Henry Fonda starred in some of the best American films made from the 1930s through the 1980s, and one in Italy, Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West, from 1968. Fonda was of course also the father of Jane Fonda and Peter Fonda, significant Hollywood actors and activists in their own right, who are often portrayed as clashing with their emotionally distant father. The Austrian writer, curator, and film historian Alexander Horwath’s new documentary, Henry Fonda for President – the name comes from an episode of the 1970s sitcom Maude – dispels certain myths about Fonda, and about America in the process.

Horwath’s film is at least three things: a study of Fonda’s career, a social history of his films as they relate to developments in American history from the 18th century to the present, and a clear-eyed, coast-to-coast travelogue by a European, in the tradition of Alexis de Tocqueville and Jean Baudrillard. It succeeds in all three, its three-hour running time breezing by in rich detail that combines scenes from real landscapes and towns in which Fonda’s films took place, with excursions into Omaha, where he grew up.

Forever associated with the character of Tom Joad, from John Ford’s 1940 screen version of John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath, Fonda had a haunted, existential quality he also brought to other Ford movies (Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, Fort Apache, My Darling Clementine). The way he says the word “homicide” to a suspicious truck driver in The Grapes of Wrath is perhaps the essential single-word moment of acting in American cinema.

All-American but depthful and conflicted, Fonda was attracted to characters who were wrongly accused, making him an ideal actor for noirish stories of innocent men on the run or caught in the gears of an indifferent justice system, such as Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once (1937) and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956), twin masterpieces that bracket the first two phases of his career and encapsulate the hardest aspects of the 1930s and the 1950s in America. Henry Fonda for President argues that Fonda was an acteur who created his films along with their directors to describe a social reality in which—to paraphrase François Truffaut on You Only Live Once—we are told everything is going well when in fact everything is going bad.

Horwath, before this recent turn to filmmaking, was for 30 years the director of the Viennale film festival and the Austrian Film Museum. We spoke by Zoom and followed up by email. Our conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

A. S. Hamrah: You say in Henry Fonda for President that Fonda was not conscious of his image. And near that point in the film, there's also an interesting quote about him: “He has his eyes on losses and defeats.” If Fonda was not conscious of his own image, how would you sum up what his image was?

Alexander Horwath: He was conscious of his image the way it was reported in the press during his lifetime. He says that to Lawrence Grobel in the interview at the beginning of the film, the interview Grobel recorded over several days in Bel Air at Fonda’s home in the summer of 1981, near the end of Fonda’s life. Fonda says that he reads that he’s supposed to be a symbol of integrity, to represent the Good American. “I read it,” he says, “but it doesn't mean anything to me.” He feels distanced or detached from what the general view of his iconic status was, from what his persona was.

He was more skeptical about himself than that. And he did not like himself. I believe him when he says it. He was more critical about himself than I think big movie actors generally are, critical about what his actual achievement was. I think he viewed himself as a kind of zero, or as a puppet in the hands of authors, writers and directors. The only thing that he thought he was very good at was acting. He knew he was a good actor, and he was very serious about improving his craft. But he thought that all the things that people read into him were not necessarily true of him as a person.

I think he was an author, too, not as a writing author, but the way he performed his parts creates a kind of script or text. For instance, the example you gave that he has his eyes on losses and defeats, that comes through to me in the way he acts in certain parts, yes, but also in his tendency to place himself in similar situations throughout his career in which this inward-looking capacity comes out.

ASH: Interwoven throughout Henry Fonda for President are excerpts from this interview you mention that Fonda did when he was 76, a year before his death. His voice sounds different at that stage in his life than it does when he was making films in his prime. I was wondering what this Grobel interview was, exactly, and how you came across it?

AH: I knew the interview existed because it was quoted in various places. It was for Playboy magazine, and it was one of two things that Fonda’s family convinced him to do as his life was coming to an end. Jane Fonda realized he hadn’t long to live, and she wanted him to leave some sort of legacy behind. He had not wanted that before, so his family talked him into two things. One was to write an autobiography. He said, I'm not going to write an autobiography, no way. But this guy, Howard Teichmann, a playwright, had written some books he liked, and he agreed to spend a couple of months with him, telling him about his life. The book that came out of that in 1981 is called Fonda: My Life, as told to Howard Teichmann. That's his quasi-autobiography.

In order to promote both that book and On Golden Pond, his last film, which also stars Jane as his estranged daughter, and which had a release date of December 1981, his family also convinced him that he should do the Playboy interview. At the time, the Playboy interviews were a big deal, you know, serious journalism, and he agreed to it. And Lawrence Grobel was the writer who did it. He came for a week, every day for two hours, because Fonda’s wife said not longer than two hours, Hank is still weak. He had just come back from the hospital. He had heart problems. Grobel visited Fonda at home six days in a row, and the twelve-and-a-half hours that resulted still exist on tape.

I found Lawrence Grobel, contacted him, and he agreed to—I mean, we paid for this, of course, but he had the tapes and we digitized them, and then I spent months transcribing them. And getting into it was almost, how should I say, like getting into Fonda’s skin. The sound of this now creaky and fragile voice, and the sounds of the birds in the background, really put me there with him.

This was quite a fascinating period in the work, and I realized it would become the second line of narration in the film. I knew my voice would play a certain role, but it was a great advantage to have Fonda’s. I was very happy when I realized that there could be this second track and that my own thoughts and words would be there, and Fonda’s very different way of relating to himself and his roles would be there, too, so they could dialogue, a sort of intertwining of those two lines. That made the film. We started this in the spring of 2019 when we had our first research trip in the US, and it was only in 2020 that I knew I could use the interview.

ASH: You mention your first trip to the US. Henry Fonda for President is made up of clips of films that Fonda stars in, and various non-film sources—television, advertising, various other things. But a lot of the film is made up of footage that you shot yourself. The way you present the American landscape was so effective in the film, detached but with a certain drive.

AH: This is my first film. I've not made films before. I was happy to be able to do this with my partner, Regina Schlagnitweit, and with Michael Palm, who is an old friend and a great editor. He makes his own films, but he’s also a cinematographer, and he was the one with the real technical expertise.

ASH: So he shot the film on location when you went on those trips? I guess one of the trips was during the height of the pandemic?

AH: It was the three of us on both trips that we made for this project, sometimes sleeping in the same motel room. The second trip, for the main shooting period, we had to get special permission from the US Consul in Vienna. Once we were there, it was easy, because in the places we visited in the Midwest there were not a lot of Covid measures. However, certain locations were not so easy. Offutt Air Force Base outside of Omaha was not so easy, but we met a lovely guy who helped us.

ASH: The man in the orange fleece jacket that we see in the film?

AH: Yes, we asked him if he would be the person to guide us, to lead us down there into the bowels of the Cold War. It actually did last six minutes to walk down there, floor by floor by floor, as I say in the film. We were happy to not be a big crew, just three people who could speak to whomever we wanted. We just asked if it would be okay to film at the Wheat Patch Camp, as it was called in The Grapes of Wrath, for instance, the Weedpatch Camp in Arvin, California. And the lady, Sharon Garrison, who takes care of the historical buildings there, she and her daughter were so friendly in allowing us to shoot.

ASH: They do seem friendly. One aspect of most of the places you shot is that they're deserted. The Offutt Air Force Base and the Craig House, which was the sanitarium in Beacon, New York, where Frances Seymour Fonda, Henry’s wife and Jane and Peter’s mother, took her life in 1950.

There's this sense in Henry Fonda for President of this kind of past glory that is in ruins. The Craig House is an abandoned mental institution and the Offutt Air Force Base is especially sad-looking. Presumably America’s nuclear arsenal is still ready to go at any minute, somewhere, but it sure isn’t there. When you started the film, did you expect these to be such haunted places?

AH: We expected it and we like those kinds of places. Regina and I have been to the States many, many times before. We are always drawn to the non-glamorous. Our friends in New York and Los Angeles ask us why we spend so much time in areas of the United States that they would never have any interest in visiting. But I think the hauntedness of Henry Fonda himself is part of this. He was a haunted character. I should mention a wonderful book about Fonda by Devin McKinney. It's called The Man Who Saw a Ghost. It's the best Henry Fonda biography, by far, and was helpful in focusing some of my thoughts. The Craig House we knew was no longer a functional place and it would be closed, but that was simply a case of driving there very early in the morning, six or so. The grounds were not locked. We just went in there and we filmed for a few hours until a car came speeding in and a man threw us out.

ASH: One place that you really use quite well is also a place that your friends in New York and Los Angeles probably don’t like to go: Times Square. You combine the theater where Henry Fonda made his Broadway debut as a lead actor, which is where Hamilton is now performed, with the big sign for David Byrne’s American Utopia, and then this gigantic video billboard with Brad Pitt, and in front of it is a man dressed as Donald Trump, in a Trump mask, posing with tourists and mock-directing traffic. Most people think of Times Square as a kind of void, yet this all ties into the themes of the film so succinctly.

AH: Fonda talks a lot about his early days in New York, trying to make it as an actor on Broadway and not getting a lot of parts for several years, living on salt and rice, as he says. It made me think of the many small-time performers, dancers, costumed folks I had often observed on Times Square at night. All those nobodies in the shadow of the big stars, and the vague desire to be seen or discovered. For me that had to be the location, or the ghost scene, for the “New York, early 1930s” chapter of the film. And the fact that the 46th Street Theatre—now called the Richard Rodgers Theatre—where Fonda did break through in 1934 is just around the corner was perfect too. We would have filmed at that stage door anyway, but we got even luckier with Hamilton on the program there now, and the “History is Happening in Manhattan” sign above the front entrance. Michael’s camera just sucked up everything we encountered there for six hours, and in the editing we managed to condense several of our themes with these images.

ASH: It’s interesting that you include the audio clip of Fonda saying he could never do Shakespeare on the stage because his voice is too American. You illustrate this with the Hamlet scene from My Darling Clementine, in which Victor Mature, as Doc Holliday, finishes the drunken actor’s soliloquy as Fonda’s Wyatt Earp looks on. Mature was not considered a great actor, but here, under John Ford’s direction and playing against Fonda, he becomes great. Why do you think it works so well?

AH: I think it has to do with contrasts. The fictional 19th century ham actor who forgets his lines vs. Mature, the 20th century movie ham who, via Hamlet, discloses an inner life that we don’t expect of him—or of the Doc Holliday character that he plays. And then there is the silent Fonda, just observing this new friend, or opponent, Doc Holliday—and maybe at the same time discovering something about his Hollywood colleague Victor Mature. In the back and forth between them, Ford devotes almost as much space to Fonda’s observational acting as he does to Mature’s Hamlet monologue. It allowed me to touch on more than one thing at the same time.

ASH: I don’t believe that seeing films, even documentaries, is primarily about learning facts, though that is an undeniable part of the cinema. But I did not know about the village of Fonda in upstate New York, or about the Henry Fonda Memorial Highway or the Henry Fonda Rose Garden in Nebraska. I was glad to find out about those places. I was also surprised to learn that after Margaret Fuller died at sea in 1850, Karl Marx took over her job as a foreign correspondent for the New York Tribune. How did Fuller become a character in Henry Fonda for President?

AH: My own interest in the cinema probably also came from its role as a sort of counter-school. But that still makes it a place where you can learn things—getting new information, and getting it in a different way. Films have often educated me about the world. And they helped me become aware of the fact that all knowledge is contained in and expressed by a specific discourse or costume. It never appears naked. So I think I did want to impart certain kinds of information with this film, but in a way that also does justice to the medium.

Margaret Fuller came in sideways. Once I had decided on going to New Salem, Illinois, to actually look at the young Abraham Lincoln’s cultural milieu, I needed to know more about the 1830s. I re-read Tocqueville, I looked into Andrew Jackson’s policies, and I discovered Margaret Fuller who is practically unknown in Europe but a major figure in the Transcendentalist counterculture of her time. I got Megan Marshall’s biography of her, A New American Life, and I read many of her essays, and I was amazed by her reflections on how the original promise of the United States had been squandered just fifty years after the founding of the county. Her social criticism was as striking as her feminism, and I immediately included her among my fifteen or so satellite figures.

To me, these historical characters represent certain shades of Henry Fonda and of the US. After creating a composite Fonda out of his actual life and his screen lives, I also wanted to split him up again into these other layers and lives and moments of American history. With some of these figures, there is a factual connection, like Wyatt Earp, William Brown, or Adlai Stevenson, and with others it is more of an association on my part, like Margaret Fuller or Saint Kateri Tekakwitha.

ASH: Fonda’s choices as an actor in movies weren’t always his own. But he does seem to have been drawn to characters from the underclass—the unemployed, the falsely accused, the downtrodden, victims of the Depression. We learn in your film that Fonda, when he was 14, witnessed from his father’s office the infamous lynching of Will Brown, a Black man falsely accused of raping a white woman in Omaha in 1919, and that it left him with a profound sense of outrage that he carried through his life. Do you think that experience led him to films that included lynchings? Young Mr. Lincoln, The Ox-Bow Incident, The Male Animal, and Once Upon a Time in the West all deal, in one way or another, with innocent men being lynched or executed.

AH: I do. It's an event he often talked about in interviews. How it shocked him and that it was an important part of how his worldview was formed. But as becomes clear in my film, he would never publicly accept the notion that through his work as an actor he was able to transform such experiences and convictions into a kind of personal authorship. Part of it is the choice of roles, whenever he did have a hand in it, an inclination towards certain subjects. But what’s equally important is the way he acts, the delivery, as Isaac Stern tells him in our excerpt from The Dick Cavett Show.

ASH: The quote you include from James Baldwin is revelatory. How was it that Fonda could be seen as not-white when he is also the consummate WASP?

AH: That’s hard to say. But when I read this in Baldwin’s book about watching movies, The Devil Finds Work—recalling his conversation with a Black friend who thought that Fonda’s walk at the end of The Grapes of Wrath is not a white man’s walk—it chimed with my feelings about Fonda. There is a long passage Baldwin writes about You Only Live Once, where he already goes into his ideas about Fonda and Sylvia Sidney. That was an important film to him, and through that he comes to the part about his friend saying that about Fonda in The Grapes of Wrath.

These are all projections, of course, but like Baldwin’s friend in the 1940s I think there is more to Fonda than his Midwestern identity, the American Gothic type that friends and family often saw in him. He contains, as they say, multitudes, and I felt that some of these layers or souls that walk with him could be made visible.

ASH: Did Baldwin know Fonda had witnessed the lynching of Will Brown in 1919?

AH: I don't think so, no. Fonda’s family background, you would not call it proletarian, as you would for instance with John Garfield or James Cagney. Fonda was middle-class. He says his family was one of the few liberal families in a hotbed of reactionary worldviews in Omaha. He was, as opposed maybe to peers of his like Cagney, able to also play the egghead, the intellectual, or a patrician politician.

ASH: Yes, and do the awkward comic turn in movies like The Lady Eve [1941]. He never projects the cockiness of Cagney or Garfield.

AH: Or the very expressive, street-smart kind of person, a New York person.

ASH: Or a psychotic criminal, either, like Cagney in White Heat [1949]. Even as the villain in Once Upon a Time in the West, his way of inhabiting evil is secret and inward. Which reminds me that you connect him to Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver through a TV commercial Fonda and Jodie Foster did for View-Master five years before Taxi Driver [1976], when she was an unknown child actor. Then you connect him to John Hinckley, the man who shot Reagan to get Foster’s attention.

AH: And through the fact that De Niro received an Oscar for Raging Bull [1980] on the very same night in 1981 that Fonda got his honorary Oscar, which was postponed for a day because of the Reagan assassination attempt.

AHS: Yes, it was broadcast 24 hours after Hinckley shot Reagan.

AH: Reagan introduced the Academy Awards ceremony in a pre-recorded segment, talking about what movies mean. And then De Niro got Best Actor for Raging Bull, and Fonda gets the Lifetime Achievement Award.

ASH: You mentioned how Paul Schrader got the idea for the character De Niro plays in Taxi Driver because of Arthur Bremer, the man who shot the segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace while he was running for president in 1972. I don't know if you’re aware of it, but Arthur Bremer wrote film criticism in his journals.

AH: He wrote about films?

ASH: Yeah, he writes about movies that he saw. I only know one entry. It was about Otto Preminger and Elaine May’s Such Good Friends [1971]—of course we learn in your film that Preminger directed Fonda in the post-war noir Daisy Kenyon [1947]. Bremer writes that Such Good Friends was terrible, he says it was as bad as Russ Meyer’s Vixen [1968]. And then he went and shot George Wallace. So there’s a film criticism angle to American political assassination attempts.

AH: Everyone’s a critic.

ASH: In the film you call television a doomsday machine, comparing it to nuclear weapons. Yet at the same time Henry Fonda for President reclaims certain Fonda-starring films for the cinema, films that were at one time seen as permeated with TV values and somehow uncinematic. I mean 12 Angry Men [1957], Fail Safe [1964], and The Best Man [1964], in which Fonda plays somewhat elevated, ethical men who face life-and-death choices. Put into conversation with Ford, Lang, and Wellman films from the 1930s and ‘40s these movies now almost seem comparable works in which a certain kind of black-and-white cinematography, elucidates moral issues. Was that something you were conscious of?

AH: Semi-conscious maybe? I always knew that in older cinephile circles these films carried a certain stigma, but in my own discovery of American film history they had been as important as those from the classical period, not just thematically but also in their aesthetics. Thirty years ago, I did a big show entitled Cool for the Viennale and the Austrian Film Museum. It dealt with 1960s Hollywood cinema and US politics. And already at that time I defended certain non-classical qualities in films by Lumet and Frankenheimer. That show already included Fail Safe and The Best Man, next to fifty other works. The fact that cinema lets itself be influenced by other media, old or new, was never a problem for me. Quite the opposite. I like the essential impurity of cinema.

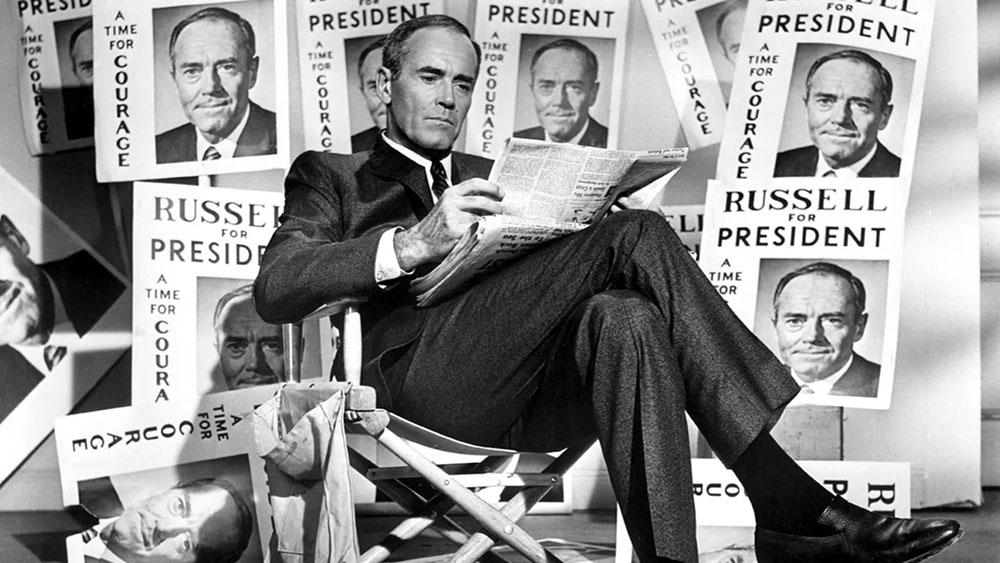

ASH: After Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man, Fonda becomes in his films a presidential figure. You see him as an alternative, fictional, better version of Adlai Stevenson, and as a counter to Nixon and Reagan. This becomes literalized by the 1970s, in the Maude episode Fonda guest-stars on as himself, in which Maude tries to get him to run for president. Did you already know about this sitcom episode before you started the film, or was it something you discovered in the process?

AH: This, too, came from my earlier work as a curator. In 2017, I ended my long stint as director of the Austrian Film Museum with a number of very different programs, one of them centering on Fonda. And I came across the Maude episode during my research for that program. Maude had never been broadcast in Austria or Germany, it was completely new to me, even though I was familiar with Norman Lear and the fact that he and Fonda were friends. When, in 2018, I was seduced into trying my hand at filmmaking, that episode definitely played a role in convincing me that the subject and approach I had suggested to the producers had some substance.

ASH: It’s amazing that the same bridge linking Arizona and California appears in both The Grapes of Wrath and Easy Rider, the Old Trails Bridge on Interstate 40. Henry Fonda, as Tom Joad, crosses it in a jalopy The Grapes of Wrath and then about thirty years later his son, Peter, re-crosses it on a motorcycle in the other direction as “Captain America” in Easy Rider. Were you aware of this before you began the film, or was it a discovery?

AH: I’m not sure anymore. I think Peter mentions this in his autobiography, Don’t Tell Dad. He sometimes spoke about imagining himself as a Tom Joad for his own generation. I had re-watched Easy Rider before we visited that location during our first shoot and research trip, in 2019, and it was obvious that it would become a central spot for the film. That day, we also spoke at length to a strange guy who lives there in a trailer, in full view of the bridge. A Californian ex-surfer who had lost his business in Los Angeles to “some Asians who tricked me”, as he phrased it, and had chosen to move to the Colorado River on the Arizona side of the border. There was more than one character in this guy, too, a racist, an old hippie, a bundle of disappointments.

ASH: Fonda, like George W. Bush, took up painting later in life. In the film, you show a large, detailed black-and-white drawing he did of a magnifying glass over a passage from the novel The Grapes of Wrath. I found the way Fonda chose to emphasize this passage from John Steinbeck’s book quite moving, especially as it came near the end of his life. He wanted no gravestone, and in a way he wanted to be forgotten, but this drawing seems to indicate an awareness of his legacy. Why do you think he drew it?

AH: I think it was his way of indicating things that he wouldn’t say out loud. Among his many paintings and drawings, at least among those I saw, it’s the one that’s closest to a statement, maybe even relating to the mid-1970s present in which he drew it. He draws two pages of the open novel, and the magnifying glass puts one paragraph in sharp focus. It begins like this: “And the companies, the banks worked at their own doom.” The last sentence is: “And the anger began to ferment.”

ASH: The color scene you include from the movie Spencer’s Mountain [1963], in which Fonda decides to burn down the frame of a house he has been building, wraps the film up so starkly and with a great deal of melancholy. This late role of his underlines how he wanted no special recognition, and also underscores your film’s view of the 1960s and the America of today. How does it tie into your view that Fonda’s role in the cinema was to somehow portray “the president of the nameless”?

AH: In the film Spencer’s Mountain, the scene of the burning means that he relinquishes his dream home on the mountain to pay for the college education of his son. But as you say, it taps into some larger themes that I was trying to follow at the end of the film, also including moments from The Wrong Man and My Name is Nobody. Fonda himself wanted to “turn into dust,” but he had also partly dedicated his craft to the “nameless ones,” highlighting his conviction “that there is no such thing as an unimportant person,” as Robert Redford phrased it when he handed Fonda his Oscar in 1981. I connected that scene to an audio passage from the German philosopher Günther Anders. It comes from a short story of his. In the English translation it goes like this: “So then, in the most profound grief, disguised in the costume of truth, the actor of a pain that was his real pain, a survivor of tomorrow’s dead, he stood in the noonday glow of his deserted street.”

Henry Fonda for President screens this evening, April 3, and throughout the rest of the week at Anthology Film Archives. Alexander Horwath will be in conversation with Kent Jones following Friday and Saturday’s screenings.