In 1971, the French actor, poet, director, and countercultural darling Pierre Clémenti was on a hot streak in his cinematic career; in the years prior, he had worked with high-profile auteurs Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci, Liliana Cavani, and Luis Buñuel (twice) while also prioritizing experimental and short films and theater. But everything changed that July, when he was in Rome after filming Franco Brocani’s Necropolis (1970); Clémenti was arrested for cocaine and LSD possession (which he maintained were planted by Italian police due to his radical leftism), and locked up for 17 months until his release due to insufficient proof.

In the introduction to Small Press’s new edition of A Few Personal Messages, a collection of Clémenti’s writings from those agonizing months, Clémenti’s son Balthazar, present at the arrest, describes his father—like many political prisoners—as “forever haunted by his time in prison,” a fact that is evident in Clémenti’s audacious directorial work thereafter. A series at the Museum of Modern Art through the end of October celebrates the publication—the first time A Few Personal Messages has been available in English—by screening the most personal selections from Clémenti’s filmography, highlighting his pre- and post-imprisonment directorial work alongside a few exceptional performances in the films of others (including Pasolini and Bertolucci, as well as Philippe Garrel and Dušan Makavejev).

The ghostly echo of Clémenti’s prison years can be felt throughout his later work. The series kicks off with In the Shadow of the Blue Rascal (1985), an unnerving, colorful punk noir about police violence and totalitarianism amidst a background of mindless hedonism and a drug war. Shot between 1978 and 1985, Rascal is visceral and unpleasant, visually echoing Clémenti’s desperate words from the end of his time in jail: “The machine destroys men, and if you look at me, you’ll see that I’m the very portrait of destruction. The machine ravages bodies and breaks spirits. And I bring its truth to the most severe consequences.”

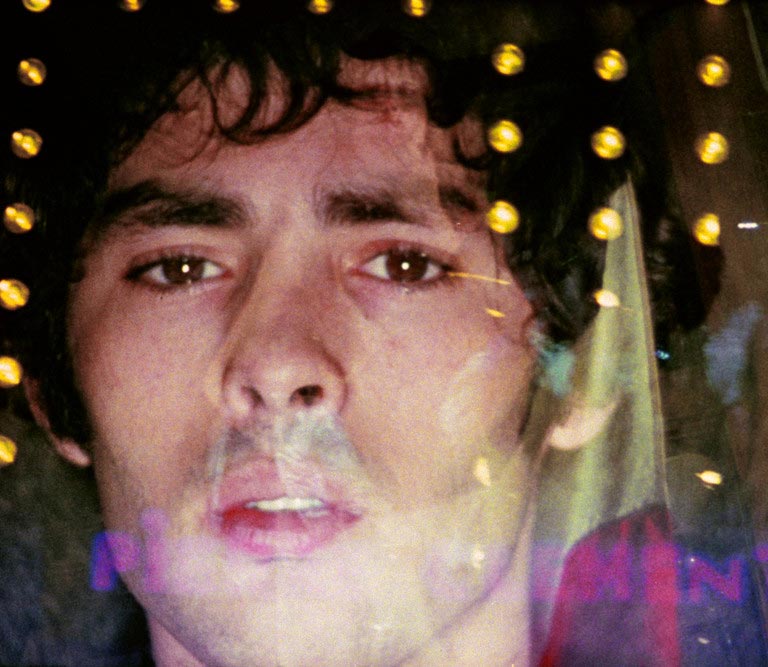

Clémenti’s final film, Soleil (1988), begins with a relatively straightforward reenactment of his arrest and imprisonment. But as the police hold a naked Pierre at gunpoint on screen, it’s clear that the experience has continued to take a mental toll on the man for the 17 intervening years. He is gaunt and balding, nothing like the Clémenti of 1971 who had “a beard, long hair, and the reputation of a hash smoker.” Soleil is an autobiography and a self-eulogy, a montage of footage from throughout his life edited together with overlapping imagery, splashes of bright color, and Clémenti’s own contemplative narration.

An impressive roster of familiar faces dots Clementi’s short, diaristic work: New Old (1979) features footage of Warhol superstar Viva; Tina Aumont stars in La révolution n’est qu’un début. Continuons le combat (1968), Visa de censure n° X (1976), and Positano (1969, screening on October 14 with live score by Lizzi Bougatsos as part of a book release celebration); Philippe Garrel and Nico float in and out of the films. Clémenti’s artistic and personal reputation were so sterling that directors Federico Fellini and Vittorio De Sica, despite never having worked with Clémenti on a film, both testified for the actor at his trial in a show of artistic solidarity. Solidarity with working people, and the belief that the artist must work toward liberation for all, are at the heart of A Few Personal Messages: “Prisoners are on the frontline in the fight against all wielders of power, money, culture. Inside their cells, in the depths of their misery, prisoners bear witness. They are fighting for life.”

“Pierre Clémenti” runs October 13–31 at the Museum of Modern Art.