworld.”

LS: I noticed that the program that you and Dr. Bradley put together includes filmmaking practices that span 50 years. Most of them are contemporary, but you also bring the audience back into time with Sunrise Awakening.

ML: People don't realize that this is how Black women have been making art since the dawn of time—this underworld, creating space for themselves, making a way out of no way. We see that with Kindred’s film. I could never have thought about this convergence of Black American culture in Australia. These people are defining themselves as Black—and they don't need to do that, because the Australian Aboriginal culture is so beautiful and rich. But they embrace this Black American terminology because they see a shared disposition, a shared struggle. This helps them recognize the pride of being Aboriginal. I love this marriage of the two cultures there.

LS: I think this film is an interesting one to open with. How did you come to Kindred's work?

ML: I came to it through a friend, a co-conspirator in film programming. We were both programmers at the Dunam South African Film Festival. She’s a Black woman, a Black and Aborigine woman working in Paris. Greta Morton. She posted an image of this film about a year ago on her Instagram and I was like, “What the hell is this?”

I sit on films because I'm constantly collecting them and putting films in little cubbies and storage folders in my brain. Then, I'll come back to a film when I'm ready to program it, or when I've come to a place where I can program it. I don't have every film at my fingertips. This is the hard way of programming, but I just get interested in a subject, research that subject, and go into this real rabbit hole of research. I just find things in this black hole that I'm in when researching a subject. I become insatiable. I spend so much of my time just watching what other people are doing. Isn't it weird… I mean, I'm a voyeur. That’s just how I put my work together.

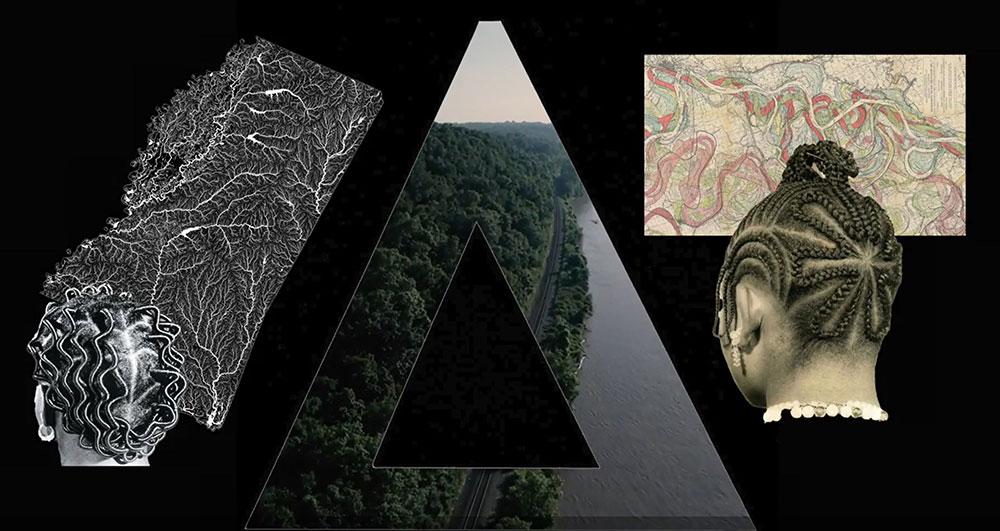

I also came across Zion’s film, 2,340 miles from 1880 [2023, pictured at top], through Instagram. I've been following Zion and Black Discourse for at least a couple years now. They posted that they had a film and I commented, “I want to watch the film.” I admire their art on Instagram and they sent me a link. I was blown away. I actually programmed that film ahead of our Juneteenth screening at Rockaway, alongside Black Chariot [1971].

Revisiting the theme of this program, I wanted to show it again. I knew that was the kind of film that everybody needed to see. It just rocked me. All of these films do that. You know, Ina Archer had such a beautiful summer with her recent exhibition To Deceive the Eye [2024]. And Ina is the film programmer's programmer, like the DJ’s DJ. She’s probably the best and most skillful creative Black film programmer I have ever known. I'm so floored by them. On top of that, she’s an incredible mixed-media artist.

The space they created with Black, Black Moonlight: A Minstrel Show [2024] really disarmed blackface—she’s almost like a superhero. She makes it so much more palatable for you to experience it, because, in so many ways, it is absurd.

LS: What’s Archer’s relationship to minstrel and blackface, and their representation on-screen?

ML: Nobody is addressing blackface and minstrel. During a conversation she had at Microscope Gallery, I asked her, “How do you perceive or how do you receive blackface?” That was my question to her, because for me blackface has always been a personal trigger. It's something I never wanted to see. I hate seeing my ancestors degraded in this way, but then again, you put yourself in their shoes and ask yourself, “What would I have done?” Would you want to be sharecropping or would you put on some fucking dark makeup and do the jiggle? These were people's fucking means of making a living.

Watching Ina’s show, it became beautiful, it became humorous and provoking. I love the way that she embraces minstrel with satire and humor. I love Hollywood cinema and I love that she loves it too. I'm a Black film programmer, but if there's a Robert Mitchum film, I'm watching it, and it's because the writing is so good, the acting is so good, the cinematography is so good—it's top tier artistry. We’re all victims of white patriarchal supremacy, but that doesn't mean that I can't be entertained by it at the same time.

LS: I was also interested in how she moves us between entertainment in the so-called informal space of politics and into footage of this debate between James Baldwin and William Buckley. I'd be curious to hear more about how her work informs how we also think about the audience differently in filmmaking practices in general, but also in how she's also harnessing an awareness of the audience.

ML: She's admitting that the images that she's manipulating are all of entertainers. In a way, she's entertaining. I feel like she puts that on its head and that's kind of the question that she asks in her work: “Is this really entertaining you?” She does it through this graceful, absurdist humor. You laugh to prevent yourself from crying, but you know that we have all been subjected to white supremacy, that it's both degradation and entertainment.

LS: How do you see Ina’s work in conversation with Zion Estrada's work, which addresses a slave revolt in 1880?

ML: It’s so much about preserving people and stories, because there are people that were never asked about their experiences in America. Zion addresses a slave revolt in 1880, 15 years after the Emancipation Proclamation. There was a 200,000 person slave revolt that was allegedly executed without a single death. Her film speaks to that and then it goes into this really beautiful demonstration of the Army Corps of America.

She actually drew from the life of Mitch McEwen, her co-director, who found these letters by her great grandfather speaking about this labor. Zion then worked to really investigate this. She beautifully displays the unfolding of this action, and speaks to the environmental harm of displacement for these people who knew their land. That really echoes with how Hurricane Katrina pretty much demolished New Orleans, because the people who knew the earth were no longer there. They were displaced by gentrification, by the construction of the levees. And people who were inept—engineers, construction workers, servicemen—were tasked to build these levees and redirect the actual water flow of the Mississippi Delta. That essentially led to a catastrophic event in 2005. So, Zion takes on a huge task in the 12 minutes of her film. And she does it with such beauty and such a graceful, sharp editing practice.

This film had only really been seen as part of an installation with the Black Reconstruction Collective. This is the first time it'll be shown inside a theater. I'm really proud to be able to premiere the work and to have Zion in attendance. I think she's just such a powerful filmmaker. Ultimately, I can only interpret what my own experiences with it are, or have been.

LS: How is Zion harnessing the idea of going against the system and across time?

ML: Ultimately, I selected these films because I felt like they had built up their own world. Zion has these materials from Mitch and she starts to do her own investigation. To uncover all of this, she actually procures evidence from the Army Corps of America's construction of the levees. There really isn't any available footage that captured that, but she managed to find it, which is incredible.

I have to say that it is of its own world, because it's proving that, despite not having the apparatuses of mainstream investigative journalism, she's creating a text behind this slave revolt that I've never really heard about until Zion made a film about it. 200,000. Again, 200,000! That's a lot of people! 200,000 formerly enslaved Black people living in America that organize themselves to have a slave revolt. These people are still operating within the confines of slavery, 15 years after 1865.

LS: She’s digging up the way the media decentralizes or removes this history?

ML: Right. History removes, history ignores. But it's the truth and the truth is not what's taught. We have to reckon with that. We have to continuously acknowledge that we are not being told the truth. We essentially don't learn this history, but we do learn about Nat Turner's rebellion. We learn about rebellions that occur and fail. This was successful. This was a success because nobody died. We learn about the rebellions in which thousands of Black people were slaughtered, but we don't learn about Denmark Vesey. Vesey had organized people in Tulsa, South Carolina, to confront the white supremacists who were enslaving them. There could have been a mass murder at this moment, but his efforts were spoiled by insurrectionists. We don't learn about him and people don't talk about him because they don't want to talk about the effective way that he did organize.

LS: Zion is bringing that silenced history to us through a very visceral experience, tying it to the human body, the body of water, and movement.

ML: Sound and audio are huge components in Black and African cultures. We are hugely oral people. We create music and we create noise that is described as music. For the most part, Zion is a sound artist. In this film, she uses sound as a means of time travel. We are traveling through time in her film. In my conversation with her, she said, “You can never enter the same body of water twice.”

LS: To bring it back to what you've been doing, what evolution has your curatorial work undergone since 2015?

ML: A lot of people are responding more to the short film programs that I do. They see a style that I'm giving to that particular way of programming. I have the ability to really just dig into the vaults for short films that don't normally get their theatrical moment. That's where I get to be the most creative. I’m not speaking to any linear theme. I've been so elated that people are responding to that.

Our first program at BAM was a selection of Black shorts that spoke to the work of bell hooks. We sold out the largest theater. I have never seen Black archival shorts selling out a cinema. I'd never seen that in my years going to BAM. I've never seen a shorts program selling out their largest cinema. I have to say that I'm sure bell hooks helped, but people gave them as much love as a feature film.

LS: As a final question, I wanted to ask you what kind of hurdles you've been running into in terms of your curatorial process and your communication with filmmakers and audiences?

ML: It always comes down to money. I still feel like people don't necessarily want to pay a Black-operated space the same that they would pay to get into a white-operated space. It’s no problem to pay $15 to go see a film at Lincoln Center or Film Forum, but I think it's harder to get audiences to pay a $15 ticket at a space in Brownsville. But that space needs that ticket price more than BAM does. But again, BAM is also not receiving the same kind of funding as other art spaces in the city.

I still feel like in the city, film programming is not funded. Well, it's not funded in the way that visual arts or performing arts are funded, and it's not fair. This stuff draws in a crowd and it needs to be a part of our language and cultural arts as much as everything else. It's not fair to ask people to pick and choose what's more important. I love performing arts, but that's not where I think I'm most at home.

“Alfreda’s Cinema presents Netherworld: The Anteaesthetic Experiments of Black Women” takes place this evening, September 26, at BAM. Author Rizvana Bradley will be in attendance for a Q&A.