What do Screwballs (1983), Loose Screws (1985), and Screwball Hotel (1988) have in common? Besides being unforgettable titles with iconic VHS boxes, they were all directed by one of the most prolific and singular maestros of the 1980s “sex comedy” genre: Rafal Zielinski. While his career has spanned a wide variety of styles, budgets and audiences, his name will forever be linked to those late night cable TV programs, like USA Up All Night, that specialized in horny R-rated B-movies.

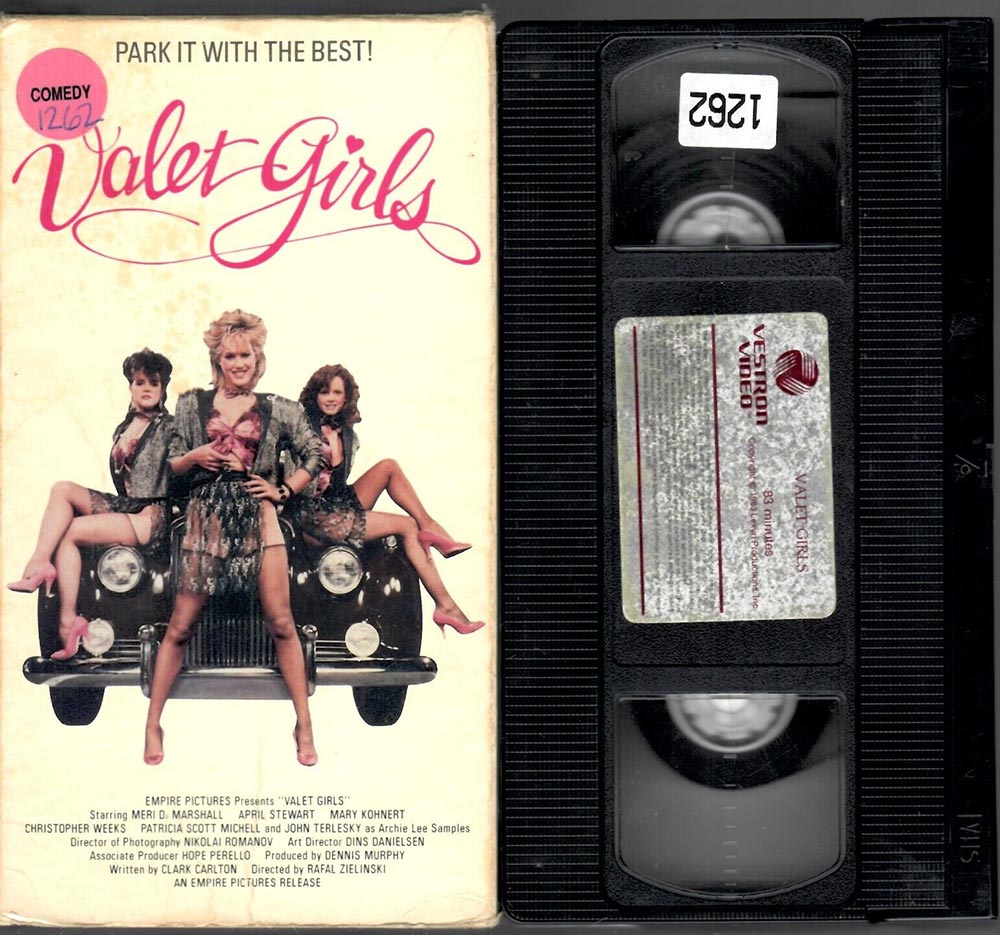

Tonight, The Deuce film series at the Nitehawk Cinema in Williamsburg, Brooklyn will present an ultra-rare 35mm print of his 1986 cult classic Valet Girls (1986). It’s the story of three female parking attendants struggling to find footing in Beverly Hills. In the face of predatory entertainment executives, and a rival male valet crew called Fraternity Parking, the ladies fight for survival in a world of hedonistic house parties and expensive cars.

I Zoomed with Zielinski last week as he prepared to drive down from Canada for tonight’s screening. The word “fun” came up numerous times in our conversation. It’s an essential aspect of his process, philosophy, and output. He even made a drama called Fun (1994) that premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, and still feels the pain of his first Hollywood project Fun Park falling apart. Needless to say, I had a lot of fun chatting it up with the legendary auteur.

Michael M. Bilandic: When Roger Corman passed away a couple months ago I read all these obituaries talking about how he launched the careers of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, James Cameron, and all these other big names. You’re one of the directors who got started working with him, too. Maybe we could begin with your relationship to him?

Rafal Zielinski: He was definitely one of my main mentors. He was my film school, in a way. Earlier, I went to MIT to study art and technology, but it was frustrating. The computers back then were so primitive. What you have on a little iPhone now was a ten-story building then and to code anything you had to literally punch cards. It turned out, they had this wonderful documentary film department, though, run by Richard Leacock, who was the founder of cinéma vérité. You know, the movement with D.A. Pennebaker? So that's where I lived and hid out. He just gave us a camera and said, “Here, go and film.” It was about observing life.

MB: So Richard Leacock is really where it all started?

RZ: I would say he was my number one mentor. But then I came to Canada to make my first feature, Hey Babe [1980], thanks to the Quebec government. It was such a nice story. Buddy Hackett played a down-and-out vaudeville performer living in a Broadway theater as a squatter. And this girl we found was incredible, Yasmine Bleeth. She was like eleven. It was filmed half in New York, half in Montreal, because it was done through the Canadian tax shelter system. It was a beautiful art house film that led to a Hollywood film that I set up called Fun Park, another story that I spent many years developing. It was a very sensitive coming-of-age story, about a group of teenagers growing up. Then the studio changed heads and they basically got rid of me like one week before shooting, just because there was a regime change. It was a devastating experience.

MB: A good friend of mine in L.A. had that happen to him recently. You hear it all the time. It sucks.

RZ: It completely destroyed me. I felt totally raped and violated by Hollywood. Then Roger Corman came knocking, saying he was doing this comedy in Toronto. I felt so disillusioned. So I just grabbed any job I could get.

I felt worthless because of that Hollywood experience so when Roger came with this film called Screwballs, I just said, “Wow, I'm so depressed. This will take me away.” I jumped in. It was like a crazy, wacky comedy. It was interesting meeting Roger. The reason he hired me was because he saw the Hey Babe trailer and said, “Kid, you're hired. You're visuals—I love them. You’re in.” It was a very quick decision.

I met him in Toronto and he felt like a professor. He wore a suit and tie, and was not what you’d expect. He was a very intellectual, very elegant, very refined man. He gave me three rules. He said, “Number one, you have to cast beautiful, interesting people, because it's all about the actors. Rule number two, if you're filming an actor and you put them in the corner of a room, you don't point the camera into the corner with the corner behind the actor. No, no. You put the camera in the corner and you put the actor in front, so you get the whole room. That's production value. Your whole job is to maximize production value.” And then, he gave me another rule. He said, “This is a teenage comedy. I need twelve shots of naked breasts.” And I said, “Oh, my God." I was so shocked, coming from this professor… But since all these great filmmakers had started with him I said, “I'm just gonna do this.” And I had so much fun shooting this crazy comedy.

MB: So it got you out of your depressive state?

RZ: Yes and no. I thought it was my way to re-enter Hollywood and finally triumph. But it was actually a very bad mistake, because I got labeled as a guy who started in art house and ended up in B-movies. And that led to the sequels: Loose Screws and Screwball Hotel. I find those films a total embarrassment. I cringe when I think about them. But I just felt like, “I'm gonna make the best of it. I'm gonna make them as great as I can and have as much fun as possible.” I saw them like Archie comics. I had studied comic book art and had a storyboard artist on Screwballs. We drew the whole movie like a comic book, and that became the style of the movie.

MB: I just rewatched A Bucket of Blood [1960], which Corman directed. It’s set almost entirely in one beatnik coffee shop. It doesn’t have twelve shots of boobs, but it follows the other rules. Your 1986 classic, Valet Girls, which is about to screen here, is also pretty much a one location comedy set in a Beverly Hills mansion. What was the genesis of it?

RZ: I went on a trip because the Canadian government gave me money to research a movie I wanted to make in Venice, in Italy. On the road, I stopped at the Cannes Film Festival and met this guy, Charles Band, who had this crazy company called Empire Pictures. He saw the trailers for my Roger Corman comedies and said, “We’re looking for a director. We need a director. Come to Hollywood. Can you be there in a month from now?”

What happened was that he had something like a $50 million bank loan—I think from Paribas—to churn out hundreds of movies. It was incredible. They would just come up with one idea, one paragraph, and then hire a writer and make a movie. It was like a factory. So I left for LA and they gave me the script for Valet Girls.

They came up with the concept at a party where some girls were doing the valet car parking. They said, “Ok, that's a great story. I love these girls. They look cool. They’re beautiful and young. Let's create a movie.” They hired a writer, and in one week they had a script. It was actually written by a gay writer and he was really cynical about Hollywood. I loved his cynicism—I had just gone through this horrible Hollywood experience of getting totally screwed on Fun Park. I related to it.

MB: Valet Girls is a real indictment of Hollywood culture and the entertainment industry as a whole. The villains in it are all perved-out producers.

RZ: I would dedicate this movie to Harvey Weinstein. It’s all about him. It’s a feminist film, because in the end, the girls win. That's what I love about it. They overcome these sleazebags.

MB: An antagonism toward Hollywood’s culture and power has been a staple throughout your career, even though I know you still want to make Hollywood films. I watched a video, from a while back, on your YouTube channel called Hollywood in Flames [2013]. It was of you burning the posters for the top three films at the box office that week: Man of Steel, Iron Man 3 and Despicable Me 2. You’ve always managed to go a long way with a fraction of their budgets and resources. How many days was the Valet Girls shoot?

RZ: It was super fast. Twelve days, if I remember correctly. And it was mostly one location.

MB: For a shoot that fast, and with so many constraints, what was the energy like on set? I’m always curious, on comedies, to hear if everyone’s stressed out, volatile, and overworked, or if they’re joking around, having fun, and improvising?

RZ: The energy was really fun. I loved it. It was like a party. It was a little bit inspired by, what's his name, Peter Sellers? It was sort of a challenge having all these crazy characters. My cameraman was the son of Joseph von Sternberg, Nicholas von Sternberg. He was so funny and had these stories about his father and all the horrible experiences he had in Hollywood. So he related to it and I related to it. We were like these two pals, hidden behind the camera— “Let's do this. Let's make fun of this moment.” We really pushed all the buttons.

MB: Did you go to a lot of parties in L.A.?

RZ: I did when Fun Park was being set up. It’s where I met all these lazy producers who ended up betraying and getting rid of me. These are all the guys I hated so much. In a way, I was getting out my anger and frustration at them. But, at the same time, I love art and my whole goal was to make art house films and huge Hollywood films, so I tried to sprinkle whatever art I could. Like with the rock band. I tried to find the most avant-garde art band I could. You know The Fibonaccis? I put them in.

MB: I was unfamiliar with them, but they’re perfect.

RZ: And we had Meri D. Marshall as one of the leads. She came in and the role was for a singer, and she already had a whole career as a singer. She was such a light in the movie. She was so enthusiastic, so much fun and such a wonderful talent. I think she went on to have a bit of a career. But, you know, these careers are not easy.

I always try to not go the conventional route. Like when I was at MIT, I had a project where I was trying to do a movie based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. It's my life’s dream to turn it into a mainstream movie so I had William Burroughs writing the script and…

MB: William Burroughs was writing the script for your student film?

RZ: Burroughs was writing the script, yeah! I mean, it was really cool. And Philip Glass was doing the music, when he was totally unknown. I found him when he was doing the Robert Wilson opera in Brooklyn. He was a plumber at the time. We met in his apartment and he had greasy hands. He just had come back from a whole day of plumbing and he was composing in the middle of the night. It’s like the Swedish composer Christopher Nolan uses today. Now everyone’s trying to not go the traditional, John Williams, route. They're interested in composers who have never worked in film before.

MB: You worked with Dread Zeppelin in National Lampoon’s Last Resort [1994]. That was a pretty non-traditional score.

RZ: That's right. That was another one. And Willie Dixon. When we did Ginger Ale Afternoon [1989], he was a famous blues man and had never done a movie before. But I loved his music, and I said, “Listen, this movie is like the blues. Listen to the dialogue. The dialogue is your lyrics. Now, play each scene over and over in the studio and improvise to it.” And that's what Willie did with his band. They would listen to the dialogue and the harmonica, and the guitar, would weave through underneath the dialogue and become like an improvisation.

![Heavy Metal Summer [also known as State Park, 1988]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Heavy-metal-Summer.jpg)

MB: The Love is Like a Chainsaw scene with Ted Nugent in Heavy Metal Summer [also known as State Park, 1988] is one of my all time favorite musical numbers in a comedy. What was it like working with “The Nuge”?

RZ: It was actually really cool. He was very, very, very professional. I was surprised. You know, he's this, sort of, wild, rebellious rock-and-roller. But he came in and did his set—he was very nice and very professional. Same with Adam Ant. After I did Valet Girls we hired Adam Ant to star in the next movie I did for Empire called Spellcaster (1988), which was shot in Rome. He was the star. What a joy to work with.

MB: The castle where you shot Spellcaster is in Visconti’s The Leopard [1963] and it’s also where Tom Cruise married Katie Holmes, right?

RZ: The Castello Orsini-Odescalchi. That's right.

MB: The Loose Screws soundtrack is in a league of its own.

RZ: That was my idea to do a song called… What was it called?

MB: “Do the Screw”?

RZ: Yes! I said, “Let's create a dance called ‘The Screw.”’ We hired a choreographer and a local rock musician. “Let's Do the Screw!” That was crazy.

MB: And the theme song, “Loose Screws (Breakin’ Away)” by Errol Francis, and the Francis Factor is unreal. I had to rip an mp3 of it from the opening credits since it was never released. I play it all the time.

RZ: I'm working on a new movie about a fourteen year-old girl who is a singer, an Irish singer who's sort of a Billie Eilish type who reconnects with her father, who is a down-and-out rock-and-roller. I have a whole list of rock stars I want it to go out to, all the way from Keith Richards, who would be like the very old guy, to younger ones like Father John Misty or Devendra Barnhart. That’s the next movie I'm working on, which is also a music film.

Then, I'm also working on a movie right now called Ecstasy, which is based on a diary that this girl wrote about how she got hooked on the drug ecstasy. The whole movie is about the electronic dance music scene. It all takes place in EDM clubs so I'm talking to a lot of DJs about that. I love the connection between music and film and art.

MB: I’ve been dying to ask you about National Lampoon’s Last Resort [1994].

RZ: Yes?

MB: What was it like working with Roger Clinton? Casting him, at that moment in time, is unbelievable. It would almost be like if Hunter Biden randomly did a bizarro comedy for Tubi today. How did you snag the president’s hard partying, tabloid prone, half-brother for a scuba instructor-themed Two Coreys movie?

RZ: Bill Clinton was President and we heard that his brother was a comedian. So we said, “Let's call him. Let's get a hold of him. It would be really cool to have, you know, the president's brother in the film.” He came in and did great. I said, “Wow! You know, you're in man.” We wanted it to be fun. When he arrived, there were all these secret service guys all around the set. It was a surrealistic experience. I said, “Let’s really make fun of him. Let's really go all the way. Make it as crazy as we can.”

MB: The Zubaz weightlifting pants and midriff World Gym shirt was a perfect wardrobe decision.

RZ: We let him completely make a fool out of himself. And he did. I just pushed the buttons. It was great. Only in America. I tell you, only in America.

MB: When you were working on these films did you have any sense of the lifespan they might have?

RZ: I thought that they were my entry into big Hollywood movies. But it's funny, a lot of them are becoming cult films. When I met Quentin Tarantino… He's a fan… “Oh, Mr. Screwballs.” He bows down and I’m like, “Can you just shut up. Don't even mention it. You know, man? Keep quiet. I'm really embarrassed about these.”

MB: I was thinking about ‘80s sex comedies earlier and there's a genre of music called mallwave…

RZ: Like Mallrats [1995]?

MB: Kind of. It’s an offshoot of vaporwave. It’s like retro, synthy, easy-listening music, but they play vintage VHS found footage of shopping malls over it. Like, clips of kids, blissed out, hanging at the mall. It elicits a nostalgia for something most of the artists never experienced. These malls look utopian to them and everyone’s happy, perusing their favorite stores and looking good.

Your comedies can create a similar feeling. Everyone seems to be having a blast, partying, and getting laid. And they’re made with an irreverence that’s hard to imagine in our contemporary, discourse-throttled landscape. What’s your take on the 1980s? Do you have nostalgia for that time?

RZ: Yes. First of all, I loved the disco era, which was just before the ‘80s. That was such an exciting, explosive period. And then when the ‘80s come, you get punk rock and new wave. Politically, the country was a little bit like it was under Trump. Everyone was like, let's just have some fun while all this shit is going on. It was an interesting time for film.

MB: When I was researching Valet Girls last night, I noticed there's actually a vaporwave type band called Valet Girls now.

RZ: It's very trendy. A lot of filmmakers are using things from that period, VHS tape and low tech. They love vinyl and celluloid. It's all this nostalgia.

MB: Speaking of celluloid, where did the Valet Girls print play when it was released?

RZ: I don't think anywhere. I think it played at the American Film Market, but basically went straight to video, and then the company went bankrupt. I don't know what happened. These movies go on crazy journeys.

MB: And now it’s finally opening in New York. When’s the last time you saw it?

RZ: It’s been 30 or 40 years, and I’ve never even seen it on the big screen! So it’s almost like I’ll be seeing it for the first time. It'll be fun. I hope it’s not faded.

Valet Girls screens tonight, August 8, at Nitehawk Williamsburg on 35mm as part of the series “The Deuce.” Director Rafal Zielinski will be in attendance for a Q&A.