Shifted from its typical spring dates, New Directors/New Films 2020 launches today in an online edition running through December 20. The annual partnership of Film at Lincoln Center and MoMA, now in its 49th edition, is dedicated to presenting bold works by early-career filmmakers, and is a great survey of often under-the-radar works from other international festivals.

This year Screen Slate is providing short critical takes on films throughout the festival, starting with these four from Josh Bogatin, Jeva Lange, and Chloe Lizotte. Stay tuned for more!

Boys State (Amanda McBaine & Jesse Moss)

Jesse Moss and Amanda McBaine’s Boys State focuses on a Texas summer camp wherein one thousand early teen boys gather for a week to simulate the American two-party electoral system through constant bickering and juvenile tactics. While this might sound like the perfect Lord of the Flies fever dream to represent our psycho race to communal doom, Moss and McBaine’s overserious approach to the material, replete with moody low-key cinematography and rote inspirational music, leave it feeling little more than mechanical.

The drama centers on a gubernatorial race fought between Steven Garza, a first generation Mexican immigrant adept in both-sides-of-the-aisle centrism and humble-brag rhetoric, and Ben Feinstein, a media-savvy political junkie and double amputee who dishes out firebrand, far-right one-liners and catty memes with aplomb. As the candidates hustle their way through primaries, stump speeches, and talent shows, the pressure and emotional strain build along with the obvious Obama/Trump parallels.

As Ben extolls his running mate’s killer looks and Steven uses his own humble origins to compare himself to Napoleon, what feels surprisingly absent from the film is any acknowledgment of the actual stakes behind democratic decision-making. Perhaps the film’s most insightful moment comes inadvertently through Steven’s primary challenger, Rob, a well-intentioned jock who proudly believes in nothing and pumps out the asinine slogan, “Vote for someone! Vote for Rob!” If only our national politicians could be so pithy and honest in their own assessments. (Joshua Bogatin)

Los Conductos (Camilo Restrepo)

Partly based on lead actor Luis Felipe Lozano’s real-life escape from a sinister religious sect, Los Conductos turns memories into molten material. In a darkness slashed open by flashlight beams, Pinky (Lozano) abandons a cult — and a murder scene, suggested by a bloodstain on a jacket — for the Colombian city of Medellín, where he hides out in a lonely warehouse and finds work printing counterfeit t-shirts. But in poetic voiceover, director Camilo Restrepo threads through Pinky’s recollections of his cult’s “father,” who taught his group of marginalized outsiders to seek revenge against the society that discarded them.

This message haunts Pinky as he seeks to be resurrected — again and again — as an emblem of festering social ills. His psychological fracturing is as fiercely textured as Guillaume Mazloum’s 16mm cinematography (Restrepo himself is a member of L’Abominable, an artist-run film development lab in Paris): Pinky might narrate a story while the camera, affixed to the front of a motor scooter, bombs through a harshly lit highway tunnel. Restrepo weaves in a closing reference to the Nadaísmo poetry movement of the 1960s, which called for the rejection of social order; even if the endless Adidas logos of Pinky’s t-shirt factory are surreptitiously counterfeit, they represent the capitalist forces that continue to hold the cards. But as Pinky weaves his way through the city — equally tripping out on flashbacks and the crushed bricks he smokes by night — his nimbly shifting forms eclipse the limitations of his solitude. (Chloe Lizotte)

Days of Cannibalism: Of Pioneers, Cows, and Capital (Teboko Edkins)

Teboko Edkins’s Days of Cannibalism: Of Pioneers, Cows, and Capital is a collective portrait of the town of Thaba-Tseka in Lesotho and a diagram of its changing economic hierarchy. We meet impoverished cowherds, bored cops, pathetic cattle thieves, cruel judges, and ruthless Chinese capitalists who have recently risen to control the town’s commerce. The contrast between the Chinese expat entrepreneurial class and the native Basotho people is stark; while the Basotho wrangle oxen, the Chinese discuss their choice of architects and wear Bluetooth headsets. Small surprise that there’s resentment among the locals, resentment that eventually turns violent.

Days of Cannibalism is a hybrid doc, or, in Edkins’s words, “controlled reality.” For the most part we get a formally restrained observational documentary — a static camera recording either a series of small transactions in the market, the anti-Chinese rants of a DJ at a local radio station, or the trial of two unemployed men in the District Court of Thaba-Tseka — but the movie is theoretically a Western, a tale of a frontier that still has a malleable power structure. It is also an Animal Crossing-style illustration of the most basic principles of commerce, a sort of Adam Smith in Africa. And since cows may be the purest form of capital — just look at the etymology of ‘cattle’, which derives from the Latin ‘capitālis’ — we might be learning something more essential about primitive accumulation than we would if grain, gold, or land were the commodity in question.

Of course, the Chinese are not the first to colonize Lesotho. The British were there from 1869 to 1966, followed by “soft” colonization by Euro-American commerce. (I spotted brands like Bic, Halls, Adidas, Nokia, Rizla — even Supreme.) But to me the most fascinating trace of this cultural colonization is the frequent appearance of English words in the Sesotho language. For example, everyone refers to quantities in English. Why? Sesotho has its own number words, so why do the film’s subjects all use English to count? And why are the town’s only visible businesses called “Meat Talk Butchery” and “Food Talk Restaurant”? Is there some kind of shanzhai effect happening here, accidental poetry born of broken English? (Cosmo Bjorkenheim)

“Love is a feeling,” says one of the characters in Robert Machoian’s The Killing of Two Lovers , which situates such emotions as unwieldy tidal currents. Set in a remote town in Utah, where Machoian is based, the film takes a present-tense approachto its story of a trial separation between David (Clayne Crawford) and his wife Nikki (Sepideh Moafi). David, a handyman whose face seems buried under an armor-like beard, struggles to reach back out to Nikki while looking after his aging father; meanwhile, Nikki cares for their teenage daughter Jess (Avery Pizzuto) and three hyper boys (Machoian’s own kids). To David’s repressed dismay and anger, Nikki also starts quietly seeing her law-firm coworker Derek (Chris Coy).

Instead of peeling back layers of backstory to find a tipping point for their marriage—although it’s not a stretch that falling into a relationship at seventeen might prompt reflection, four kids later—Machoian is more interested in who both characters are in this moment, and whether or not their mutual respect could mature in order to survive. He and DP Oscar Ignacio Jiménez turn the emptiness of the landscape into a sort of straitjacket; if the film’s opening close-up of David—gasping for breath, clutching a pistol, while watching Nikki sleep soundly next to Derek—boxes him into a claustrophobic panic, his short path back to his father’s house looks equally constrained within wide-open vistas. David’s unvoiced rage, thrumming within intricate PTSD-ish sound design by Peter Albrechtsen, builds a bit of a familiar tension, but the winding, desperate conversations that David has with Nikki and his children are riveting, and always threaten to come unglued. (Chloe Lizotte)

The Mole Agent (Maite Alberdi)

There has been a disconcerting amount of talk this year about the worth of the elderly — a dismissal of the seriousness of the pandemic on the grounds that it primarily kills the very old, and that grandparents are worth sacrificing to save the economy. That already ghoulish line of thought is only made more monstrous by the touching documentary The Mole Agent, which — while having nothing ostensibly to do with our "current moment" — has everything to do with the overlooked value of senior citizens, whom far too many of us are more comfortable keeping safely out of sight.

In Maite Alberdi's film (although "experiment" might almost be a more appropriate word), 83-year-old Sergio Chamy is hired by a private investigator to infiltrate a nursing home in Santiago, Chile, for several months in order to look into allegations of abuse by the staff. The residents of the facility are told that the cameras in their home are there to shoot a documentary that primarily focuses on Sergio, so as to not arouse their suspicion. Admittedly, the premise is ethically questionable, but what results is a moving, bittersweet portrait of Sergio's friendships with the (mostly female) inhabitants of the nursing home, many of whom seem to have been conveniently left there to be forgotten by their families.

"The residents here feel lonely," Sergio reports back to his boss at one point. "They aren't being visited, and some have been abandoned. Loneliness is the worst thing about this place." Though The Mole Agent seems, at least at first, to be playfully asking, "what if James Bond, but 85?", the result is more a meditation on growing old when a family — or, perhaps, a nation — finds you disposable. (Jeva Lange)

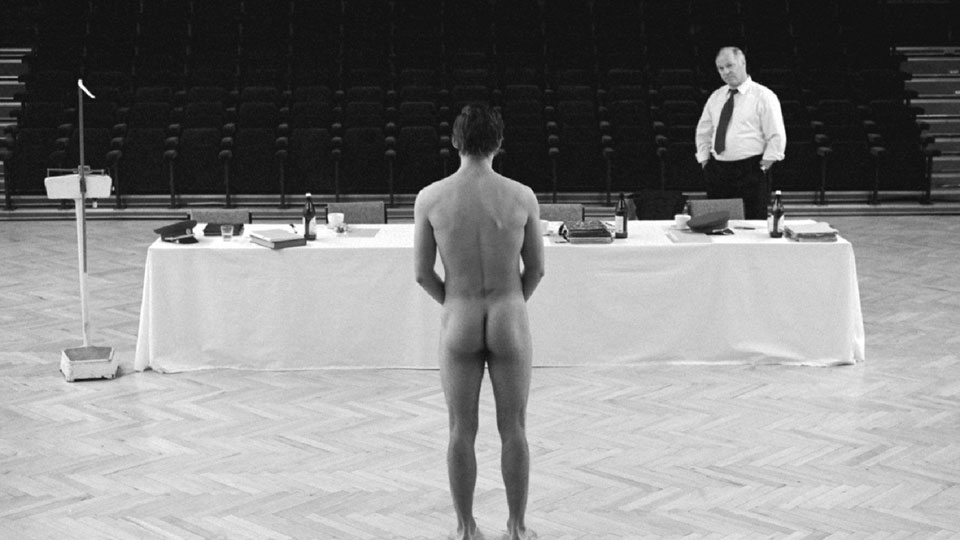

Servants (Ivan Ostrochovský)

Ivan Ostrochovský’s Servants is an anti-Communist thriller set in a Czech seminary in the 1980s. Cinematographer Juraj Chlpik’s high-contrast black-and-white images and composers Cristian Lolea and Miroslav Tóth’s dissonant score set a tense, oppressive mood for a tale about teenage seminarians grappling with their consciences under the watchful eye of a totalitarian government; In the Name of the Father meets The Lives of Others or Costa-Gavras’s The Confession.

In 1971, an organization of Catholic clergy loyal to Czechoslovakia’s Kremlin-controlled Communist Party, named Pacem in Terris, was formed to solidify the collaboration between church and state. Clergy members opposed to the regime began meeting secretly in basements, and the Státní bezpečnost (State Security) started a campaign of intimidation and torture to smoke them out. When the events of Servants begin, we’re a decade into this process, and the situation’s hopelessness is legible in the deeply lined faces of the older priests who run the clandestine reading groups, such as Father Coufar (Vladimír Obsil), who eventually turns up in a ditch—broken-limbed, facially mangled, and dead—after an “accident.” The teenage seminarians are less shook, at least to begin with, thanks in part to their lack of experience with the cruelty of State Security’s goons. Juraj (Samuel Skyva) initially outdoes his bestie Michal (Samuel Polakovic) in his commitment to the cause of spiritual freedom, but Michal is not as obedient as he seems.

Servants revels in its stunning 4:3 black-and-white compositions: a cemetery with smokestacks of Communist industry looming ominously on the horizon, like giant tombstones for a moribund civilization; a game of soccer in a tiny courtyard shot from directly above, like a grayscale Breakout; a pool of blood spreading almost symmetrically across the bottom of a top-bunk mattress, like a gory Rorschach test. The score contributes to the austere atmosphere; it is largely composed of textural, atonal horns, imparting an unsettling atmosphere a bit like György Ligeti’s “Requiem.” It represents the more restrained side of Tóth, whose other work includes the “free improvised electro-acoustic avant-core music project” Shibuya Motors and “pure free-jazz saxophone evil” collaboration My Live Evil, which seems to more in common with Naked City than with Ligeti. (Cosmo Bjorkenheim)

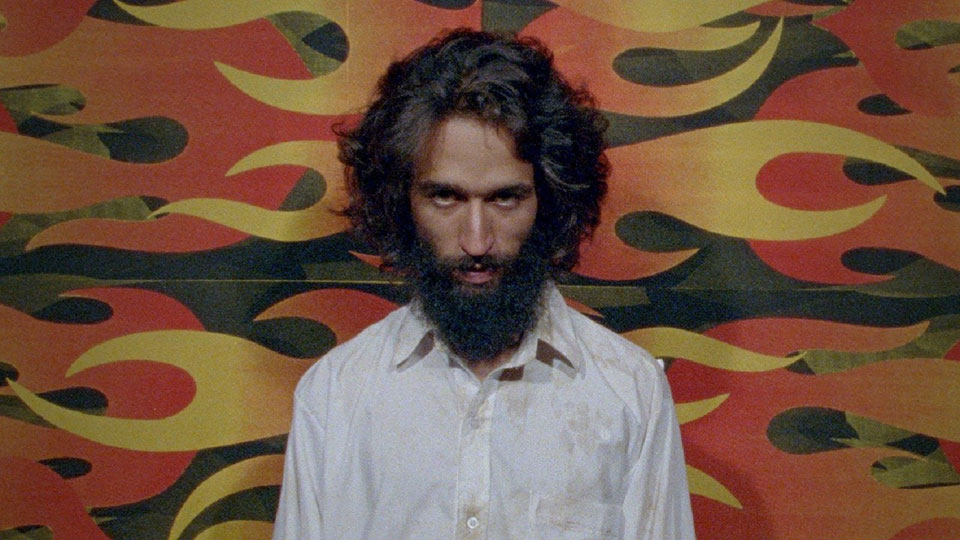

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (Pushpendra Singh)

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs is exactly the sort of unexpected gem that makes New Directors/New Films a delight year in and year out: based on the poems of a 14th-century Kashmiri mystic, it tells the story of the nomadic bride Laila (Navjot Randhawa), who migrates with her shepherd husband Tanvir (Sadakkit Bijran) to the high pastures of the Himalayas, only to catch the eye of the local ranger, Mushtaq (Shahnawaz Bhat). Though there is a political allegory at play here — Laila's beauty and fierce independence, coveted by the two competing men, draws a parallel to the stunning natural landscape of the Indian region of Jammu and Kashmir, which is contested by Pakistan — the register of the film is far more folkloric. Structured by the seven traditional songs referenced in the title, such as the "The Song of Marriage" and "The Song of Regret," The Shepherdess' lyricism extends to Parajanov-like images of fire burning in the hollow of a tree, a snakeskin held up to the sun, and a bride lifting the edge of her red veil with a hennaed hand. Director Pushpendra Singh and his cinematographer, Ranabir Das, are patient storytellers, and The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs the sort of resulting treasure that New Directors/New Films is at its best when showcasing. (Jeva Lange)

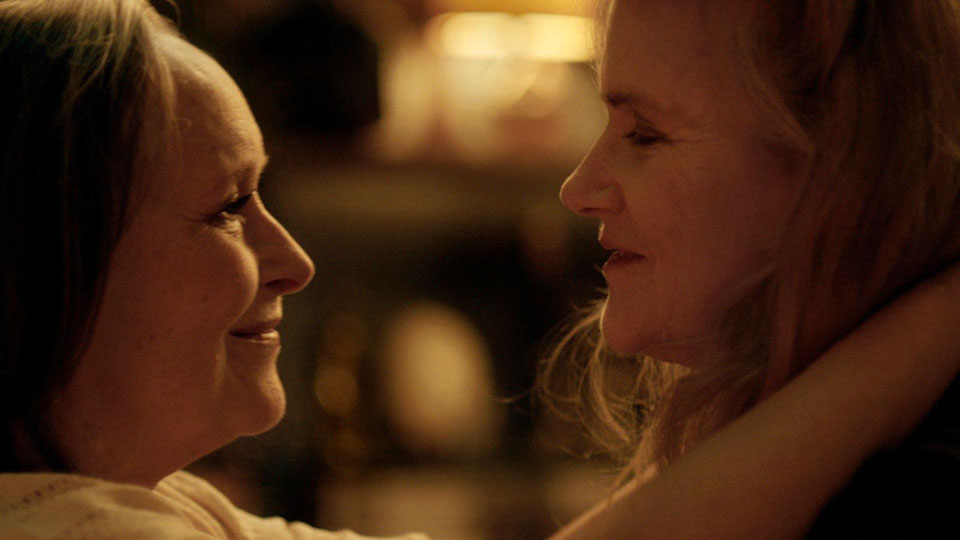

Two of Us (Filippo Meneghetti)

Filippo Meneghetti’s Two of Us is a bittersweet love story chronicling the tortured relationship between two aging women conducting a secret love affair that has been going on for decades. Madeleine (Martine Chevallier) has never been able to summon up the courage to tell her adult children about her and her lover Nina (Barbara Sukowa), even as the two of them make plans to uproot themselves and elope to Italy. After Madeleine suffers a sudden stroke, Nina is stuck having to pretend she’s just Madeleine’s good friend and neighbor (they also live across the hall from each other). Madeleine’s indifferent family members and a paid caretaker cursorily attend to her needs while Nina has to sit idly by, trapped in shame and secrecy.

For all the tragedy of the lovers’ quandary, the saddest character may be Madeleine’s caretaker Muriel (Muriel Bénazéraf), who gets caught in the crossfire of the intrafamilial hostilities through no fault of her own and ends up getting gaslit, fired, and blamed for a car accident she had no part in. The only working-class and non-white character, she gets totally shafted and then—insult to injury—painted as an opportunistic blackmailer. This complicates the narrative, and Nina is suddenly not only a pure victim of heteronormative hypocrisy but also a perpetrator of class violence against her socioeconomic inferior. Apart from Frédéric (Jérôme Varanfrain), Madeleine’s son who blames her for his father’s death and is pretty much an asshole through and through, all the characters are complex, a contradictory melange of bigotry, cowardice, generosity, and tenderness.

Above all, Two of Us is a story of the fragility of the straight nuclear family. Madeleine’s daughter Anne (Léa Drucker) is divorced, and therefore has reason to not be so wedded (no pun intended) to the idea of an inviolable sacred pact between spouses. But she still can’t bear the thought that her mother was not the loyal wife and self-effacing widow she always thought she was. “My mother never tried to start over after his death,” Anne reminisces. “She sacrificed herself for her family.” What a fantasy to entertain even after her own experience of the institution of marriage has turned out to be such a bitter pill. We’re left wondering: if the nuclear family is not as wonderful as all that, why defend it tooth and nail? Is it the only form of intimate social cohesion and emotional and material support still available to us moderns? (Cosmo Bjorkenheim)

Window Boy Would Also Like to Have a Submarine (Alex Piperno)

A trio of globe-spanning narratives woven together through lightly surrealist plot contrivances, Alex Piperno’s Window Boy Would Also Like to Have a Submarine works with the same hypnotic pacing and mystifying storytelling of such art-house somnambulists like Apichatpong Weersakethul or Eduardo Williams. Starting in the Phillipine jungle where a group of farmers chance upon a strange concrete hut that’s appeared out of nowhere, Window Boy is a stylistic and narrative exercise in implanting bizarre structures and connections where they don’t belong.

It’s not long before a single cut unexpectedly yanks us out of the jungle and half-way across the world and into a well-decorated Montevideo apartment where an upper-middle-class woman returns from work. Unbeknownst to her, she is being watched by a young man in janitor’s overalls who has traveled there through a hidden door in her bathroom closet that inexplicably exits onto the worker’s quarters of a luxury cruise touring southern Patagonia. As the man continues to make the trip to the woman’s apartment their shared sense of unfulfilled desire and alienation becomes palpable and bleeds into their disparate environments.

What this may or may not have to do with the Filipino farmers who begin performing exorcisms on the hut is only ever teased at and eluded too. Piperno is less interested in explanations, than summoning phantoms of globalized malaise and inexplicable anxiety. Unfortunately sometimes the film can feel more disconnected than the characters and its absurdities are often more random than illuminating. (Joshua Bogatin)