Saloum (2021) opens on a blue horizon made immediately ominous by the co-presence of the moon and sun and by a booming score; a narrator grimly intones, “Here, we say that revenge is like a river,” and a child drags a hefty gun and chains into the deep. Cut to a corpse-filled street in Guinea-Bissau where, as the on-screen text explains, the 2003 military coup d’etat “looks more like bloodshed” than order, particularly for the international drug trade. A hooded trio is introduced weaving rhythmically between bodies, pausing to blow white powder in a man’s face, breaking down doors, and emerging with a hostage and a suitcase whose contents inspire smiles all around. These are Bangui’s Hyenas: “Guns for hire, live by fire.” Less than five minutes in, and miles from the shores of its namesake locale, Saloum’s setting is established as a space in which contemporary political strife, past personal traumas, genre pastiche, the urban and the resort, created myth and “factual” folklore all coexist—sometimes peacefully (or at least humorously), sometimes to devastating effect.

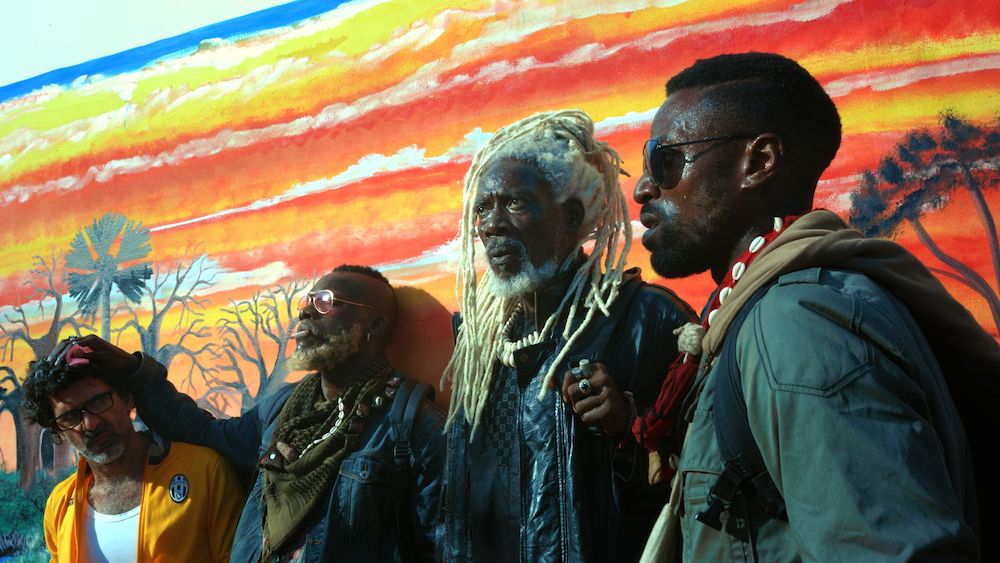

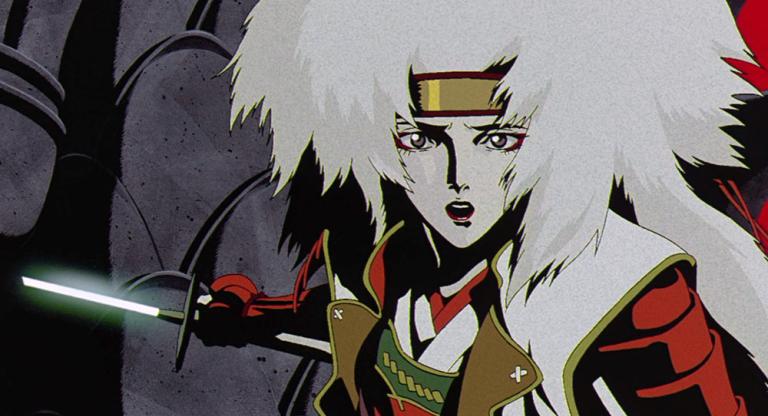

The Hyenas are legendary mercenaries whose exploits are late-night storytelling fodder for child soldiers “on crack,” according to the voiceover: Chaka (Yann Gael), the charismatic leader; Rafa (Roger Sallah), buff, gruff, and dressed throughout in sunglasses and leather loafers; and Minuit (Mentor Ba), a magician and seer, whose shock of white dreadlocks appears in stark contrast to the intoxicating blues and greens of the delta. Beautifully in sync whether swinging cleavers or slinging Dante and Thomas Sankara quotes, the trio has escaped to the Baobab “camp,” a collection of huts near the shoreline in Sine-Saloum, after discovering a leak in their getaway plane’s fuel tank. Their fellow holidaymakers include the “artist couple” Younce and Sephora, as well as Awa (Evelyne Ily Juhen), a Deaf woman who converses at length with the Hyenas in sign language. Each small detail, from Chaka’s red leather gloves to Minuit’s warning of “eyes” on the group, blossoms as Saloum’s rapid-fire genre shifts—from crime drama to melodrama to horror film—progress.

According to writer-director Jean-Luc Herbulot, the film was inspired by a trip with producer and creative partner Pamela Diop to the Sine-Saloum Delta in Senegal. One of the last pre-colonial African kingdoms (which only became part of Senegal in 1969), Saloum combines the “paradise and hell” of the river and the desert, per Diop. The delta contains a UNESCO World Heritage Site and, as Herbulot has explained, its own “myths and curses” and singular black magic, as well as the scars of desertification and other trauma. The expanses of river and sand that serve as a living backdrop for the film recall the tumbleweed- and promise-filled landscapes of American westerns, whose fertility propagated foundational myths and histories of violence—much like the harvest reaped by our ill-fated mercenaries in the creature-feature portion of the film.

Saloum’s symbolism is rich if vaguely defined and its plot delightfully convoluted, making for a hyperkinetic 80 minutes full of the sort of visual storytelling that makes extended explanation unnecessary. Produced by Herbulot and Diop’s Lacme Studios on a very limited budget (“five weeks in the desert without computers or internet,” according to the director), Saloum offers a powerful counterpoint to the miasmic slog of most Hollywood genre filmmaking.

Saloum screens tonight, May 28, at BAM as part of “FilmAfrica 2022.”