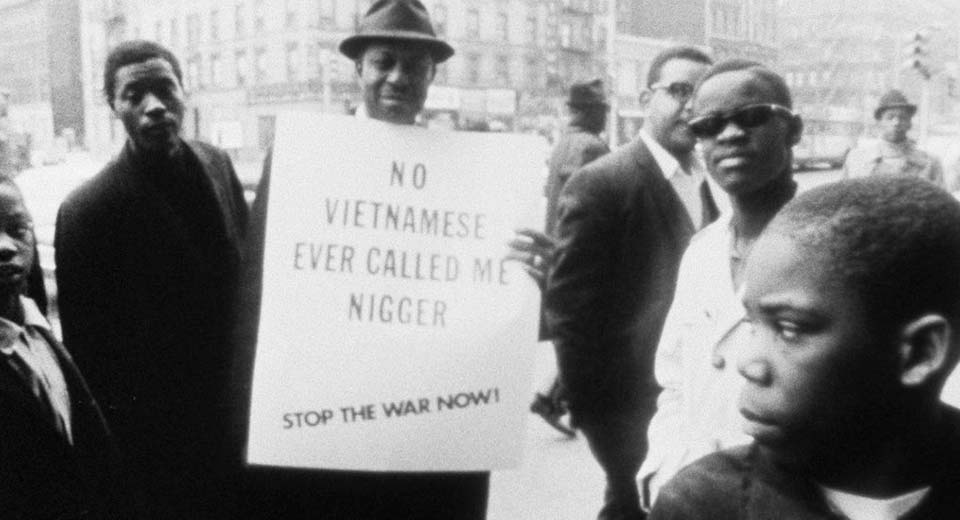

No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger begins with a short scrolling text: “This film was shot in New York City on May 1st, 1968 when three black Vietnam war veterans told us how they felt about the war, poverty, and the black revolution, and on April 15th, 1967 when we filmed the people of Harlem and one section of the largest anti-war demonstration ever held in the United States—the black contingent that marched in Harlem.” It’s an apparently simple statement—what was filmed, where and on what date. But, like the images that follow it, here what looks simple, is actually a complex array of signs; the products of a moment in American culture, when the de-capitalization of Black to black, or placing war in proximity with poverty, were in and of themselves radical political statements.

The first images that we see are the three veterans: an aircraft mechanic, a trained air-traffic controller, and a former RCA radio delivery man. Shot in close-up, we watch as they take turns recalling their tours in Vietnam. Instead of fixing planes, the aircraft mechanic was assigned rat-catching duty. When the air-traffic controller complained about being made a chauffeur, his commanding officer sent him to fight in the jungle. And when the former delivery man heard his C.O. shout “The coons are getting out of hand!” during an artillery barrage, he faced the same realization faced by his fellow black G.I.’s: that a green uniform offered no protection from the pathological racism that circumscribed his life back on American soil.

Intercut with the veteran’s testimonies are on-the-street interviews conducted by a young film crew at the march in Harlem. The contradictory voices that they find there—both black and white—seem to collectively reinforce the veteran’s analysis of late-60’s America as a machine for racial hatred and segregation. But, during these interviews, their images also admit to a fact that has been systematically ignored by all but a handful of American films. The more one listens to the black interviewees, the more one recognizes that, for them, the camera and the microphone are not a neutral presence in their community. Looking into the camera, or at the white woman interviewing them, they address their anger and frustrations to ‘you’. “You and everybody else took everything away from us!” “What we got to be patriotic for? What you gave us? You ain’t give us nothing.” To the filmmakers’ credit, these exchanges aren’t edited out. And the result is one of the more profound images recorded on film in 1967: one of the marchers—a middle-aged black man—looks at the crew’s big, phallic microphone, looks at the young white woman holding it, and proclaims, “the symbol of America, all that America stands for, has this thing pointed at my mouth!”