When I first met Claire Simon, the director of Our Body (2023), during a roundtable for young critics at the Golden Apricot Film Festival in Armenia, she implored us to focus more on documentary; to not just treat them as representations of reality, but to consider the genre as an art form. With a documentarian like Simon, who makes films in the vérité tradition of Frederick Wiseman and others, in which the unadorned presentation of reality is part of the aesthetic paradigm, the impulse to focus on the what of what’s being shown over the how and why can be hard to surmount. Like the woman in Our Body who appears cradling her newborn child and telling the nurse, “Giving birth was just like having tea,” Simon exudes effortlessness in her films. We find ourselves face to face with the marvelous, hardly thinking to question how it was all done.

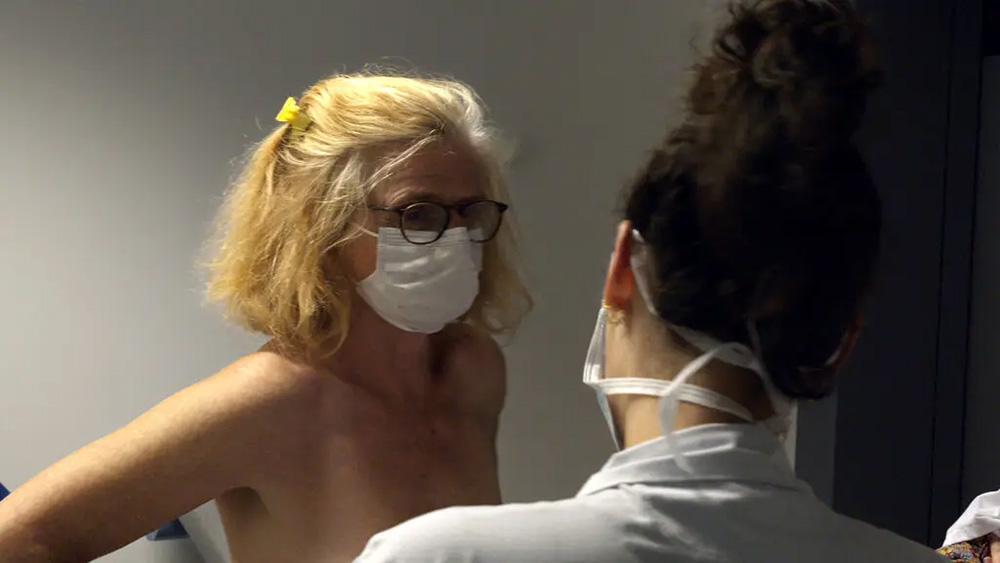

A three-hour low-key epic of the gynecological life of women, Our Body focuses on a single hospital ward in Paris through which is seen the gamut of women’s health. That there is an unfortunate political urgency to the subject matter is undeniable, as is the film’s daring formal and conceptual ingenuity which pushes the project past politics into poetry and philosophy. Simon does not merely depict women’s bodies, but conceives of a collective understanding of the body through cinema and, when she herself eventually becomes a patient, also questions how we might use this understanding practically.

Joshua Bogatin: One of your previous films, God’s Offices [2008], which is a narrative film, was also about a gynecology clinic. What drew you to return to the same subject?

CS: God’s Offices was actually based on documentary material that I shot in different family planning clinics, and the script is just like a documentary. At the time, I thought that since people go anonymously to family planning clinics, it made more sense to do it as fiction. But God’s Offices is not comparable to Our Body. It is more or less the same topic, but Our Body is a real hospital, and the hospital makes the story in the film.

When I met the doctors there, they told me that everything that happens in that clinic is important for the life of women in terms of love, in terms of companionship, in terms of how you see your life all the time. Which is not the reality if you break a leg or if you have lung cancer. It doesn’t impact your life as it does to have a gynecological disease. After two or three days of observing the hospital, I thought, “I don’t want to skip anything. Everything I see is interesting. It makes me mad not to film everything.”

It was at that time I thought about Kierkegaard and the stages of life, which I used to organize the film. Our Body was an occasion to show a complete panel of the gynecological body. It was not only abortion and contraception, but also giving birth, pregnancies, difficulties with getting pregnant, gender transformation, cancer, and all sorts of things. Gynecology is a burden for all women. It can be great, but it also means that, as Simone de Beauvoir said, we have this responsibility for continuing mankind.

JB: God’s Offices was based off of documentary material, but is fiction; why was it important to revisit the same subject in documentary form? How did the fact that everything we are watching is real, change things?

CS: You can’t cheat the body. You can’t cheat surgery. The body is completely involved in the film, so it has to be real because death is real. God’s Offices was really about taking a decision, having a choice. Except for the first consultation in the film about abortion, Our Body isn’t about choice. It’s about coping with your own body. What you can do with it, what it does to you. I don’t see the point of doing it in fiction because it’s always less strong. I think it’s useless to think that fiction is superior. I think the opposite.

JB: That documentary is superior?

CS: Yeah. It’s much more difficult. It’s much more difficult to choose your form because each documentary I make is made completely differently. I am not applying a method or program to subjects or places. I admire a lot of fiction films, but they’re full of stereotypes. I remember that Martin Scorsese used to say that when you write scripts you have to put stereotypes in it, but when you’re a documentary filmmaker you don’t because people carry the stereotypes with themselves. I think it is superior, and I think people think it’s superior because truth is amazing. That’s why [documentarians] are not respected, because people think that we just put our camera down and the truth comes immediately. It never comes easy. It’s a construction, always. As Frederick Wiseman says, he films a three-hour-long meeting and makes five minutes of it. This is fiction.

JB: You move a lot between subjective and objective, often within the same scene and even shot. For example, the opening shot begins handheld, but moves to a static tripod. There are also many moments where the subject unexpectedly turns toward the camera and speaks to you. Why was it important to keep moving between these two different perspectives?

CS: This movement between objective and subjective is really strong in the beginning and the end as well as the part where I appear in the film, but during the rest of the film I hardly talk to people. It’s just this one woman who was waiting very long to give birth, and there was such a long time to wait, so I talked to her. But talking to someone in a documentary is a bit cheap. You don’t want to do that usually because you want to see life truly as it is without your intervention. I think it’s more interesting when you see what is happening and you’re trying to film it as if it was fiction, but it’s true. I don’t feel that my questions are leading the film to a subjective film. In this film it’s very particular because it’s about women, and I’m a woman, so of course the subjectivity comes from there, but the way I talk to this woman who is waiting for her child to arrive is very simple, it’s conversational. I’m not talking to her with an “I.” I always use these very small sorts of interventions in different films just to ease the scene.

JB: It also works with the sense of abstraction and the attempt to reach a collective understanding of the body. By moving back and forth between the subjective and objective through these interventions you’re able to get at something collective.

CS: Yeah, this is the idea. It’s why I never follow the story of any one patient, so that the whole viewpoint of the film is collective. They all speak together, like a chorus. Even though I was very curious with how patients were doing I didn’t want you to follow the story of specific patients because the overall story is youth toward death, through giving birth, not giving birth, changing genders, etcetera. This is the whole story, and it has to be abstract. It’s not an anecdote.

The hospital is a very strange place, it’s a bit like a train station. It’s a place where you’re not in normal life. In the hospital you have the doctors and the patients, but it’s sort of out of this world. It’s very abstract and it leads you to have a point of view on your life and on life in general, that you wouldn’t have in the street or in your home.

JB:You brought up Wiseman earlier. I think the big difference between you and Wiseman is that while he’s always filming place, and people are seen in relation to a place, in your work place is seen more in relation to people and the collective experiences that come out of it. But I’m also interested in how you do film place because you keep coming back to that hallway and that courtyard. Why were those locations important to you?

CS: Because I thought that corridor was absolutely beautiful, with that little garden. I thought that the corridor would be the whole hospital. I always had this very abstract idea of things all the time, and when the women are walking in the film, it’s under that hallway in the basement. I have been filming places a lot and I have been thinking, whether in documentary or fiction, that places can present a new way of telling a story. Instead of looking at the character or the narrative, you can just look at the place. In this film my idea was really abstract. I remember thinking to myself, “I want to do an abstract film, and I don’t want to film the hospital.”

I was relieved when I started looking at the rushes and saw that the patients were so present. If you look at documentaries about hospitals, it’s very rare that the patients really exist. I love Wiseman films like Near Death [1989] and Hospital [1970], but they’re not about the patients; they’re about the institutions. It was not my aim to do a film about a hospital, it was my aim to do a film about this unit and especially the women and what they were going through. Also it’s about our civilization: How do we put names on the body? How do the doctors speak? And how incredible are these scientific inventions? I thought it was important to show the body. I think cinema is very strong in showing things very simply. I think that showing, knowing, and seeing the body makes a very big difference. It gives you a certain knowledge in front of the doctors. Now you know what it’s all about.

JB: But if place wasn’t important, why was it important then to film at only a single hospital? Why not open it up to various different hospitals which treat similar types of patients?

CS: I like the commitment that you make to a single place when you have to go on and on and on to get a film out of it. Otherwise it becomes very journalistic. Suddenly you think, “Oh this hospital has more wealthy people and this one more poor people.” I think you have to choose a single place and go as far as you can with it. I think that you have to become one of the characters of that place. You can change, but if you change a place then it's rotten and it doesn’t work anymore.

JB: You are also literally a character in the film. I think that might not work if you were filming at multiple hospitals.

CS: No, it wouldn’t. And immediately you would have to do comparisons, asking “Oh, how is this one different from that one?” It would give you an attitude as if you had a choice, as if you were above everything. That’s not true when you’re a patient or when you’re a doctor: you’re not above it. When you choose a place, you undertake the risk of that place. When I’m making documentaries I really like to take the maximum risk that I can, otherwise it’s very boring. I hate this idea that you can change everything. For me making a documentary is about embracing surprise all the time; if you don’t discover things there’s no point in it.

JB: There is also something that feels very important and intentional in this film in regards to how you abstract the female body and create this shared language of the body. There’s a sense of political purpose to it. What were your goals and intentions at the beginning of the process?

CS: Two or three days after I began, I thought, ”The only thing I have to do is film the body, to try to see the body. To try to see this moment where they take off their clothes and suddenly they have to appear.” That was really my aim. The bodies I’m filming are not the bodies of women on posters. I wanted to show the other side of the female body, the side that was not made to be shown. The side that was made to be understood, cured, and lived through.

JB: How did people react to your presence, and how difficult was it to establish this sense of proximity and trust?

CS: I am a woman, and we are a crew of women, so it was obvious for every person that we were filming from the point of view of women. There was no idea at all about anything else. The thing is that everyone who says yes gives their experience to others. We’re not guardian angels; we are the persons with whom you could testify your experience for other women. And for men. Because this is all hidden, and everyone knows it. There were a lot of people who didn’t want to be filmed, but for the ones who accepted, it was always because they wanted to share their experience.

JB: Did you keep in touch with any of the subjects after filming?

CS: We haven’t shown the film to the patients yet. I love the African woman who was giving birth and I hope she’s okay because everyone uses her picture. I went back to see her when she was in her room with the child, and she had problems feeding him. Sometimes it happened that I met someone in the hospital whom I had filmed, but not normally. I think when you make a film it’s like love: you do something very strong with someone and then it’s over. The moment of filming is sort of like a trance. When it works everybody knows that we’re doing a piece of cinema together and so it’s a big love. It’s very strong. Then when you stop filming it’s not very interesting.

JB: I also felt a real proximity between you and what you are filming because you always bring your role as a filmmaker into the movie in a very casual manner. When people look at the camera or talk to the camera, it’s very natural. In most films acknowledging the camera would feel artificial and take you out of it, but with you it feels like the opposite, it feels even more sincere.

CS: Yes, it was similar in Human Geography [2013], which was about me and my friend Simone talking to people in the Gare du Nord train station. It was nice because we were not journalists in people’s eyes. Once, my friend Simone said, “We can’t talk to people when they are in a hurry and going to take their train.” I said, “This is exactly a good moment to talk to people because it’s their last words before disappearing.” This is always something that’s important for a documentary filmmaker: you’re capturing the subject’s last words before disappearing. It’s what we harvest. That’s why in Our Body the last woman in the film was so happy I filmed her because it was her last words; at least she has an existence on film.

Our Body opens today, August 4, at Film Forum. A conversation with director Claire Simon will follow tonight’s screening.