“I actually don't know that much about Elaine May. But I'm an ACE member and I love [Metrograph’s] programming, so I was like, ‘Oh this is a great opportunity to learn about this legendary figure.’ And this was such an amazing introduction,” said Joanna Naugle, who attended Metrograph’s recent screening of May’s feature Mikey and Nicky (1976). It was part of “ACE Presents,” the theater’s ongoing programming partnership with American Cinema Editors. Multiple workers at the theater confirmed that the showing, open only to ACE and Metrograph members, sold out minutes after tickets were made available. That’s unsurprising; this was an exceptionally rare opportunity to see the filmmaker in person.

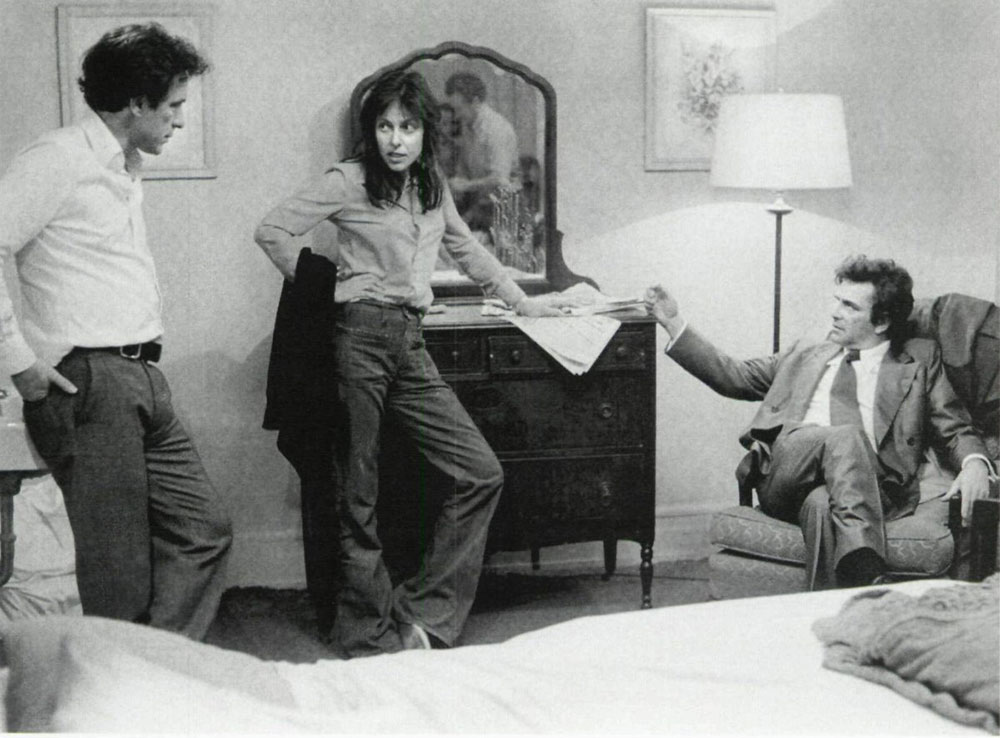

Speaking with Joanna and her fellow ACE member Evan Wise after the screening, I used their mutual admission that they hadn’t seen any of May’s other films as an excuse to recommend they watch all of them. As millennials, they were exceptions among ACE’s cohort, whose presence meant the event’s audience skewed much older than one typically sees at Metrograph. The result was a mix of industry professionals and fans, people who have been familiar with May for decades (or even worked with her), those who have become fans relatively recently (like myself and my seatmate, director Isabel Sandoval), and neophytes like Joanna and Evan. Steering the proceedings for a Q&A after the film were two ACE members who have collaborated with May: her friend Phillip Schopper and Jeffrey Wolf, an assistant editor on Mikey and Nicky.

The reclamation of May’s films, long underestimated or outright dismissed, has been hard-fought but deeply satisfying for her appreciators. It’s happened piecemeal, gradually but surely accumulating momentum in the 21st century. Lincoln Center hosted May for a retrospective in 2006, and The Harvard Film Archive did the same in 2010. May was surprised by Ishtar (1987) receiving a far warmer reception than it had historically at a 2011 screening at the 92Y, and the film hitting Blu-ray in 2013 prompted Jessica Kiang to revisit May’s career. By Richard Brody’s accounting, a 2016 screening of the film with May in attendance performed similarly well. That year, she also returned to television, directing an American Masters episode on her erstwhile comedy partner Mike Nichols and acting in Woody Allen’s Amazon Prime miniseries Crisis in Six Scenes—one of the premium examples of streamers throwing money at creatives without any idea what they wanted amid “Peak TV.”

In 2017, a top declaring “Written and Directed by Elaine May” became one of the early hits in the burgeoning auteur T-shirt fad. Seeing noted May booster Quentin Tarantino wearing the shirt during an interview was a surreal bit of Film Twitter cross-pollinating with reality. (In retrospect, this trend foretold the current climate of merch-frenzied, cinephilia-as-a-lifestyle brand consciousness embodied by film world entities like A24 and, well, Metrograph.) That same year, A New Leaf got a Blu-ray release courtesy of Olive Films. Things ramped up in 2018, as May returned to the stage for a celebrated turn in the revival of Kenneth Lonergan’s The Waverly Gallery and won a Tony Award. In 2019, Mikey and Nicky, beautifully restored in 4K, joined the Criterion Collection, and Film Forum ran a May-focused retrospective. Earlier this year, Carrie Courogen’s biography of May came out. But despite this ever-rising appreciation of her talent, May cannot escape production difficulties; the latest word on her return to directing, Crackpot, is that she needed a shadow director to proceed, for insurance purposes.

We’ve come a long way from Ishtar being a minor pop culture punchline while May’s other films were left out of the conversation. Sandoval told me how that film’s reputation was what led her to discover May in the first place; morbid curiosity as a gateway to appreciation. Ishtar is one of the more annoying examples of a movie garnering a reputation for being “so bad it’s good,” particularly in the early internet snark era, thanks to received wisdom rather than anyone actually watching it on its own terms. Gary Larson posited the movie as the sole VHS available in Hell in a 1991 Far Side cartoon, only to offer a rare apology when he actually watched it years later and enjoyed it. The snag in the narrative was always that Ishtar is honestly fucking hilarious.

Notably, the collective reevaluation has come almost entirely without the participation of the artist herself. May oversaw the restoration of Mikey and Nicky, but even with the increasing enthusiasm for her films, she has rarely broken the public silence she’s maintained since 1967. Courogen could not get May to speak to her for her biography. Given the filmmaker’s elusiveness, it’s appropriate that the book is titled Miss May Does Not Exist.

The mystique of May’s long-standing withholding from the press and masses may be part of her appeal. Going back to her days as a stage comedian, her output has been characterized by subtly interlacing layers of irony, absurdity, and sincerity. A New Leaf might have a true love story buried beneath its blackhearted murder plot. Mikey and Nicky is a bone-weary look at friendship that trudges toward a tragic conclusion with an inevitability that May compared to the conventions of Greek drama after the ACE screening. Her refusal to explain herself, and her preference to let her films do the talking for her, has left critics and audiences to glean their own readings—for a long time with a bias toward trepidation and now with much more goodwill. I was not privy to any of this firsthand, but there were apparently rumblings in the lobby prior to the event’s start over whether May would in fact show up.

If anyone came to the Metrograph screening hoping to clear away some of the mystery, I can’t imagine they walked away satisfied. One of the first things May said during the Q&A, when Schopper referred to Tarantino relating an anecdote that she supposedly shared with him about the inspiration for Mikey and Nicky on his podcast, was a deadpan, “Well, Tarantino will say anything.” She was similarly wily throughout the 40-minutes or so of discussion. When asked about “finding the characters and story” in the editing process, she glibly replied that “Movies, although edited, are also written. And you look at what you wrote [when editing] and think, ‘Ah, it’s that scene!’” In a testament to how well she can still work a crowd, the audience burst into hysterics at both those sentences in sequence. The conversation was marked by such evasions disguised as jokes. Some of it may also be down to the mental looseness that comes with age; an audience member had to help her recall Bugsy Siegel’s name, and at one point, she referred to how we would see what she was talking about “if” we watched Mikey and Nicky, apparently forgetting a screening had just happened.

Rest assured, though, May is still sharp, especially for a 92-year-old. To me, one of the more striking moments of the discussion was when she mused on the Greekness of the story and its inspiration in the world of Chicago crime she was familiar with in her youth: “In this world, when you've stolen something, when you know a hit is on you, you know the guy they’ll call to set you up is your best friend…. But [Nicky] calls [Mikey] anyway…. They always call their best friend…. When money was gone, you took for granted that the guy [you decided took it] was guilty, and the guy who took it always kind of knew you'd find out. And he couldn't leave town…. It was like faith…. They always stole, and they always got shot.”

Schopper and Wolf did not pull much, if anything, out of May about the production of Mikey and Nicky that isn’t already known. That doesn’t really matter, though. Anyone can read about that tortured production from any number of sources. May still has a presence—quietly authoritative, sometimes riotously funny with just a few well-jabbed words—that makes her rapturous on stage. It’s the same quality evident when I saw her in The Waverly Gallery. If only she came out for us all more often. In the meantime, I hope she gets to make Crackpot.