In June 2022, the artist Shirin Neshat produced the photo series and two-channel video installation that would become her exhibition The Fury. In large framed photographs hung low on the wall, women of various ethnicities and body types face the camera in shades of nudity. Hair falls past shoulders. Persian poetry by Forugh Farrokhzād is inscribed as calligraphy on the surface of the photo paper, in some places densely layered so that letters and diacritics partially veil the subjects or resemble bruises.

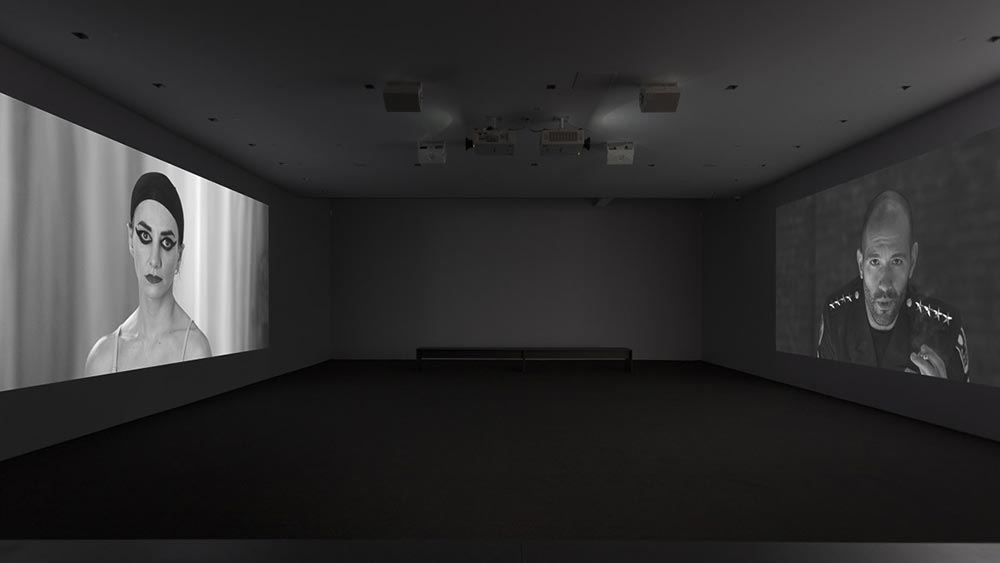

In the video, a young woman wearing a black wig and sormeh eye makeup on one screen faces off with a uniformed man smoking a cigarette on the other. The frames widen and she appears undressed, encircled by military men in a cavernous hangar or gym. A Persian song about freedom, sung in Arabic by Emel Mathlouthi, scores the woman’s hypnotic dancing. At first her bare skin is unblemished, but a turn of the melody reveals wounds, clarifying her victimhood. According to the artist, The Fury developed from her “obsession with the psychological trauma of women who survive sexual assault . . . especially by authorities in prison systems.” Neshat’s work imagines these women living a shattered existence, in which the boundary between illusion and reality blurs and the distance between assault and exile collapses.

Later in the video, hallucinatory perception further fractures with a long gaze out of a residential window. The cut to a street scene and then screaming banshees shot in infrared are reminiscent of Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) or a vision by Leonora Carrington.

Since the 1990s, Neshat has been celebrated for stylized portraits and films that cast female bodies as eroticized sites for violence, poetry, projection, and pride, often focusing on women who stand under political pressure on the threshold of madness. Neshat’s early work depicted veiled, gun-toting Iranian women, and has become an institutional face of art-world protest that some believe reifies an Orientalist gaze and propagates an image of Iran that current protests insist upon breaking.

Three months after The Fury was completed, Mahsa Amini was killed in the custody of the Iranian Morality Police, who accused the young woman of improperly veiling. Her murder spurred the Woman, Life, Freedom protests in Iran. Neshat’s new work exists in a strange tension with that women-led movement. Neshat asserts that she has “never been interested in presenting truth or reality or [in] pretend[ing] like I know something about Iran. My work has always stood in that poetic, surrealistic, conceptual basis . . . and is not limited to Iran.” The artist has now lived in the United States longer than she lived in Iran, and the new video is shot in Brooklyn.

Neshat cites histories of sexual abuse in Iranian jails but notes that the military uniforms in her video do not contain national identification and could be “the Nazis, the Russians, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards.” Of course, they could also be Americans. The Mathlouthi song the prisoner dances to has become a symbol of the current uprising, and has been sung by Iranian women who have since been executed. The Fury betrays conflicting pressures to distance Neshat’s work from contemporary reality and to meet the commercial obligation to create politically engaged art for a Western audience.

By updating the image of the protester from veiled militant to jailhouse odalisque and by disidentifying her subjects as always Iranian, Neshat both invites and attempts to repel criticism. In the past, the subjects in Neshat’s work have been noted for their rebellious silence. Now, perhaps, they are getting louder.

The Fury is on view at Gladstone Gallery through March 4.