Although it is Spain’s largest film festival, San Sebastián is considered to be a younger cousin to Berlinale and Cannes, at least according to avid festivalgoers I met in the Basque city. In some ways, it’s true: the festival runs hastily on the tails of the late-summer Venice and Toronto, and many world premieres come from these four larger festivals for a reprise, which operates on a much lower budget than its European and North American counterparts. But San Sebastián can also veritably claim that it has championed the likes of filmmakers such as Pedro Almodóvar—whose debut feature, Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980) premiered at the 1980 edition of the festival—Bong Joon-ho, Walter Salles, and the Coen Brothers. Beyond its Official Selection, San Sebastián boasts several strands of note, among them sections that push boundaries in lesser recognized ways, perhaps even more so with Berlinale’s elimination of “Encounters.”

I promised myself I would devote time to the festival’s proud and lesser-highlighted focus on Basque cinema, programmed as part of “Zinemira,” but I found myself carried away by many of the bold and exciting new directorial voices on their first or second features in the “New Directors” section, even when their unexpected choices didn’t always land—for one, I prefer a film that takes failed risks rather than takes none at all. I capped off the festival with some screenings from the open-ended competition section “Zabaltegi-Tabakalera,” which includes films of varying lengths in addition to video-installations and other forms of media. I also made sure not to miss the distinctive festival section that pairs food-themed films with curated haute cuisine dinners, “Culinary Zinema.” Uniqueness became the name of my festival game.

Due to growing confrontations in my own life, I found myself irrevocably drawn toward films replete with existentialism and grappling with popular portrayals of death and mortality. Befitting this self-guided theme was an early morning screening of François Ozon’s Quand Vient l’Automne (2024), a wake-up call confrontation with mortality that set the tone for the festival. The film follows an elderly woman during retirement in the Burgundy countryside. Like several of Ozon’s previous films, it explores death head-on. Filled with home-cooked meals, long walks in the woods, and a warm color palette in which characters appear to physically gleam in the sunlight, the filmmaker’s very cozy new feature is neither despondent nor pitiful. I was, at first, frustrated by Ozon’s plodding pacing, in which characters are rarely given time to grieve as death is unexpected yet entirely commonplace. However, I quickly learned that this is not out of a lack of compassion, but instead to make way for a tale of two active, aging women turning over a new leaf in an autumnal era of life. I learned that I was looking at the story through the lenses of my rose-colored naïveté.

The festival’s “New Directors” section included features that were both contemplative and melodramatic, spanning polar opposites on a spectrum of films about death. Sylvia Le Fanu’s coming-of-age tale My Eternal Summer (2024) is a well-wrought and accomplished debut feature. It is about a 15-year-old girl named Fanny and her final season of youthful freedom, which is burdened by pre-death grief responding to the terminal illness of her ailing mother. Le Fanu shows that to love Fanny is to know her, achieving a delicate and difficult-to-achieve balance between Fanny’s aggrieved teenage self—she acts out in a bid for attention from her boyfriend—and her grieving heart, where she is forced into premature adulthood through circumstances out of her control. The film strikes a chord as it reminds me, in an unexpected way, of an all-time personal favorite: Céline Sciamma’s Water Lilies (2007). Both are set within a circumstance where its 15-year-old female protagonist is unavoidably alienated from her peers due to a constant preoccupation. In Sciamma’s debut, it’s unresolvable desire, while in Le Fanu’s debut, it’s unresolvable mortality.

As their sophomore feature together, after the Un Certain Regard selection The Desert Bride (2017), Cecilia Atán and Valeria Pivato presented La Llegada del Hijo (2024) in the “New Directors” section. The film follows a single mother, Sofía, receiving her young adult son from four years of rehabilitative incarceration after he kills his former swim coach with a car. The filmmaking duo seeks to explore the clash between a mother's social contract to unconditionally love her son when he stands in the way of her own desire for romantic love and sexual connection. Initially, La Llegada del Hijo emulates the tone and tropes set forth by similar films about the complicated and unpredictable relationship between a mother and her troubled son, such as Lynne Ramsey’s psychologically intense We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) and Xavier Dolan’s more playful Mommy (2014). But this changes with a juicy reveal that the filmmakers hint at through the first half of the film. Sofía’s grief is immense and all-encompassing, and soon we learn why. Unfortunately, Atán and Pivato fail to use the plot twist to further cross-examine the parental relationship. Instead, the film loses focus by lingering on sensual yet empty underwater imagery, rather than much-needed moments that contextualize the origins of Sofía’s mourning. By the end, it’s easy to understand her positionality, but much harder to take it to heart.

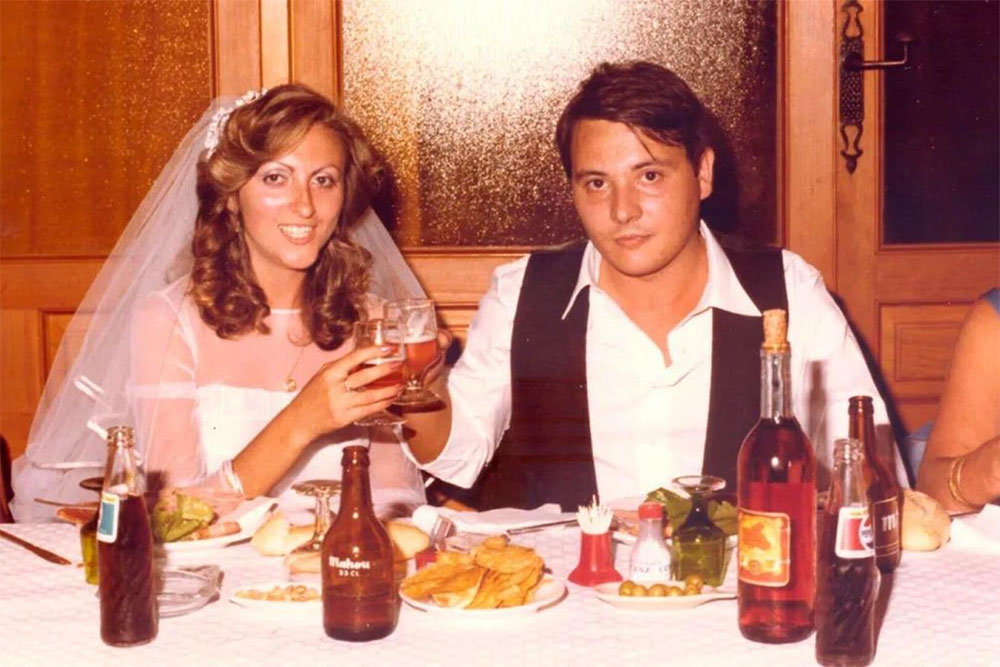

A “Zabaltegi-Tabakalera” standout was Elena López Riera’s 40-minute documentary short Las Novias del Sur (2024, pictured at top), which is set against the personal context of her unmarried, childless self making the film at the age when her mother had children. Through honest, humorous, and at times delightfully libertine talking-head interviews, López Riera comes face-to-face with the greatest joys and regrets of several elderly women. The straightforward yet emotionally evocative interviews traverse the entangled institutions of heterosexual marriage as both a celebration and the death of adolescence, sexual pleasures and disappointments, and the expectation for women to bear children. The film’s simplicity in how it cleverly plays with juxtapositions is its greatest strength: whereas one woman declares that her marriage was her life’s deepest regret, another gushes that she found the (now late) love of her life as a septuagenarian, with wild sex to boot. Older women, López Riera seems to say, contain more than multitudes. To underestimate them is to make a mockery of their experiences and every lesson they’ve learned.

The “Zinemira” strand featured several of the festival’s hyperlocal selections, based in and around the Basque province of Gipuzkoa, where San Sebastián (or Donostia, in Basque) is located. Arantxa Aguirre’s film Ciento Volando (2024) acts as a tribute to the renowned late Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida, who crafted the three-piece Peine del Viento anchored to the oceanbound rocks on the northwestern side of the city. The iconic work of art is one that visitors to Donostia, including myself, make an effort to pass at least once—its twisted, rusting pieces of steel challenged daily by the furious crashing of waves. Aguirre’s narrative device, of a young woman seeking answers about the sculptor, quickly becomes unnecessary as subjects speak so fervently about Chillida. The film’s most meaningful moments come offhand as captured on camera, such as fleeting shots of park-goers happily taking pictures with his many sculptures: art contextualized anew for a constantly refreshed public. This also allows Aguirre to play creatively with his visuals, integrating nature-themed imagery amidst pleasantly didactic long conversations. “I think Chillida’s relationship with nature has a trace of romanticism,” says one subject. The filmmaker’s refusal to solely focus on the artist as a subject, instead also framing him as a product of his space and environment, encourage, or perhaps forced, me to reflect on my positionality as a writer, a non-Basque individual, and someone estranged in my own relationship to nature—myself a mere sheep in the reinforcement of the anthropocentric human-nature dualism.

Erreplika (2024) by Pello Gutiérrez starts out in a form similar to Lea Hartlaub’s essay film sr (2024)—oneiric and tracing together disparate parts—before morphing into a focused intellectual meditation on the Virgin of Zukuñaga, a precious 13th century religious sculpture whose unsolved theft became a source of trauma for the Gipuzkoan town of Hernani. Gutiérrez’s film is a pastiche of historical photographs, conversations, dramatic readings of texts, and archival material from his father, always surprising in its eclecticness. Through voice-over and by attempting to understand the collective memory of the sculpture, Gutiérrez questions the community's fixation on finding the “original” work, even though several replicas have been made and worshiped just the same. Near the end of the film, he brings to the fore the idea that “original” can suggest something that stays “true to its roots” but also something “different” and “novel,” a word that seemingly contradicts in its temporal meaning. However, this insight comes far too late to be examined in a satisfying way, save for further musings on the human obsession with symbols and the ways in which we endow meaning.

Through two films and a curated dinner, setting off my final days at the festival was my engagement with the “Culinary Zinema” section, which daringly encourages viewers to think of cinema beyond time, sound, and visuals. In Mugaritz: Sin Pan ni Postre (2024), Paco Plaza takes a close look at the R&D process behind the cuisine at the famed experimental and oft-controversial two-Michelin-starred Mugaritz, located just outside San Sebastián. The chef, Andoni Luis Aduriz, pushes his team to disregard diners’ pursuit of a hedonistic, sensual experience. Dining at Mugaritz means putting aside even the alimentative value of food which, upon reflection, is a considerably privileged position to be in. In haute cuisine, as in art, Aduriz says in the film, customers seek a Rubens or Van Gogh and at the restaurant are instead, to their displeasure, met with a Rothko or Pollock. To him, however, that’s the goal.

From Mugaritz, it's easier to see what the culinary arts can offer back to the cinematic. After attending the “Culinary Zinema” dinner curated by Argentine chef Paulo Airaudo, whose restaurant Amelia is a fine dining staple of Spain, I needed to talk to someone who works with a completely different medium. Airaudo loves to watch films across all genres and styles: “Food is the same; it’s about the culture,” he says. It’s less about what it is and more about how it comes to be, he continues: “why you eat it and what you understand about it.”

Airaudo doles out an apparent but invaluable lesson for popular film criticism regarding the importance of history, context, and appreciation of cinema beyond the bindings of genre labels. The parallels between film and food grow, as he explains that fewer people are trying a variety of different international cuisines, whether in their own home or at restaurants. The same can be said about the viewership of world cinema: even as film from around the world becomes more accessible, when commercial and mass-marketed flicks dominate the interconnected global film industry, the urge to pick the most easily digestible films can be overwhelming. Making the choice for something different, unexpected, or even uncomfortable uplifts chefs and filmmakers alike.