Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (1997) contains an ironic music cue: The Crusaders’ “Street Life” backs Pam Grier as she arrives at the Del Amo mall. The American shopping mall was developed in opposition to urban downtowns. In the new post-war order, dirty, dangerous, “blighted” city streets were rejected in favor of clean, controlled, meticulously designed interiors, and the mall established itself as the default commons for rapidly expanding suburbia. In Anthology Film Archives’ “Shopping Worlds” series, no film better articulates this antagonism between city and suburb than Dawn of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1978). When a zombie incursion forces them to flee Philadelphia and head for “the sticks,” four runaways lock themselves inside an abandoned shopping center. In a set-up that satirizes the logic of early mall developers, infested cities may have devolved into zombie feeding grounds, but life is still possible inside the mall. To survive, the characters block every entrance and exit, turning their hideout into a fortified enclosure. This mall-turned-barracks is a clear indictment of exclusionary suburbs and their hostility toward anyone beyond the white middle class demographic for whom they were built. For Romero, suburban malls are where “street life” goes to die.

And yet as malls grew up, mall culture provided a compelling substitute for the energetic streets that Randy Crawford invokes in song. Shot by a band of NYU students in 1983, Mall City documents a day at Long Island’s Roosevelt Field mall, which serves as a vibrant public arena thanks to its hordes of teen visitors. The mall’s biggest draw is unambiguously its thriving pick-up scene. Much of the film unfolds as a flurry of amusing comments about where the cute girls hang out (“you find a lot of them at Burger King”), and the state of teen dating (“mall relationships don’t last”). In their man-on-the-“street” interviews, the filmmakers wonder whether the mall is a homogenizing force in youth culture. Yet elsewhere in the series, the mall fosters a lively ethos of rebellion and delinquency. Films like Chopping Mall (Jim Wynorski, 1986) and Mallrats (Kevin Smith, 1995) capture various modes of teen troublemaking, though Wynorski’s campy tale of private policing is a grimmer take on the mall’s relationship to youth than Smith’s goofy tribute to triumphant losers.

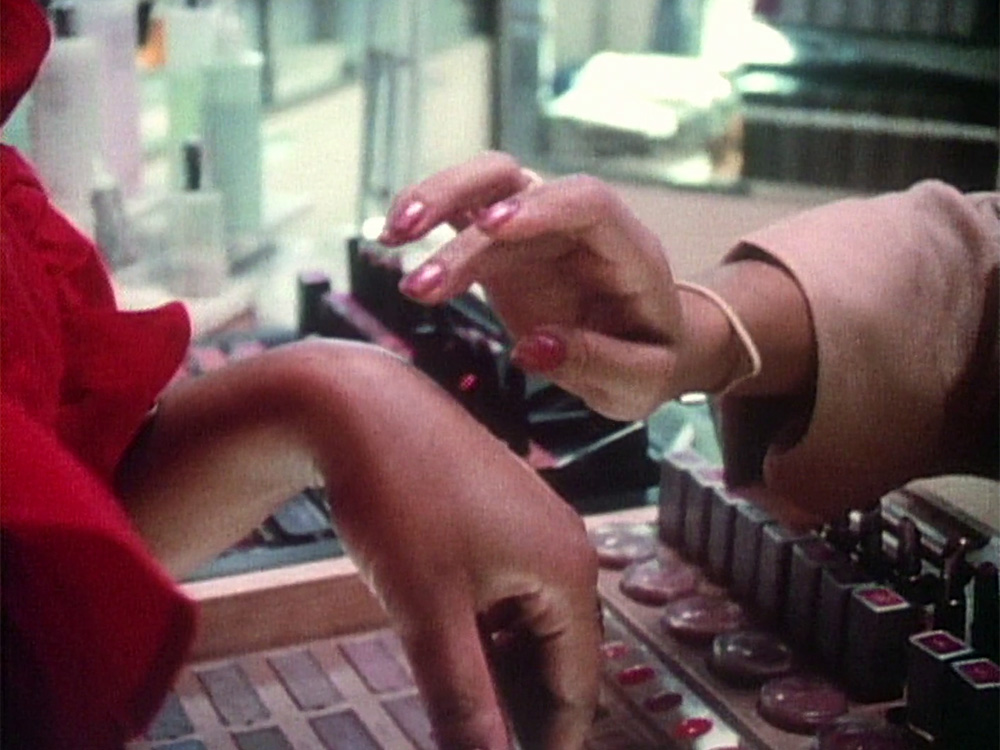

Teens and zombies are both subversive elements in the mall, as neither constituency has much interest in buying things. They come to see people, or eat them, but not to spend money—a premise staunchly objected to in the opening of Frederick Wiseman’s The Store (1983). “We’re not a place to come in and get out of the rain, we’re not a place to come visit and socialize,” says a Neiman Marcus employee during a staff meeting at the luxury department store’s Dallas headquarters. Stores aren’t grand civic spaces: they exist to make sales. Wiseman follows this dictum with a two-hour immersion in the appealing gestures and textures of a fancy store. Fingers trace shiny jewelry; ladies coo over silky furs; salespeople speak sweet nothings to their customers (“You are so special,” “You look fabulous”) in soft Texan accents. These moments accumulate into a mesmerizing sensory experience that recalls certain styles of ASMR YouTube content. The Store just might be the incidental ancestor of countless videos with titles like “Sleepy ASMR Shopping Trip” or “ASMR Luxury Watch Shop.” The “Gruen transfer”—named for father of the mall, architect Victor Gruen—is a psychological process that afflicts shopping mall patrons: the mall atmosphere lulls them into senseless buying through a mix of confusion and pleasure. It’s often difficult for ASMR-heads to explain the sensation of ASMR to the uninitiated, but pleasurable hypnosis comes pretty close. It’s the Gruen transfer adapted for the screen, a way to lose oneself in a lush, materialist dream.

The twenty-first century has not been kind to malls. Their commercial and cultural importance, once paramount, continues to slip. More malls were constructed in the 1970s and ’80s than their local economies could ultimately sustain, leading to a spate of dead and dying malls all over the country. As these buildings close, the communities they served lose their town squares, and people turn to a different commons: the internet. Now, instead of running errands, people-watching in the food court, or killing time at the arcade, you can go online and leave a comment on a dead mall video lamenting the loss of these rituals. The “Shopping Worlds” series incorporates this dimension of mall culture with an “Urban Exploring Internet Videos” program, a salute to the wildly popular video format that brings heavy virtual traffic to these empty structures.

The internet is troublesome in some of the same ways malls are; both can feel like democratic, public spaces until their private owners remind us they are not. But the digital realm has some advantages over the architectural. Where adaptive reuse for these buildings is slow, expensive, and onerous, creative reuse is cheap and fast. Cecilia Condit’s Possibly in Michigan (1983) is another entry in the series that has become deeply embedded in the internet lexicon. After being picked up on TikTok in 2015, Condit’s avant-garde horror-musical-comedy has spawned a whole new genre of content on the app. The story follows two women being stalked by a cannibal while perfume shopping at the mall. On TikTok, the video’s creepy, catchy melodies accompany short sequences where young women lip-synch the characters’ absurd dialogue while they apply makeup, smell perfume, or carry out bizarre performances. With #possiblyinmichigan now accounting for 102.9 million views, the app has delivered alternative culture to the masses in much the same way malls did for the suburban kids who were otherwise cut off from diverse cultural scenes. While we wait to see what happens with the abandoned shells that dot the American landscape, movies, internet videos, and social media present possibilities for reinterpreting the mall, processing its legacy, or simply relishing in its strange spectacle.

“Shopping Worlds” runs August 2–17 at Anthology Film Archives.