Few directors have navigated both knee-jerk revulsion and repentant revaluation so deftly as Mary Harron. Though now considered staples of American independent cinema, the writer-director’s films have hardly been met with immediate acclaim. Even American Psycho (2000), unquestionably her most beloved film, took its sweet time rising to a point of cultish veneration.

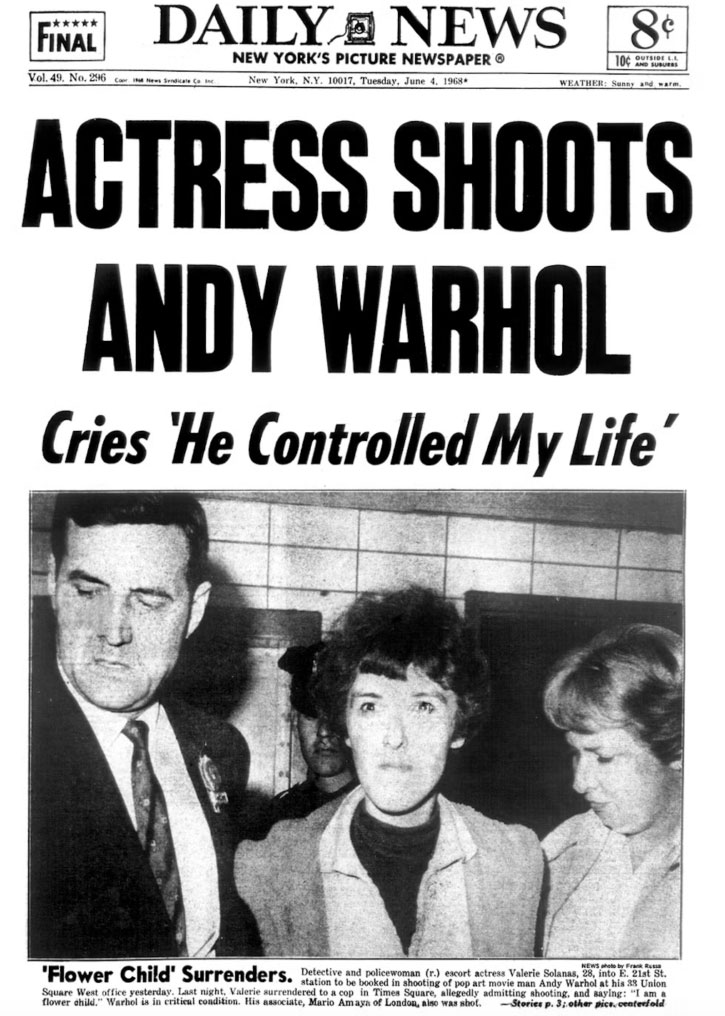

Who better suited, then, to reassess one of American culture’s most reviled visionaries? Harron was working in non-fiction TV when she first became aware of Valerie Solanas, the raffish proto-radfem best known for attempting to assassinate Andy Warhol in 1968. Stumbling upon a copy of Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto a couple of decades later, Harron was taken with the anachronistic brilliance of her political thought and galled by how much of it had been written off as lunatic raving. Yes, it’s a text that calls for the mass murder of most men; it’s also a clear-eyed assessment of the utter ridiculousness of life under patriarchal capitalism. In conversation with Lizzie Borden at Anthology Film Archives this past weekend, Harron described Solanas as something of a Cassandra figure: damned to speak the future but never be believed.

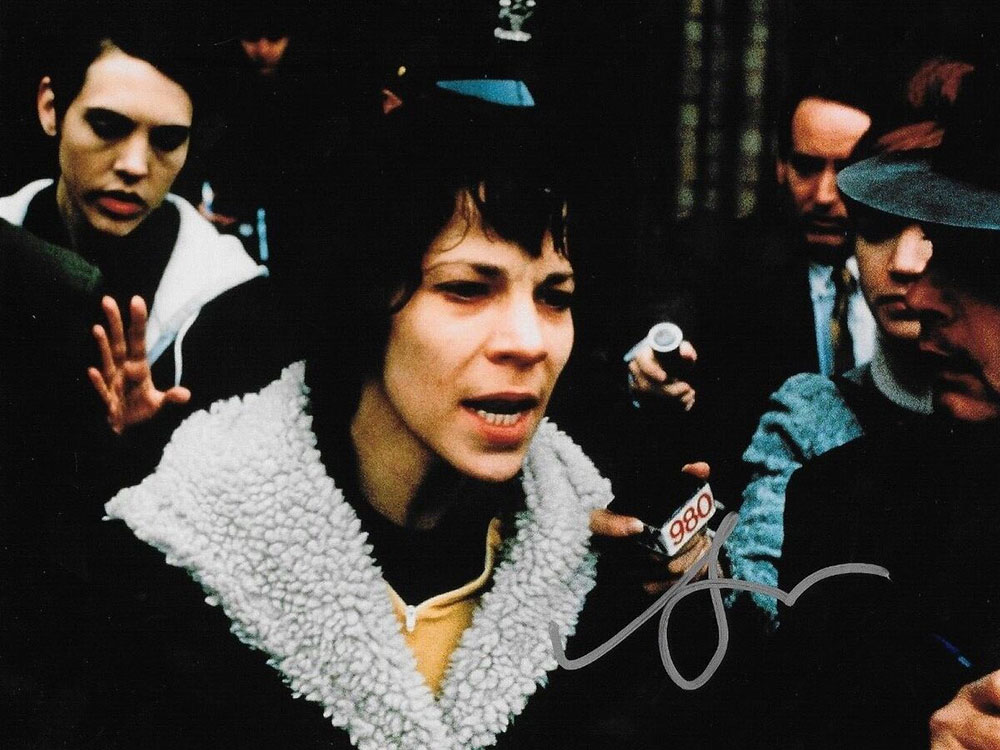

Released in 1996, I Shot Andy Warhol spoke the future, too. Harron’s first narrative feature, the film bears traces of what became an ongoing investment in sickos and loners, characters who find themselves at the fever-pitched fringes of their historical moment. More than that, I Shot Andy Warhol predicated contemporary interest in Solanas, who’s since been revived, for good or ill, by GWS courses and Ryan Murphy projects alike. Harron’s diligent research is largely responsible for much of what now comprises the Solanas archive (housed with Harron’s papers at New York University). But the film is as effective a drama as it is a document. Anchored by Lili Taylor’s flinty lead performance and patterned stylistically on Warhol’s own filmography, it’s got the kind of swagger Solanas herself—truly, as much an aesthete as Warhol ever was—might approvingly term low-down, cool, and funky.

It was also, like its subject, nearly lost to time. Long available only in a terrible YouTube rip, I Shot Andy Warhol is currently enjoying a rare theatrical run as part of Lizzie Borden’s “Unraveling Women” series at Anthology Film Archives. Screened on a nearly flawless 35mm print, the film feels unmistakably groundbreaking, even monumental—all the things Solanas wanted, and never quite got, to be.

In honor of the AFA screenings, I spoke with Harron about Solanas’s fraught feminist legacy, histories told from the margins, and the bullshit comforts of conventional biography. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jadie Stillwell: I Shot Andy Warhol is difficult to see nowadays. When’s the last time you saw it?

Mary Harron: Madeleine Olnek did a screening at IFC Center [in 2014], where she was asked to choose a favorite film, and I saw it then. I can speak to why it’s hard to see. I'm part of a group called Missing Movies which looks into all these independent films that have gone missing, in the sense of being unavailable, and it's taken about five years to trace what happened to I Shot Andy Warhol. Like a lot of independent films, it was put out by a company that went bankrupt. It was sold to another company that also went bankrupt. Three or four companies. All bankrupt. The rights and materials reverted back to American Playhouse and MGM has a claim on it, though I think we're hoping within the next few weeks to get a restoration deal sorted out. It was on a DVD, but it’s never been available on streaming, except in a bad YouTube edition.

JS: That’s how I saw it. It's a minor travesty that it hasn't been more accessible, because, at least from my perspective, Valerie Solanas has become more talked about in feminist circles in recent years, though no less notorious. Do you find that to be the case? Have you noticed changing conversations around Solanas since 1996?

MH: Certainly people reach out to me about my archive. I gave the Valerie Solanas papers to NYU and that's the aspect of my work people most want to know about—the research on Valerie that I did with Diane Tucker. But I would like to see the film be made more available, because I think its content, the ideas in it, or the issues, are more relevant now. I have two daughters in their twenties. They came to the IFC screening and they’d never seen it before. My older daughter was very pleased. She said, “You got all the politics right.” Because Valerie was kind of a TERF. All kinds of very visionary ideas, and then she had these deeply held prejudices and very essentialist ideas about gender.

She's a tragic figure in some ways. I think of her almost as an old school prophet, dreaming in the wilderness. And that’s not to discount her genuine craziness. But there is so much visionary insight into the workings of society in the SCUM Manifesto. It took many decades for people to acknowledge or come around to her vision of the absurdity of a society based on the inferiority of women. It's just astonishing, not unlike the racial dynamics in the United States, too. Vast amounts of people are considered inferior for no reason other than the need for the dominant group to stay dominant. But Valerie’s analysis is so funny. The way she talks about men as having all the feelings of gossipy women; they’re “shallow.” The way she's very tough on the women she calls “toadies,” women who collaborate in their own oppression. No one was saying this really, at the time. I mean, obviously there were feminist writings, but nothing as searing, in as few pages, as the SCUM Manifesto.

JS: Andrea Long Chu wrote a great piece for n+1 called “On Liking Women,” where she rereads SCUM Manifesto as, actually, a trans text. The essay gets at a lot of what feminism has long found difficult about gender expression and desire, among other things, but it's also just a great recuperative reading of Solanas. The way you describe Solanas’s diagnosis of society’s absurdity reminds me of Chu, who says that part of what Solanas brings to her political critique is aesthetic judgment. “Society is boring.” But you said you felt Solanas herself is perhaps more relevant now than she's ever been. Why do you feel that is?

MH: I just think young women are more interested in this kind of feminism. When I made the film, movie stars were not saying that they were feminists. When I started researching, it was like, “Oh, people don't want to know about this kind of angry woman.” I feel like there's been such a focus not just on feminism, but also on gender and what gender is, and on radical ideas about it of late, that it just seems much more of the moment than it did 30 years ago. I feel that a younger generation of women will be interested in the idea of revolution, because Valerie saw herself as a revolutionary. Being outside of, and antagonistic toward, your society holds appeal for a lot of young people, especially now.

JS: I'm curious how you first became interested in the project. I know it was originally going to be a documentary.

MH: I had worked for years in television as a researcher and I was working on a very prestigious British show called The South Bank Show that did hour-long documentaries about famous artists, most of them male. I was on my way to work when I saw the SCUM Manifesto in the window of a left wing bookstore in Brixton. When I started reading, I was really struck by it. By that point, I had interviewed practically everybody in the Warhol circle, including Warhol himself. I was the lead researcher on a big Warhol documentary, so I was completely immersed in the topic. I was amazed, because, apart from saying that she shot him and she was crazy, nobody had ever talked about Valerie Solanas.

So I had this idea for an anti-documentary. It was never going to be conventional. My thinking was, what if you took the most obscure person in this glamorous circle, and that most obscure, most despised pariah turned out to be the most interesting person of them all? What if you did a kind of reverse hagiography, where you take this person in the shadows and put them in the center? Now, how I was going to do that, I didn’t know. I just had this burning desire to make a film about her. I talked to [producer] Tom Kalin about how much would be the document, how much would be drama. Tom said, “I think it should just be a dramatic feature film.” I was unconfident about doing that, because I hadn't done a drama. He gave me a lot of confidence.

JS: I love the way the film stages readings from SCUM Manifesto as these highly stylized, black-and-white direct addresses from Lili Taylor to the camera. How did you decide that that would be the way to adapt the text?

MH: Fortunately, having been the researcher on a Warhol documentary, I'd spend an awful lot of time at the Museum of Modern Art watching Warhol films, including these famous black-and-white screen tests. Obviously, the screen tests are silent. It's just someone looking straight into the camera. But my idea was to take the design of the screen test and give Valerie a voice within it. I also wanted it to be separate from the rest of the world. To me, it was like Valerie's in heaven and she's speaking to us. I thought she should be very calm, very thorough, as opposed to the way she is in the rest of the film. Those scenes are her intellectual self speaking to us.

JS: How important was it to incorporate language directly from The SCUM Manifesto and Solanas’s other text, [the play] Up Your Ass, into the film?

MH: I mean, it's a film about a writer. Why do we know about Valerie? We know about Valerie today, obviously, because she shot Warhol, but also because of what she wrote, and the fact that in 1986, you know, I could find a copy [of SCUM Manifesto] in a bookstore. Of course, now there's many more copies in many more bookstores, but the fact that I was able to read it and get inspired by it is because she was a writer. So to me, that was very important.

JS: At the end, there's that note that says, since Solanas’s death, the SCUM Manifesto has become a classic radical feminist text. I read an Artforum review from ‘96 that really took umbrage with that.

MH: Oh, yes… People did dislike that. To be honest, it was not me who wanted that as the last line. I wanted a very deadpan last line saying that Solanas died in a welfare hotel in San Francisco in 1988. But these young women at Killer Films wanted to end on a positive note. I should have said, “Tough break, that’s ridiculous.” Occasionally, I give in to things and regret them, because that’s not what I'm trying to say. That's not what the film is. It's not making those judgments. It's a story; you can make your own judgments. I actually would love to change that last line.

JS: If it helps, I consider the authoritative ending of the film to be the last lines of dialogue that Lili Taylor delivers, the excerpt from SCUM that asks, “Why should we care about future generations? Why should we care about what comes after us?” Which negates the idea that she's become a part of some feminist canon, or is leaving any legacy at all.

MH: She's kind of a nihilist. I think the note at the end was an attempt to make the film more conventionally political and it's not. I have my own kind of fairly conventional politics, but that's not what my work is. I’m not trying to give a line. I’m uncovering and exploring aspects of history that deserved to be uncovered and explored. I felt a burning loyalty and devotion, in some ways, to doing this for Valerie. But that's not to say I'm trying to present her in conventional political terms or say everything she did was right. I just felt she deserved attention.

JS: Noticing and attending are political, too, but they’re definitely distinct from offering a referendum on someone’s overall significance. Lili Taylor's performance is especially wonderful in this context. It’s so detailed. Can you talk a little bit about the film’s casting?

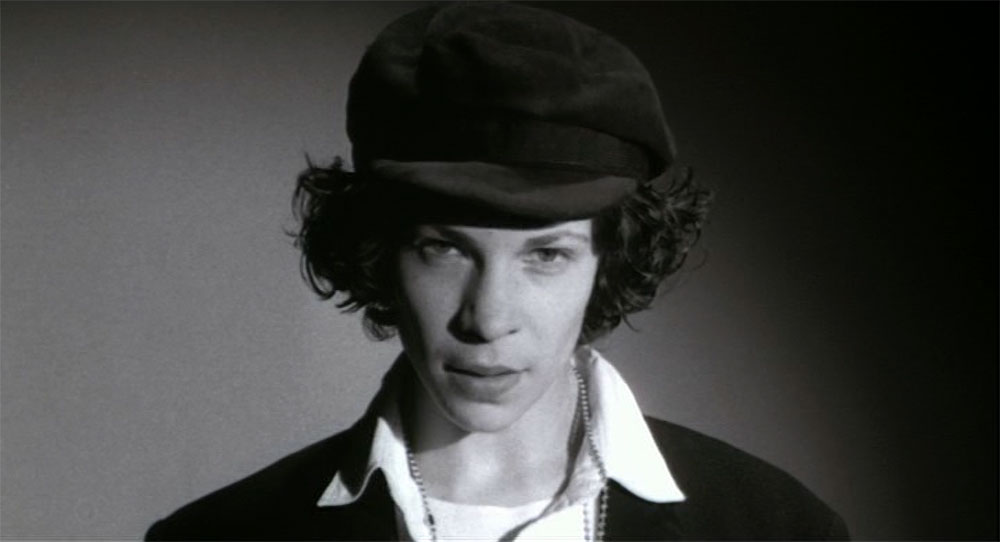

MH: Lili signed on before there was a script, when the film was still a 40-page document that I'd written out. After I saw her in Dogfight [1991], I never considered anyone else. She was such a remarkable actor. This was very early New York indie film days when there was much less pressure to cast a huge movie star. For Candy Darling, I almost cast someone who was a drag performer, Lily of the Valley, who had made the decision that they were not going to transition. But then Stephen Dorff expressed interest. Candy could pass as a woman, and Stephen really can't. But he is a very, very good actor. I mean, now you would cast someone who is trans—or maybe not, because Candy had not transitioned. I don't think of [Dorff’s performance] as physically successful, but I think emotionally it was very successful.

JS: Are you saying that, were you to make the film today, you would have wanted to cast a non-cis actor in Candy’s role?

MH: I understand that there would be a lot more people in various stages of transitioning. I would have a lot more choices.

JS: What about Jared Harris, who plays Warhol? How did he become involved?

MH: Jared came in and I had no idea who he was. He's one of the great underrated—actually, just one of the great actors of our time. When he came in, I thought he could really look like Warhol. And then he played vulnerability. A lot of people who came in for Andy were very caricaturish. They were snide, or they were sort of campy, or they were sort of disapproving of Warhol, which I never liked. I want people to love their characters. Jared played from the inside. He played a fragility and vulnerability and an elusiveness that was really great.

JS: What I like best about the film is that it doesn't pathologize the shooting or Solanas. The narrative moves backward from that event, almost in a criminal analysis mode, but there’s no attempt to offer a final explanation for it.

MH: I don't think there is one. Obviously, Solanas developed some kind of paranoid schizophrenia, but there are so many factors that go into it. There was being homeless, being poor, being without community or connection. I think mental illness is exacerbated by your physical existence, by living in a hard and precarious way. As you become a little crazy, you become more isolated. There's a brief thing at the beginning of the film where the psychiatrist is reading a report and says, “There was sexual abuse [in Solanas’s past].” But not everybody who was sexually abused tried to kill Andy Warhol. I kind of despise the whole biographical reading thing, the way it tries to find some magic key.

JS: A lot of your films focus on misfits or misanthropes. Where do you see the influence of this film in your other work?

MH: There’s a bit of it in [The Notorious] Bettie Page [2005], in the sense that I'm looking at women against a historical backdrop. In Bettie’s case, it was sex in the 1950s. For Valerie, it was revolution and art in the 1960s. For me, I’m interested in seeing these things play out through an individual life. Let’s take someone who has been despised by history, as Valerie was, and approach them with sympathy. For Bettie, she was a pin-up model, so she never spoke; I wanted to bring her to life. The other film [I Shot Andy Warhol] relates to is Charlie Says [2018], which is my film from Guinevere Turner’s script about the Manson family. Again, there’s the urge to locate a particular historical perspective with a limited number of characters who aren’t always given enough credit.

JS: When you’re considering a project, would you say you're motivated by opportunities to do deep historical research, to really set a particular period-based scene? Or are you drawn to individual figures first?

MH: I'm very interested in history. No story is just an individual’s story, because if you're doing a real life story, you can't separate the two. It's funny. I think people largely are not interested in history or historical backdrop. A lot of the time they want biography, they want explanation, they want psychology, which doesn't interest me, because I don't believe in the truth of it. I don’t believe you can make a clear psychological map to explain someone's life. I'm very interested in the forces that shape you beyond individual character and destiny—which are, especially if you're a woman, the time in which you live.

I think that if you're a woman of the 20th century, early 21st century, the year you were born will have an enormous impact on who you are and what you can become. My daughters will have a very different life than I had, and my mother had, or my grandmother had, and that's not so true of men.

JS: Storytelling in this mode is also a good way of moving away from a classically hyper-individualistic, neoliberal, American mentality.

MH: I’ve been criticized a lot for it. Especially with Charlie Says, which I really feel is one of my best things. People were very upset that I didn't give an explanation for why the Manson girls did this, and it's like, well, it's in the texture of the film! There is no single answer. I could have given more background information, but they all came from pretty long, different backgrounds, and nobody had the major trauma that would explain it. It’s not about that.

JS: Would it feel reductive to you to try to offer that kind of diagnostic reading of human behavior?

MH: Yes. Your parents got divorced, or your father didn't love you enough. A billion people have had that happen to them. They don't all end up killing strangers. I just feel it's simplistic. It's comforting to people because they want an explanation. I think that's the begetting sin of American Hollywood movies. They give people an explanation that they can live with for why things are the way they are.

JS: I think sitting with discomfort is probably better for audiences, across the board.

MH: Or sitting with some unanswered questions. It doesn't even have to be uncomfortable. You're not going to be spoon-fed an explanation for why, because there isn’t one. Sometimes I very deliberately don't put it in. Maybe I would do better, engage people more, if I did do that, but I say no. I think it’s intellectually indefensible to pretend that there's one simple explanation for how these things turn out.

JS: We do have to talk briefly about American Psycho [2000], both in this context of characters without explanatory psychology and because I don’t think we could get away with not talking about it.

MH: When we were shopping that script around, people would reject it and say, “Why don't you write more about his psychology, his family background, his traumatic childhood.” There's something in the book about some divorce. It doesn't matter. He's killed 49 people. His parents’ divorce really isn't relevant. His mother not being there for him really doesn't count. I resisted all that background, and I think that's one of the reasons why the film has lasted as well as it has, because it doesn't give you all that crap.

JS: Instead it allows audiences to read it as responsive to or representative of ills that aren’t unique to this individual.

MH: Bateman is everything crazy and psychotic about the Reagan ‘80s, or early 20th century American culture or capitalism. He's just refined it to a single person. I think that's the thing about giving a psychological explanation for someone like that, it almost lets you off the hook. “Oh, well, that’s because of that, that was him, that’s why it happened.” No. This is a crazy society. That’s what we’re looking at, on the whole.

JS: It’s the famous Fredric Jameson imperative, “Always historicize.” And it’s a continuous project. You don’t historicize just one time, or in just one gesture.

MH: I think there's something I just find intellectually untenable about the urge to explain everything. I’ve fought a lonely battle over it. You know, a lot of the time, my films don't get good reviews, initially. And yet, they last well, or they get another look later on, because they don’t conform to anything. I feel like that's my comfort. I refuse the urge to explain why people are the way they are, and I think my films have more staying power because of it. I don’t know. Maybe I'm just full of myself. Or maybe I’m right.

I Shot Andy Warhol screens tomorrow night, November 20, at Anthology Film Archives on 35mm as part of “Presented by Lizzie Borden: Unraveling Women.”