Film at Lincoln Center and the Locarno Film Festival’s retrospective, “Spectacle Every Day: Mexican Popular Cinema,” presents 22 films made from the 1940s to the 1960s that showcase the dominant themes and filmmaking style of this particularly rich moment in Mexican cinema. And yet, the retrospective isn’t merely a collection of the greatest hits. The series does not include the María Félix star-vehicle Enamorada (1946), or its director’s other canonical hit, Maria Candelaria (1944). Ismael Rodríguez’s curriculum staple, We the Poor (1948), isn’t part of the series either and neither is Luis Buñuel’s most famous film from his time in Mexico, Los Olvidados (1950). Instead, “Spectacle Every Day” includes titles such as Chano Urueta’s occult-horror flick The Witch’s Mirror (1962) and René Cardona’s The Batwoman (1968), which is no more, and no less, than a Batman rip-off.

Because certain filmographies are over-represented in culture-at-large—sometimes, when I browse repertory theater calendars, it seems as though only the United States, France, Japan, and Russia make movies—their most admired films and filmmakers have developed a cult of interest around them that has motivated countless writing and programming dedicated to everything that inspired them and they have influenced since. Savvy filmgoers aren’t just familiar with the French New Wave or New Hollywood, but its origins and many tributaries. As far as Mexican cinema is concerned in New York—and I suspect, much of the United States—its luminaries and treasures remain terra incognita for all but specialists and over-consumers. This ignorance, combined with the retrospective’s distance from its temporal focus, accounts for its seemingly unconventional selection.

Although “Spectacle Every Day” does not include María Félix, Emilio Fernández, Ismael Rodríguez, or Buñuel’s most famous, or best regarded films, all of these talents are represented in the retrospective. In fact, the films of theirs that are included in the series, in addition to the many other films in the retrospective, are more representative of mid-century Mexican popular cinema than their most celebrated works. What “Spectacle Every Day” demonstrates is both a rigorously researched take on a major moment in Mexican cinema and a ruminative approach to historiography. The retrospective does not conform itself with the classics nor does it cushion itself by exclusively showing qualitatively good films; instead, its wonderful mix of genres, budgets, and politics advocate for a new understanding of Mexican cinema and the culture that produced it, which is in itself brimful of wild actors and saturated by enduring traditions and ideologies.

The twenty-or-so years in Mexico that this retrospective concerns itself was one of immense changes. It was a period of modernization during which long-held religious, political, and social beliefs were contested. The country was in flux—rural citizens migrated to cities, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) tested out new political directives, secularism was on the rise, and the nation’s youth embraced love and sex (taking a cue from the hippies north-of-the-border.) Although this time period has long been defined by the Mexican Miracle that saw a swell of economic prosperity among the country’s middle-class, what the cinema from this era reveals is a population in a state of crisis. The reactionary streak in films such as Alejandro Galindo’s The Mind and the Crime (1961) and Rodríguez’s The Three Garcías (1947) gestures at a citizenry in fear of its own transformation. And, the conflation between women and crime in Streetwalker (1951), and extraordinary evil in the case of both Rogelio A. González’s Skeleton of Mrs. Morales (1960) and Urueta’s The Witch’s Mirror, reflects the paranoia of a country losing its grip on machismo in much the same way The Three Garcías and The Batwoman’s belittling of their female characters represent a doubling down on patriarchal tenets. Most, if not all, of the films in this retrospective feature crisis plots, with characters that are torn between city and country, science and religion, tradition and progress, crime and compassion, the past and the future. Take Me In Your Arms (1954), a decades-spanning melodrama directed by the revered filmmaker Julio Bracho, might be the only of these films to feature all of these dilemmas.

Take Me In Your Arms stars Ninón Sevilla, whose charisma and beauty remain unrivaled in cinema history, as Rita, the daughter of a fisherman who is exploited by several men as she tries to rid her father of his debts. The film immediately sets up a contrast between the merry townsfolk of Rita’s village and their greedy, urban counterparts. In the opening scene, the former are seen dancing to live music in celebration of a sudden surplus in caught fish while the latter attend their festivities in a state of solemnity, as though incapable of tolerating, or understanding, their fortune. When Don Antonio (Julio Villareal) asks Rita’s father to send her off with him so that he can pay off his debt, and Rita, having eavesdropped, decides to abandon her one true love, José (Armando Silvestre), and follow Don Antonio to secure her family’s well-being she does not only lose her beloved and her community, but her status as a respectable woman in the eyes of her village, which immediately casts her as an opportunist and a traitor.

Rita’s future success as a movie star, along with her involvement with a well-to-do politician in Mexico City, can be seen as a natural extension of this break; after all, her status as a soubrette would have been considered immoral in her village and her attachment to a big-city politician a further sign of betrayal. The film’s major drama—the romantic push-and-pull between Rita and José at different points in their lives—embodies the intense whiplash Rita endures from the moment she decides to follow Don Antonio, the same disorientation felt across the country by people willing to make it big in the city and those they left behind. The nail-biting scene of seduction that comes at the end of Take Me In Your Arms further emphasizes this dangerous disjunction, as Rita and José stare at each other over the course of an entire night from two separate couches that are only a few feet apart. Their prolonged silence and inaction, sustained despite their evident love for one another, marks the acuteness of their new emotional, class, and geographic distinctions. Sitting across from one another, they can no longer communicate.

Something much funnier, and sinister, is at play with language in Fernando Méndez’s The Suave One (1951). Roberto “El Suavecito” Ramírez (Victor Parra) smuggles little bits of English into his sentences. Early on, when his neighbor Lupita (Aurora Segura) asks him why he disappeared over the weekend, he replies, “Tuve que arreglar un business. No pude dejar escapar el chance.” (I had to fix a business. I couldn’t let the chance escape me.) His mannerisms, and his zoot suit, indicate his wish to be a gangster, like those in the films of Howard Hawks. But this wish, however childish, is indicative of something larger at play in Mexican culture at this era: the influence of American culture.

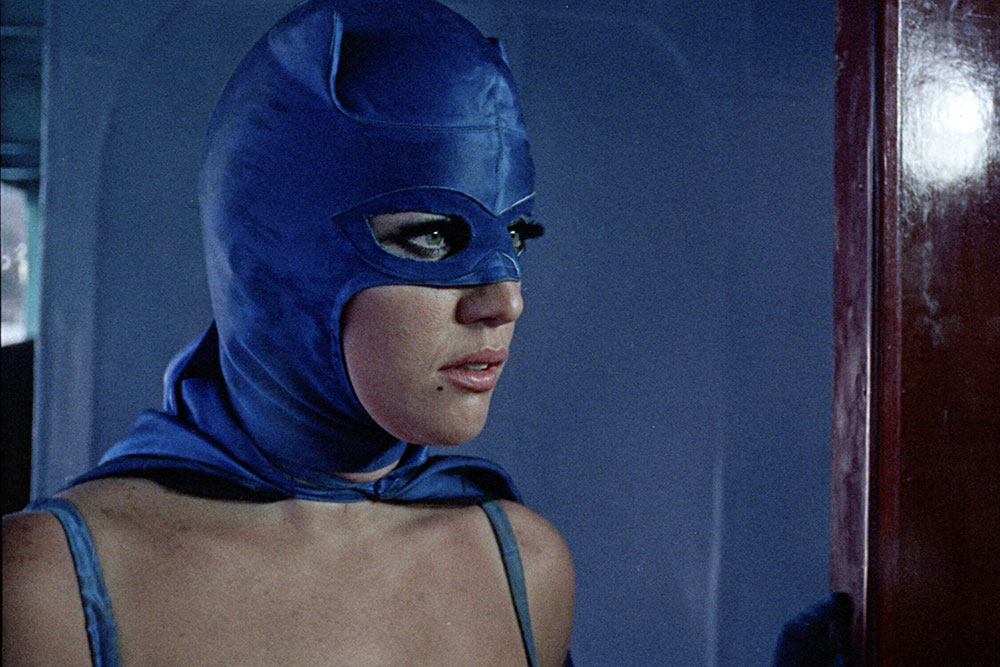

The most blatant example of cultural signifiers spilling down south in this series is The Batwoman. Made by the genre maestro René Cardona, whose son Cardona Jr. and grandson Cardona III are also responsible for some of the gutsiest gems in more recent Mexican cinema, The Batwoman stars the Italian actress Maura Monti as a wealthy woman who moonlights as a bat-vigilante. Although the look-and-feel of the film is ripped straight from Adam West’s Batman, there are a million oddities that make it so much more than a simple lark.

The Batwoman’s indecision about whether it’s a superhero film, a spy flick, a detective thriller, a luchador movie, or a sci-fi enterprise is what makes it such a delight, with its genre cross-pollination showing just how reliant Mexico’s popular cinema was on successful genre models elsewhere. The appearance of the Gill-man as one of the film’s main villains halfway through its runtime is evidence enough about how this form of uninspired hand-me-down cinema could actually stumble upon sublimity. This blend of genres, tropes, and actors from around the globe on the Mexican silver-screen is either a reflection of Mexican filmmakers’ adeptness at reworking global sensations with local color or Mexican audiences' need for an imported identity.

The Three Garcías, a film about three rival cousins contesting for their American cousin Lupita’s (Marga López) love, suggests Mexicans at this time were enamored, albeit begrudgingly, with Americans. As the three charro cousins try to woo Lupita, they play down her Americanness and tell her marrying one of them will reveal just how Mexican she really is. The film, which aligns itself with traditional views over its entire runtime—the cousins’ grandmother, Luisa García (Sara García), repeatedly voices her belief that men must learn how to fight with their fists, get married, and have children—plays up the Garcías’ Mexicanness by having them dress in their charro outfits throughout most of the film. Lupita, for whom Mexico’s cowboy pomp is new, even praises her cousins’ outfits and the macho connotations they carry. But, when her cousin Luis Antonio (Pedro Infante) invites her to dance, he goes out of his way to show off his English and says, “I love-eh you.” Charro-suit on, Mexican pride aside, he cannot help but speak a little bit of English.

The Garcías’ pride is the product of generational fighting among their family members, an inherited meanness that sustains their tough and stubborn attitude—a psychology of preservation. Luis Buñuel’s The River and Death (1954) also concerns a longstanding village dispute. Its plot revolves around a Hatfield-McCoy-like feud that’s reached its last two victims: the erudite city doctor Gerardo Anguiano (Joaquín Cordero) and the vengeful Romulo Menchaca (Jaime Fernández). Their opposing views on the vendetta that’s been left for them to settle—Anguiano, the man of science, suggests they forget about the whole thing whereas Menchaca, a family man, is always on the lookout for an opportunity to spill blood—correspond to fears about how Mexican society was split between a backwards rural population and a progressive urban population in the ‘50s. But, ever the subversive, Buñuel reminds viewers in The River and Death that this polarized fear is made-up and that his two leads, despite espousing different views about what direction society should head in, act in response to the same social pressures as everyone else. For Buñuel, the propensity to murder is the same among city-dwellers as it is among villagers, an inexplicable instinct he elaborated upon the following year with 1955’s The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz.

Fear of murder, and crime in general, is the reason Alejandro Galindo’s self-financed The Mind and the Crime (1961) exists. Galindo made a name for himself with standard, albeit thoughtfully detailed, dramas inspired by real-life people and events. Although The Mind and the Crime was ostensibly based on a real-life murder, its far-fetched claims about the psychology of serial killers and its use of life-like miniatures and models, alongside some bizarre tableaux, to recreate scenes from a grizzly crime place it in a wavelength of its own. The film’s visions of flying skulls and beautiful close-ups of fingerprints, all of which coalesce into a psychedelic painting in motion, are almost enough to distract you from its message: that the urge to kill is a primal instinct tied to devil worship and most common among the morally depraved denizens of big cities.

This fixation with the occult—still present in contemporary Mexican cinema, although from a compassionate rather than mean-spirited perspective—is most present in Urueta’s The Witch’s Mirror, a true gem in the retrospective that somehow manages to harmonize Häxan (1922) with Eyes Without a Face (1960) in under 80 minutes. Unlike The Mind and the Crime, which points the finger at satanism to explain an upswell in crime, The Witch’s Mirror inverts matters by making its villain a man of science trying to best nature and the supernatural. For Urueta, the unknown horizon of science represents a far more dangerous prospect than the historically misunderstood logic of the occult. While the ghostly Sara (Isabel Corona) looks spooky as she glides around the gothic mansion most of the film takes place in, it’s Deborah (Rosita Arenas), who is subject to multiple surgeries throughout The Witch’s Mirror, that elicits fear in her various states of medical distress—wrapped up like a mummy before a major surgery and scarred by fire that makes her look like Marco Ferreri’s Ape Woman. Here, science is framed as the enemy, as a yet-to-be-understood field-of-study capable of producing nightmares. And although Urueta’s film is full of nightmarish schemes and visuals, there’s also an irrefutable beauty in its compositions and narrative design. Alternately horrifying and alluring, always hypnotic, The Witch’s Mirror is a mishmash, a wondrous constellation of differences that mirrors the open-minded design of “Spectacle Every Day.”

Spectacle Every Day runs July 26 - August 8 at Film at Lincoln Center.

gd2md-html: xyzzy Fri Jul 26 2024