In the famous six-and-a-half minute tracking shot that ends Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975), the camera begins with the perspective of its main character but slowly moves away from him, passing through the metal bars of a window, circling a nearby plaza, and catching glimpses of village life in a Spanish town as a police car arrives, along with some of the film’s other characters, at the hotel room where the protagonist awaits his death. This shot was the single most mind-altering moment of my early days of obsessive repertory filmgoing. Its impact felt spiritual, not just transcending the film’s story, but shifting my understanding of the world.

In The Village Voice, the film critic Andrew Sarris described this ending—although it is actually the film’s penultimate shot—as the “great conjunction of cinema as narrative and cinema as art object.” His observation only hints at the power of the shot, which fluidly shifts from a subjective to an objective viewpoint, and which simultaneously resolves the story of Jack Nicholson’s David Locke—a dissatisfied reporter who has traded identities with the deceased David Robertson, a man who has secretly been supplying arms to African rebels—while also leaving this story behind to observe the world beyond it. This shot epitomizes the way that cinema allows viewers to slip in and out of identities, and to find new experiences through the act of traveling, by allowing us to be passengers.

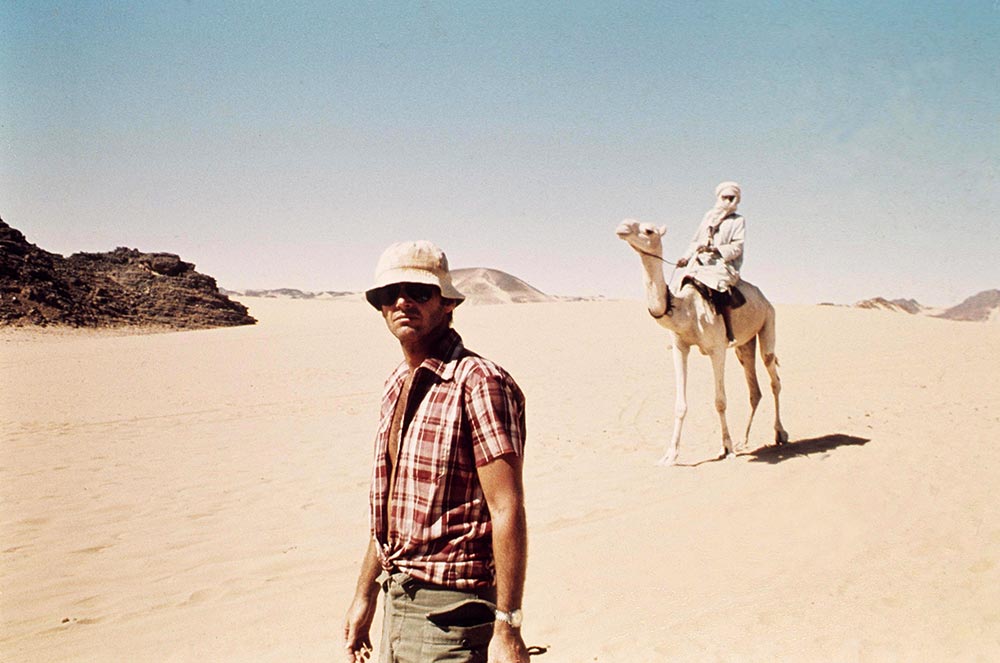

Antonioni himself was a passenger when he made the film, traveling the world to observe the zeitgeist; he made the arthouse hit Blow-Up (1966) in London; the critically lambasted Zabriskie Point (1970) in the American west; and then went to China, where he directed Chung Kuo: China (1972), a nearly four-hour documentary about life during the Cultural Revolution that was immediately banned by Mao’s government. According to Antonioni’s worldview, travel never allowed people to escape the alienation of modern existence. Even though he was fascinated with different forms of revolution, he also found them futile. This is the dilemma Locke, a renowned but disillusioned journalist who goes to Africa hoping to interview guerilla fighters in Chad, faces in The Passenger. And, after failing at his goal, he abruptly abandons his career, his home life, and his past. His wanderings take him through Europe, where he evades Robertson’s pursuers and both meets, and falls for, a woman simply known as “Girl,” who is played by Maria Schneider. In an uncharacteristically snarky assessment for The Village Voice in 2005, J. Hoberman wrote—perhaps channeling Rex Reed—that “having secured Nicholson, showman Antonioni paired the American actor with French hottie du jour Maria Schneider, fresh from Last Tango in Paris and available for sloppy seconds.”

But Schneider is wonderful in the film, which she considered her best. Unlike both Bertolucci and Brando in Last Tango, Antonioni and Nicholson don’t treat her as a sex object. Instead, Schneider comes off as a curious, genuinely free-spirited, and adventurous woman intrigued by Locke’s existential errands. Released between Chinatown (1974) and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), The Passenger also offers Nicholson, in the prime of his career, a precise and understated performance that lends credibility to a fascinating and contradictory character.

Lean and laconic, The Passenger works on many levels; it can be seen as a thriller, a love story, a commentary on modern ennui, or as a sophisticated exploration of the tension between subjectivity and objectivity in journalism (the film’s European title was Profession: Reporter) and filmmaking. In many ways, Nicholson’s Locke is Antonioni’s self-portrait. As Robert Koehler wrote in CinemaScope: “See the film twice and you see two films. See it a third and you see a third. So it goes.” It was the first Antonioni film made from a script he didn’t come up with and it may also be his finest work as a director. Throughout, he seems to be searching for meaning and interpreting the script with each shot.

Even so, this masterwork was unavailable for many years, pulled from distribution by Nicholson after he bought the rights in 1983. It was withheld from theatrical exhibition for more than two decades until Sony Pictures Classics finally re-released it in 2005. Today’s screening, which is taking place as part of Film Comment’s Frantz Fanon series, thoughtfully places it in a context that prompts us to focus on the film’s politics, a dimension of The Passenger that has received little attention. In the film, Locke is a political observer before his identity switch but is drawn to taking on Robertson’s persona, and following in his footsteps by making the appointments noted in the latter’s calendar, because Robertson was a political actor committed to aiding a struggle against authoritarianism. Antonioni leaves it to us to make sense of Locke’s surprising and ill-fated impulse to shift from observer to participant.

The Passenger screens this evening, August 29, at Film at Lincoln Center in 35mm as part of the series “Film Comment Live: The Rebel’s Cinema—Frantz Fanon on Screen.”