Pastoral: To Die in the Country (1974) tells the story of a young Shuji Terayama, more or less, growing up at odds with a rural world mired in the past. Sounds straightforward enough. Apparently Terayama thought so too. But the film folds and re-folds itself in a rush of self-examination until it falls apart, revealing how its apparent contradictions coexist in a multi-layered performance.

Terayama’s film is led by its frustrations with the limits of the coming-of-age genre and its narrative conventions. Time is vexing in the film, which shows a solemn procession of old men dressed like their teenage selves, as well as its teenage main character being forbidden from owning his own watch by his domineering mother. Memory, too; the family next door diligently cleans portraits of ancestors before the world they live in is revealed by the grown-up Terayama to be a total fabrication. And the pastoral genre is another limitation: its strict conventions portray the serene, idyllic countryside as a negative image of the corrupt, encroaching city. The genre shows a natural beauty that is always, at its edges, threatened by the inevitability of death and destruction.

In Japan, Terayama is as well known as a poet, theater artist, and general provocateur, as he is a filmmaker. He led the Tenjo Sajiki avant-garde theater group from 1965 until his death in 1983. Pastoral’s tendency to call attention to its performances enacts Terayama’s desire to “revolutionize real life without resorting to politics.” In his book, The Labyrinth and the Dead Sea: My Theater, he writes: “Imaginary experience and real life are too strongly differentiated; the fine line that separates them is frozen solid. The performance onstage […] is a safe form of imagination that will not invade the audience's everyday reality.” The film frame presents Terayama with a similar challenge, except that unlike some of Tenjo Sajiki’s large-scale performance works, cinema presents the audience with fewer opportunities to become performers themselves.

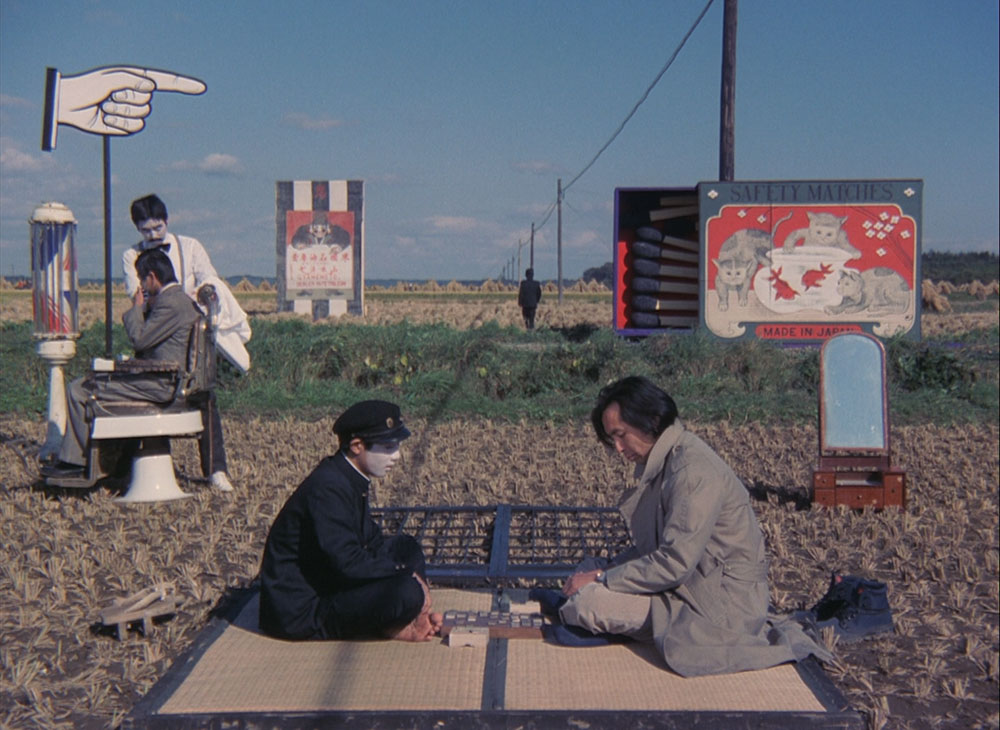

Terayama’s filmmaking centers symbols that seem to take active part in the performance—an array of dolls barreling down a river; a clock that gets more and more broken but keeps ominously, disruptively ticking; the floor that opens up to reveal the place where the dead can speak. The film’s unexpected images ultimately overwhelm its ability to pin them down with language. Pastoral, the director’s first feature film with something like a conventional narrative, feels nonetheless like a successful experiment.

Pastoral: To Die in the Country screens this evening, January 24, at Japan Society on 35mm as part of the series “John and Miyoko Davey Classics.”