Through this weekend, Brooklyn Academy of Music continues its run of Claire Denis’s long-unavailable No Fear, No Die (1990), a tender noir-melodrama hybrid detailing the injustices accorded to two Black immigrants in France, the Antillean Jocelyn (Alex Descas), and Dah (Isaach de Bankolé), from Benin. Bumming around the outskirts of Paris, they find solace (or at least money) in a cockfighting ring underneath a restaurant. Jocelyn obsessively tends to a rooster whose name inspires the film’s, while Dah finds himself entangled with the wife of their employer, played by New Wave fixture Jean-Claude Brialy. Dah realizes they stand to make more money if they put small blades on the claws of the roosters, torpedoing his relationship with Jocelyn.

Queasy-making in its intimacy, Denis’s follow-up to Chocolat (1988) makes perfect sense in the context of her interrogation of colonialism, as the filmmaker has spoken about wanting in No Fear, No Die to accurately depict the subjugated position of the colonized put forth by Frantz Fanon. Yet No Fear, No Die is shot through with pulp poetry (including an epigraph quoting Chester Himes’s My Life of Absurdity) despite its irony-free depiction of the dark odyssey experienced by Dah and Jocelyn. The arithmetic of this world is cruel, but Denis and camera operator Agnès Godard find moments of startling grace following them with handheld 35mm cameras.

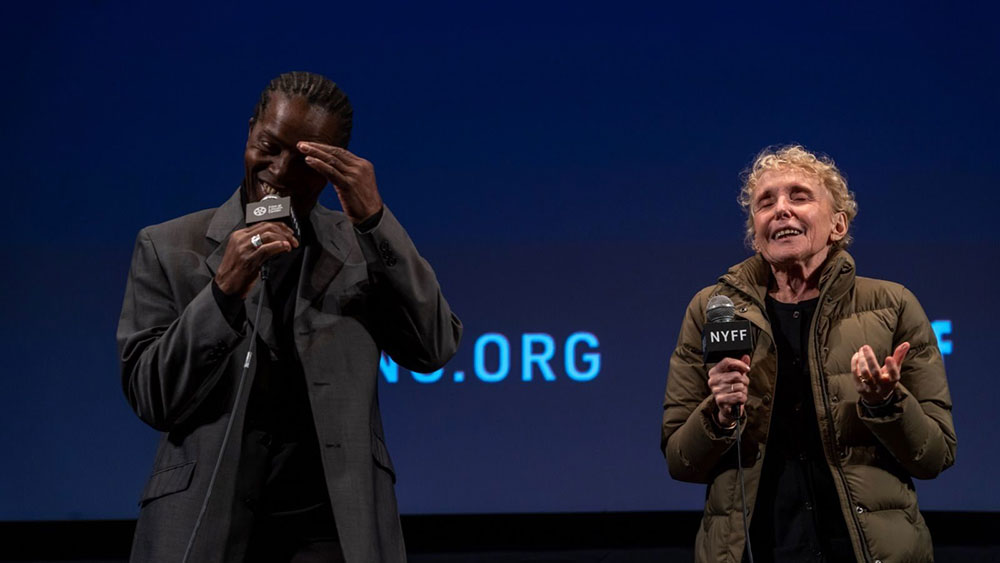

Finally available in a new 4K restoration thanks to The Film Desk, No Fear, No Die should be recognized as major among the year’s repertory offerings (and has proven a hit at BAM.) I was privileged with the chance to conduct an exclusive interview with Isaach de Bankolé and Claire Denis. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Steve Macfarlane: Isaach, can you describe your collaborative relationship with Claire at the time you made No Fear, No Die? Did you have a hand in shaping the character of Dah?

Isaach de Bankolé: I didn’t know Claire before Chocolat. I just got the script and when I read it I thought, this seems weird. Then I met Claire. Sometimes, in Africa, you’ll meet someone named Claire and you’re not sure if they’re a man or a woman. I was taken aback to realize she was white. Reading between the lines of Chocolat, I could tell this person was really embedded into the culture. I felt that this girl,even though she was living in Africa and she was white, was more on the African side than the white side. To write that kind of script meant she was able to get into the minds of people who were on the other side, not her side. She came to me with the idea of No Fear, No Die, and I introduced her to my friend, the playwright Bernard-Marie Koltès. When we were doing Chocolat, I asked the producers if, instead of a partner or companion, I could use my guest ticket to Cameroon for a friend of mine: Bernard-Marie. I knew Claire liked his writing. So he came to Cameroon for ten days or so; this is how they met.

After a certain point she wanted to write White Material [2009], so she and Bernard went to Portugal to write the script, about the trafficking of elephant tusks. Unfortunately, Bernard passed away. Before that, with Bernard, I went to Mexico on vacation. He passed away from AIDS and I knew he was very sick. I wanted to do this last trip because he was more than my brother, you know? I was seeing him almost every day in Paris.

After he passed, Claire came to me and said: “What should we do?” I told Claire I had gotten this idea for a story about two friends. They go on a mission. One never comes back. That became No Fear, No Die. But the idea was supposed to take place in the underground of Berlin, when East and West Germany were still partitioned. Then the Wall came down. I think Wim Wenders was involved in the production at the time. He withdrew and Claire said, “Listen, I don’t know what to do.” It’s funny because Alex [Descas] and I were already in Martinique, training for the cockfighting, when the Wall came down. Claire was a little lost, but she said, “Keep training. I’m gonna see how I can move this film somewhere else.” That’s how the idea started. In the space of two weeks she was able to move the story to the outskirts of Paris.

CD: It was not easy. I was visiting locations in Berlin the Friday that the wall fell. The producer, Philippe Carcassone, told me immediately, “We have to go home. There’s about to be a war here.” I refused. I said, “We are going to live through something great!”

SM: Did you base this world of cockfighting off the real one in Berlin? In Martinique? In Paris?

CD: I saw it with Jean-Pol Fargeau when we were in Martinique. Alex Descas’s brother had some link to the cockfighting circuit in Martinique. The people were betting the most on their own roosters. The fight would last two or three minutes maximum. After the Wall fell, the Berlin Senate decided not to invest money in culture. The Senate told us, through Wim Wenders, that they would not give money to any film. They would save the money for people crossing the border from East into West Berlin, to give them money to live, because it was the end of their world! The producers wanted to pull the plug on the film because they had already lost money on pre-production. But I wanted to move to Les Halles, the biggest open-air food market in the suburbs of Paris. I knew some people working there and we found the places we needed for the film.

IDB: You had previously visited the North of France for cockfighting.

CD: In Romilly, and also in Belgium, there is this tradition of cockfighting—still very strong in the late 1980s. It could not be stopped because it was a historical thing. The state let them go on with cockfighting. It’s very bloody and hard, we’re talking about huge birds with metallic spurs. Then, for some reason, in the food market, I met a Caribbean cop from Guadeloupe who was organizing a cockfight for his friend in a parking lot, in the Paris suburbs. The great luck we had was, as we were in Martinique, we met this man who trained roosters. He trained Isaach, Alex, and me.

IDB: We were waking up at five o’clock in the morning to train with the roosters.

CD: He came from Martinique to Orly with fifty roosters in one plane. He had told me: “If you want to film the fight without killing the roosters, you have never to exceed one minute, or maybe two minutes, maximum, for the fight; anything more than that and they will die of a heart attack.” So for each rooster you see in the film, we had maybe five similar ones, and we had to keep them resting as well as we could.

IDB: The fifty roosters went back to Martinique after.

CD: We are proud to say we killed no birds making the film. I think one of them died of a flu on the plane back home.

SM: Was this an internal guideline? Or did some outside group apply pressure to the production?

CD: Nobody knew we were filming. It was a very small guerilla operation. We found extras in the food market, people from the Philippines, Mexico, the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean—they knew everything about cockfighting. They were betting for real, screaming on-screen like it was a real cockfight even though they were betting with fake money. The guy who found the fifty roosters was on set every day and, at the end of editing, he told us, “Maybe you should put a credit saying no rooster was killed. It’s important for people to know it’s fake blood.” We had a veterinarian with us too.

IDB: These roosters were treated like human actors. The trainer knew their names, their personalities. We fell in love with those roosters when we were training.

CD: He also made them little spurs to protect their claws during the fighting sequence. The prop guy decided to make fake metal spurs in soft plastic, to make sure there were no wounds in the fight sequences. I still have those fake spurs here in my kitchen.

SM: It’s very impressive what you accomplished—the feeling of risk and danger is tactile.

CD: A real cockfight, I have to tell you, is very hard to watch. After the film was made, I was invited, sadly without Isaach and Alex, to attend a famous festival of rooster trainers. I was in Puerto Rico with the film and I saw the cockfight happening in a huge stadium—the roosters coming down from the ceiling in a little wagon-train.

I think I discovered something: in the Caribbean or the Philippines, it’s not secret. In the Antilles you hear roosters at all times of the day and it’s tradition there. The Spaniards held cockfights on the deck of the ship to relax, a kind of sport. Their slaves saw that and decided to hold cockfights on the plantations. It became a kind of symbol of their own fight.

SM: My understanding is that Jocelyn and Dah were written for Alex and Isaach specifically.

CD: Yes. Alex was the dark side of the moon. Isaach had this light, this strength, this optimism. Alex, even at a much younger age, had a shadow about him. He was not a sad person or a bad person. But there was something broken in him. A sadness forever.

IDB: I agree, like he was carrying something from very far in the past for a very long time.

CD: When I went to Guadeloupe, I realized these people are carrying something that does not exist in West Africa. You can be poor, you can be offended by colonial or neo-colonial situations, but you have your own soul, your own land. I think lots of people in the Caribbean have that sadness about them. We had somebody else in mind, a friend I had met through Isaach, a playwright who was young, famous, extremely full of light.

Maybe a month before I started writing with Jean-Pol Fargeau, Bernard died. I was showing Chocolat in New York when Isaach called me and said, “Claire, come home because tomorrow we are going to bury Bernard.” Bernard had told me so many times, “You should adapt one of my plays!” After he died I told Isaach, “We have to prepare another completely different story. And we have to put a goodbye in the film.” This is why we wrote the scene of Dah taking care of Jocelyn’s body, cleaning the blood off of him, putting the money back in his pocket. A complete goodbye ceremony. We did it one shot, one sequence shot. In my opinion, we made it for Bernard. We were crying, not out of pure sadness, but also in saying goodbye.

SM: Were there any disagreements you two had about how Isaach should play the character of Dah?

CD: No. The difficult thing was the first two days of shooting, because the guy doing the lights fucked up the image. Not because he was bad but because he was afraid of not capturing the type of light we wanted. And Alex was shy in a way. “Shy” is not the right word… There’s a kind of fear an actor can have onstage… During pre-production, I had seen an exhibition in Paris of Jean-Michel Basquiat. We knew Basquiat was from Haiti originally. Suddenly, he became one of us. He had already died but Isaach and I copied his clothes.

IDB: He was a great inspiration for No Fear, No Die.

CD: The color of the blood, the color of the roosters, of the people—it was all echoing Basquiat in a way. Also the way Isaach did his hair. It was important to us he wasn't just a painter but also a sculptor, who did statues with blood dripping, like sacrifice, just like cockfighting.

SM: The fashion of Dah changes a little bit in the movie, as he becomes more established.

IDB: The suit jacket, the untucked button-up shirt… Yes.

CD: We looked at many pictures of him. Jean-Michel Basquiat is not a little thing, of course, but in preparing a film you need to hook into little details. You’re pulling little details together.

IDB: You’re gathering all the pieces. “Aha! The white shirt!”

CD: I knew the range of color we wanted on set. Agnès, our DP, would say: “Hey, what’s up with this—white shirt with black skin?”

IDB: It’s hard to read on-camera. But it’s what we wanted.

CD: We said, “Yes, this is what we want.”

IDB: I remember a Basquiat book in the office during pre-production.

SM: Tell me about the life this film had when it was first released.

CD: We finished just in time to be in the 1990 Venice Film Festival. We got a strange prize, like, a non-competitive artistic prize. I was already in Toronto by then. I remember me, with Isaach and Alex, walking in the street the day the film opened in France. We had realized the film was a stranger unto itself in the theater: a film from nowhere. There was no built-in audience for this film. I was proud of it. Abdullah Ibrahim had done this beautiful score. I was happy with everything, and especially the performances of Isaach and Alex. I felt the end was strong. All these people had become dear to me during production.

I don’t remember the reviews; some were good, I guess. But we had no U.S. distribution at all. Venice is not a great place for that. In Toronto, nobody was terribly interested in the film but John Lurie loved it. He decided to distribute it himself, in New York. I think it was at Angelika. At the beginning I thought he offered this as a joke, but he believed in the film and it was really important for him.

IDB: The film was almost like a sci-fi—something really far from the day-to-day reality of most people. [Laughs]

CD: That’s true. But for French people it was, “What is this film about?” I think people have their own lives, and they don’t want to notice the lives of, say, Black people who are living in France, if they don’t have to. More than racism or apartheid, it’s a kind of oblivion, an obliviousness about the world. But all of us knew, in our hearts, that the film had value. We were not desperate! We were happy to have made the film. It was precious to us.

IDB: It’s a film that resonates more with normal people. Normal people. [Laughs] People who did not have a very, very high expectation.

CD: The script was telling that little story and the high expectation was something in the heart, like… We quote Chester Himes at the beginning, there is something…

IDB: There’s also the Bob Marley.

CD: And I did not have the money to buy that music for the film. Bob Marley’s producer came, watched the film in the screening room, and said: ‘“Okay. Take ‘Buffalo Soldier’ for free.”’ So, in a way, we were very lucky that the film was made. We had a producer who believed in it. We believed in ourselves. Together, we knew what we were doing. Sometimes making a film is such a fight if you’re not in the main avenue of cinema. I’m very happy to have made No Fear, No Die.

I was preparing the film with Agnès Godard and I told her, “I think you are only to be the camerawoman. You are not to do the lighting.” For some reason, I felt, if we want to film these two men, who do not belong in this world of the food market, we have to film them with handheld cameras, as if we are walking with them, running with them, driving with them. Therefore, we trained with Agnès in the street, with the camera on her shoulder. I asked a friend of mine to do the light so that Agnès could rest in between takes because it was not a small digital camera, it was a big heavy 35mm camera! And I knew it made us happy as well: we had the feeling Agnès and her camera was always with them, with Dah and Jocelyn. This was the point of the film.

SM: I feel a lot of young people want to make films, but they are not interested in finding details like the ones you describe for inspiration, or for working exclusively with people they love. Some of them want to become professionals.

CD: It exists in every discipline, always. When I go to festivals I meet young people carrying something in them, and they want to deliver. Not all of them are interested in becoming Christopher Nolan.

SM: I’m also speaking as an American. Hollywood has a long shadow…

CD: Hollywood was a school, though. Hollywood is full of little secrets and details. I remember so many Hollywood movies. We learned so much from Hollywood. For me it’s very precious. We learn, of course, from Japan, from Europe, too. But my point is I don’t reject Hollywood. I think some of the most rebellious film directors were working within Hollywood—and these were my heroes.

IDB: Sorry, my Zoom cut out. What were you talking about?

SM: Claire will not be directing Batman.

CD: I watched The Batman [2022] because Robert Pattinson is a friend. Of course, it’s a lot, a lot, a lot of post-production. A crew of 300. But the work inside, the way Robert thinks about Batman—I like the way he constructed his Batman. It’s the rest of it—the effects, the crowds, the post-production, it’s like two films in one. There’s the Batman story, which is very intimate and delicate, and then the rest. I would do a Batman if I could do it without the rest. [Laughs]

SM: Let’s talk more about music: Lil Louis’s “French Kiss” is in the club sequence. Is that something you heard at the discotheque?

CD: It was the same place: the bridge over the highway led to the food market and the discotheque was there. It’s still there—every Saturday night, full of people. When I decided to start filming, I noticed the music. I liked “French Kiss” and it turned out we could afford to license that music [Laughs].

SM: Isaach, I wanted to ask about your own filmmaking. My friend Hisami Kuroiwa loaned me a DVD she produced for the Japanese market, when your film Cassandra Wilson: Traveling Miles [2000] was being released there—a really beautiful, amazing tour documentary…

IDB: Thank you. Yes, it’s hard. Claire is trying to help me but I’m not the production guy, I don’t really know how to raise money. [Laughs]

SM: And it’s harder to find money now than it used to be, right?

IDB: Yes. Even for someone like Claire, or Jim [Jarmusch], it’s a real struggle.

SM: As a filmmaker, is there something specific you can say you’ve developed through your work with Claire? Or, something Claire taught you about directing?

IDB: Not only Claire, but other friends. Jim, for example. You want to feel close to the story they’re telling. Even when I started as an extra in movies, I was interested to learn what happened on-set. The more I knew what was happening, the better a performance I could give. The better I could please my director. So I was interested in lighting, wardrobe—again, details… I don’t consider myself a screenwriter, but if I have an idea, I start to write it down here and there, it becomes a short movie I want to do… So I almost made a short in the ‘90s with Agnès Godard and Claire as producer. And Traveling Miles was the result of that process: we scouted locations in Ivory Coast but we didn’t get the money so I asked Cassandra if I could follow her on tour—Australia, New Zealand. We had put $10,000 of our own money into the production. I went with her and made Traveling Miles. We made that movie just for us. That’s how it goes: when you are not the master of your life’s direction, you adapt.

CD: I have to say, I love cinema and I love to make films, but I am not made for business. In a way, I’m tough, I can resist, but I don’t like to see myself as a “real professional” in the film industry. I’m making the film I like, the film I hope I can make.

IDB: When she says she’s not a “real professional”, if I may say so, I understand. Because in our profession, when it becomes professional, that means you’re gathering experiences and you become kind of a machine. Why I like Claire is, every film is like the last. Or the first!

SM: The last or the first?

IDB: Because we don’t know if we will ever make another movie again. This is a mindset. And for me, that’s where I agree with Claire. Because she can’t be a “film professional” if she’s putting everything into tackling one project at a time.

CD: For me, I need this kind of intimacy with my collaborators. The crew and the actors. I can only do this working with people I love. Casting for me is really interesting, then: I have to make sure I select someone who could be my friend. Otherwise, I won’t make a good film. I’m happy with my drawbacks. Consider the Basquiat images I mentioned: that detail became like our little secret. When I made High Life, it was a science fiction movie. I was supposed to be far away from earth, far away from the solar system; but what was important for me was, this is a movie about a man and a baby. I could probably do a different kind of film, but right now I’m not obliged to. I still manage to do the films I want…

IDB: I’ve made so many films in my life. To me No Fear, No Die is so special because it’s about the soul. And in real life, most people don’t always want to look at their own souls; it’s scary, right?

SM: They, we, will do anything to avoid looking at our own souls.

CD: Like I said, we were still mourning. There is a bit of Bernard in the film. When I say that we need to work with people we love, it also means you pay a lot when they die. Especially when they die young. The pain is big for sure. Good or bad, I don’t know, but No Fear, No Die is pure. I can say that.

SM: It’s pure and it’s a great film.

CD: What makes a film pure? We believed in making the film. It’s not about, “Are we professionals or amateurs?” “Are we Hollywood or not?” “Do we need this or do we need that?” We need to be touched.

IDB: To be real.

No Fear, No Die screens tonight, July 30, and throughout the week, at BAM.

gd2md-html: xyzzy Tue Jul 30 2024