Toward the beginning of Nowhere Near (2023), Miko Revereza presents a digitized spatial model of his family tree, with time mapped as concentric circles. These familial circles are ruptured by migrations from the Philippines to the U.S., which generate new lineages on a parallel plane. Revereza’s Lola (his grandmother) populates the names in the model, having drawn the original sketch of the tree on the back of an envelope in her small Los Angeles apartment.

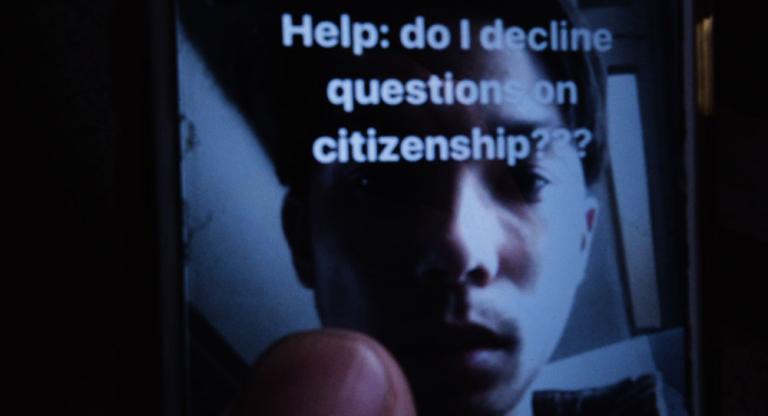

Such exchanges of family histories repeat throughout Nowhere Near, an autobiographical essay film in which Revereza narrates his life as an undocumented Filipino immigrant in the United States, contemplating the unresolved notion of home amid statelessness. Starting in Los Angeles, the film examines his family’s failed green-card applications, the effects of 9/11 on immigration cases, and his bureaucratic struggles as a DACA recipient—also known as a “Dreamer.” In the film’s second half, Revereza—born in Manila and raised in the U.S.—accompanies his Lola to the Philippines, where her recollections compete with reality.

The relationship between Revereza and his Lola testifies to the significance of intergenerational memory in diaspora. As the family matriarch, Lola serves as Revereza’s main link to the Philippines. In Los Angeles, she leads family members through an aerial tour of their town of Binmaley on Google Maps. But upon returning physically to this land, she is disappointed by the changes realized during her lengthy absence. The trees have been replanted, the family’s ornate home has been reduced to just traces of foundation, and her grandfather’s tombstone is no longer positioned at the center of the church. The real estate bequeathed to the family during Spanish colonial rule is no longer theirs. Revereza is a passenger in these scenes, fumbling the camera as he attempts to follow his grandmother on her quest to uncover the home she once knew.

Revereza learns through his Lola but ultimately arrives at different conclusions. Lola’s fond recollections of the American encampment during World War II echo the celebratory nature of Binmaley’s war monuments. Revereza instead points to the violence of this history, linking Spanish colonialism and American occupation with the contemporary reality of policed borders in economies dependent on exploited migrant labor. Perhaps it is these generational dissonances that lead Revereza to conclude with a note on the violence inherent to filmmaking itself. The process of separating and reassembling stories may mimic the disruptions of migration, but memory remains resilient.

Nowhere Near screens today, October 3, and on October 9, at the New York Film Festival, its U.S. premiere.