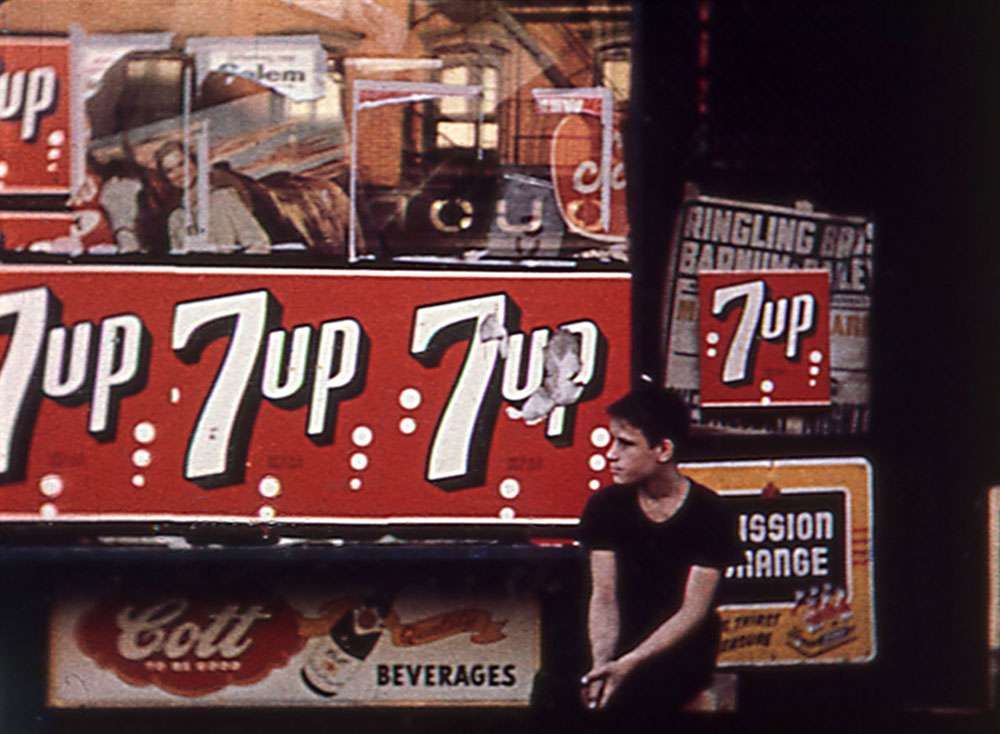

On March 14, 1948, The New York Times photography writer Jacob Deschin covered an art-gallery screening of a short film made by Weegee (Arthur Fellig), who had become famous over the years for his grisly crime-scene images. The tabloid photographer was now an avant-garde filmmaker. Deschin praised Weegee’s New York; “Despite the lack of a story or continuity, both held to be essentials of a well-made movie […] Weegee has managed to produce an impressionistic film of New York so novel that the faults are almost lost in the excitement of the sensational imagery […] Street lights and buildings are weirdly distorted, producing a quality of unreality […] and the movement, atmosphere and tensions of the big city are conveyed through a rapid succession of dreamlike color impressions and familiar action strangely paced.”

Weegee’s New York is made up of two parts: “New York Fantasy” and “Coney Island.” The former is structured as a day in the life of the city and is filled with abstracted imagery. The latter is more of a traditional documentary collage, with candid views of couples kissing, children playing, and people cavorting on the beach and at the amusement park. All city symphony films have some combination of these two modes: lyrical pure cinema and documentary observation. According to the film scholar Scott MacDonald, Weegee’s New York was a favorite at Amos Vogel’s venue Cinema 16 and “an obvious inspiration for a set of New York City symphonies produced during the 1960s, including Francis Thompson’s N.Y., N.Y (1957) and Marie Menken’s Go! Go! Go! (1964).”

The Weegee, Thompson, and Menken films are in Part 1 of “The Postwar City Symphony” program, which also includes D.A. Pennebaker’s first film, Daybreak Express (1953), a study of the soon-to-be demolished Third Avenue El. Through a miraculous fusion of music (a Duke Ellington recording from the early 1930s), camerawork, and editing, Daybreak Express perfectly converts the rhythms of jazz into cinema. Thompson was an accomplished director of industrial films who went on to direct the first IMAX film, To Fly, in 1976. His short masterpiece, N.Y. N.Y, was made over the course of eight years and uses an array of prismatic and kaleidoscopic lenses to create a Cubist ballet—a vision of midtown Manhattan where gleaming skyscrapers, cars, and buses all appear to take flight and the metropolis comes to life as a massive and vividly colored organism made of steel and glass. Another tour de force in Part 1 is Marie Menken’s pixelated stop-motion joyride Go! Go! Go!, which zips through Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Staten Island in its frenetic eleven minutes, barely pausing as it takes in, among many other things, a college graduation (Wagner College, where the poet-filmmaker Willard Maas taught), a body-building contest, her trip to Coney Island, and an outdoor dance performance.

The four films in Part Two are almost never screened. They are all fascinating and one is a revelation. Michael Jacobson’s The Burning of New York (1967) takes a Brakhageian stroll across the 59th Street Bridge—the filmmaker uses bleached and tinted film stock to abstract the imagery. Rick Liss’s No York City (1983) picks up where Go! Go! Go! left off, starting with a speeded-up boat ride toward the downtown skyline—the World Trade Center is a haunting presence in the 1980s films—and hurtling chaotically around the city, hilariously pausing for a few seconds for a Central Park boat ride with a trio of mimes. The energetic electronic soundtrack collages Laurie Anderson’s “For Electronic Dogs” with street noise. Peter Von Ziegesar’s Concern for the City (1982) offers a contemplative and defamiliarizing view of the urban environment, with a moody electronic score enhancing the haunting mood of its distant views of the New York landscape while always foregrounding nature. In one of its closing shots, the World Trade Center appears as a miniscule presence from the marshes of Jamaica Bay. The gem I alluded to earlier is Steven Siegel’s Dream City (1987), which invigorates the city symphony by incorporating interviews with young people who comment on such things as the pressures of income equality and the joys of graffiti. The film captures both the decay and vitality of pre-gentrification, pre-Giuliani New York, and the energy of hip-hop culture in ascendancy. This is the rare city symphony film where the actual voices of the city’s residents take primacy over image and music.

While all of the films in the City Symphonies programs were made as personal artworks, it is worth mentioning that one of the series’ remarkable finds is a city-sponsored documentary, What is the City but the People? (1969), which plays tomorrow. This 51-minute sponsored film was produced by the Department of City Planning to build public support for its comprehensive vision to revitalize neighborhoods throughout the city and fight the flight to the suburbs spurred by the turmoil and race riots of the late 1960s. An incredibly well-made documentary—it was photographed largely by Arthur Ornitz, who went on to shoot Serpico (1973), Next Stop Greenwich Village (1976), and An Unmarried Woman (1978)—the film is filled with interviews with local residents and is candid in its depictions of the city’s myriad problems. Yet it paints an even bleaker view of life in the suburbs, arguing for the need to improve the quality of urban life. What is the City but the People? is an invaluable document that captures the unique flavors of many New York neighborhoods, starting with Hell’s Kitchen. Even though it was created as propaganda, it is a time-capsule that shows a more panoramic and authentic view of city life than nearly any other film from the time. Whatever form they take, all of these films can’t help but reflect the city’s imperfect, chaotic, and always kinetic energy.

The Postwar City Symphony is a two-part program that screens tonight (Part One) and tomorrow (Part Two), with repeat screenings of both parts on May 7 at Film at Lincoln Center as part of the series “Seeing the City: Avant-Garde Visions of New York from the Film-maker’s Cooperative Collection and Beyond.” Film professor Erica Stein will introduce the May 3 and 4 screenings.