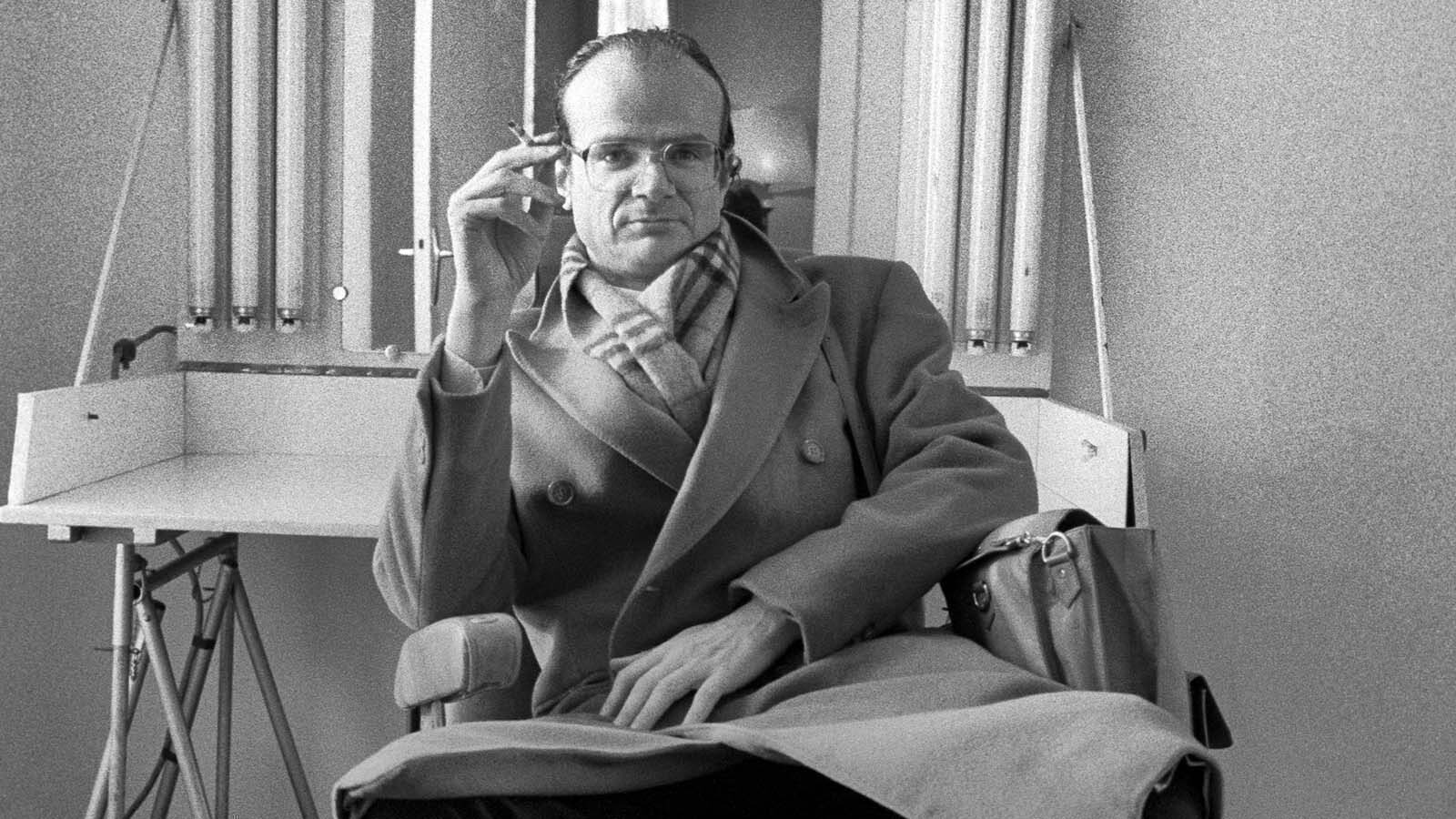

Serge Daney’s first book of film criticism was published in Paris in 1983 as La Rampe. In his introduction to the book, Gilles Deleuze praised Daney for his reflections on the most political period of Cahiers du Cinéma, where Daney was a co-editor from 1973–1981. Named for Daney’s ruminations on the row of footlights at the base of a cinema screen that divides the screen from the audience, the book is a remarkable collection of daring, lucid, pun-filled prose that allows the reader to see Daney’s thought taking shape.

Semiotext(e) recently published an English-language version of Daney’s book, translated as Footlights by Nicholas Elliott, a former New York correspondent for Cahiers du Cinéma. In celebration of the book’s publication, Elliott has co-programmed “Never Look Away: Serge Daney’s Radical 1970s” with Madeline Whittle at Film at Lincoln Center. I spoke with Elliott about Daney, whose death Jean-Luc Godard once claimed was the end of criticism, and whose writing practice Elliott likened to “squeezing words for every bit of juice that they have.”

ML: What drew you to Serge Daney?

NE: Serge Daney has always been the most important film critic in my personal pantheon, which is no different from saying that he’s one of the most influential intellectuals in my reading life. I’m also realizing as I get older that he’s been a life model in the way he rejected careerism and made choices according to his enthusiasms and friendships. I got into film when I was a teenager living in Luxembourg, so the film criticism coming from over the border in France was a big influence. About a year after I started reading Cahiers du Cinéma, they did an entire issue devoted to someone I’d never heard of and who had just died of AIDS: Serge Daney. An entire issue of tributes to him, including from filmmakers who already had this incredible aura in my eyes: Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, Philippe Garrel, Robert Kramer, Marguerite Duras, Alain Tanner, Wim Wenders. It was so striking to realize that these people who shaped a certain kind of film that I wanted to be a part of were bereft at the loss of Serge Daney’s voice. I understood their grief when I started reading his books. Chantal Akerman’s long-time editor and collaborator, Claire Atherton, said it best recently when I asked her what Serge Daney meant to her. Very spontaneously she replied, “He was like an ally.”

When I heard that Semiotext(e) was translating Daney’s books, I got in touch with editor Hedi El Kholti. Over the course of a single phone call, he asked if I’d like to translate La Rampe. I still can’t get over it.

ML: Did you have specific goals with how you approached the translation?

NE: Daney’s voice has a real literary quality. So my hope, and I assume Hedi’s too, is that having the book translated by one person, in book form, creates a unity of tone that might be missing from the many translations of Daney’s work that have been posted online by a variety of true believers who have worked on these complex texts, presumably without remuneration and often collaboratively, driven solely by the need to share the writings of Serge Daney.

ML: The program at Film at Lincoln Center is an exciting, almost obvious extension of the book. How did the program come together?

NE: Obvious is the word. While translating the book, I thought of a screening series featuring every film it mentions, because it’s a relatively slender volume. That appealed to me, both because I wanted to see these films in the theater and because in their various ways they all embody a kind of mule-headed formal and ethical singularity that I describe as “hardcore.” Films that are nearly frightening in their rejection of compromise. That goes even for the most accessible films in the program, like Tati’s Trafic [1971], which basically has no dialogue but gets across a deep perspective on technologically advancing Europe in the 1970s. I pitched the series to Florence Almozini at FLC and was thrilled to learn her colleague Madeline Whittle was interested in programming the show with me. Maddie was familiar with Daney’s later work, but was just discovering Footlights. It was inspiring to hear her get fired up about it.

Ultimately, we decided to focus on sixteen features and a short, about 75% of the films discussed in the book. The films we’ve chosen give a vivid sense of Serge Daney’s perspective on that moment in film history.

ML: How did you choose the title for the series, “Never Look Away”?

NE: We were struggling with titles that sounded like seminars at third-tier universities. So I turned back to Footlights and hit this sentence: “The shame of having seen and said nothing comes with a challenge to see everything, to never look away from anything, to acquiesce to the most aberrant adventures in cinema.” I didn't even have to finish the sentence to know we had our title. That instruction to “never look away” applies to all the films we’re showing and gets to the heart of Daney’s thought: Don't look away from reality. Don't look away from difficulty, from what frightens you. In Footlights, Daney writes about being frightened by the live attractions at the movies asking for money when he was child and being ashamed of it. He responded by learning to never look away. I find his ability to keep looking and make sense of what he’s seeing heroic.

ML: This writing and the films are so relevant now. In response to Godard’s Here and Elsewhere [1976], featuring Palestinian liberation fighters, Daney wrote about reparation and restitution.

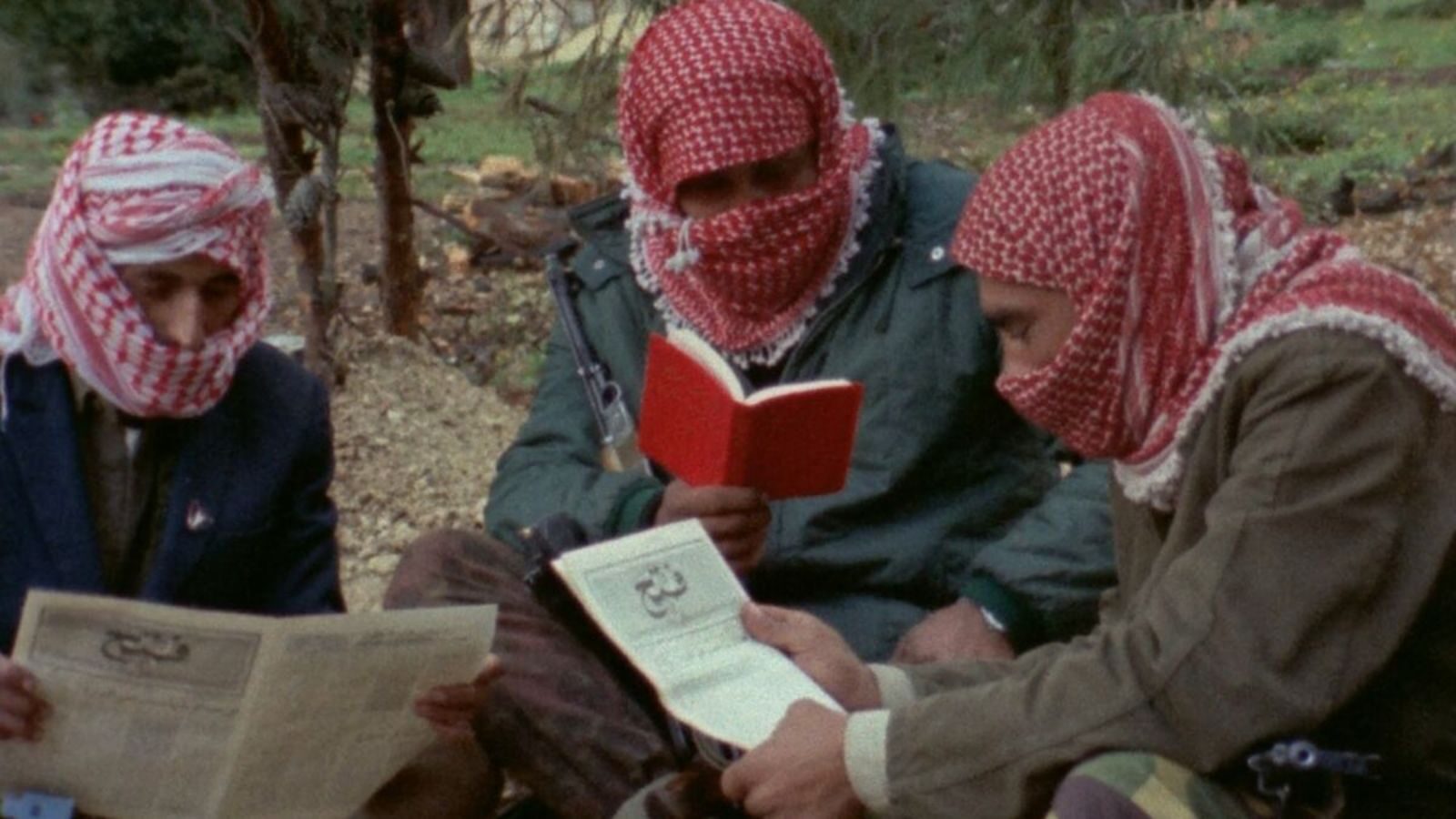

NE: He writes, “To repair is to return the images and the sounds to those from whom they were taken.” But yes, it’s inspiring to find those words being used by a white film critic in the 1970s. It makes me think of Daney’s piece on Ousmane Sembène’s Ceddo [1977], in which he refers to white people’s “infinite” ignorance regarding Africa. Daney was always very clear about where he was speaking from. Part of his critical project was to consider the distance between him and the images. Here and Elsewhere is intellectually formative for Daney, because what Godard and his co-director, Anne-Marie Miéville, were doing was not making pro-PLO propaganda, but analyzing how images from elsewhere (especially political images, notably those Godard had brought back from filming the fedayeen in the Middle East) are perceived here (in French living rooms, on television). Daney’s argument about Godard’s work is that he doesn’t take sides, he takes discourse at its word and compares it with other kinds of discourse—the discourse of the fedayeen and the discourse of French TV, for instance. While I agree that’s how Godard operates as a filmmaker, it would be disingenuous to claim he’s not partisan in Here and Elsewhere, which is why I’m particularly proud of our decision to screen that film with Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s short Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s “Accompaniment of a Cinematic Scene” [1972], which starts with a reading of Schoenberg’s letter to Kandinsky about antisemitism. Both films use the juxtaposition of archival images to create historical lineages, and I think juxtaposing them will give viewers a rich perspective on contemporary events.

ML: Were there any films you didn’t know?

NE: All these films have been on my to-see list since I first got the book 25 years ago. But some are not easy to find, particularly if you’re holding out for the big screen. That was another reason to do the series.

Charles Belmont and Marielle Issartel’s Histoires d’A [1974] was a revelation. It’s a documentary about women’s reproductive rights made when abortion was still illegal in France. It was banned by the French government immediately upon release and subsequently seen by tens of thousands of people through a clandestine distribution network. Shortly after it was finally allowed to be shown in the commercial circuit, abortion was legalized in France. Its landmark political significance made me assume it would be a relatively rote piece of militant filmmaking, but it’s truly a work of cinema. Recognizing that—demanding it—is key to Serge Daney’s approach. What makes a film a work of cinema is the mise-en-scène, in keeping with the auteurist Cahiers tradition of André Bazin and the critics who would become the New Wave directors. But what mise-en-scène means to different generations, beyond where you put the camera, is up for grabs. For me, Daney stands out in the way every sentence he writes balances an aesthetic standard for cinema and an ethical standard for the world, to the point that they are indistinguishable. Daney does what he says no one else thought to do: he writes about the form of Histoires d’A, revealing that the way people are filmed is also an essential act of liberation.

ML: Are there any recurring themes in “Never Look Away”?

NE: History is a big one, particularly World War II and its legacy, which continues to have tragic consequences. In Hitler: A Film from Germany [1977], Hans-Jürgen Syberberg tries to trace Nazism back to German Romanticism and provide a totalizing view of German history. Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One [1980] is a more conventional but equally potent film, following an infantry squad from the campaign in North Africa to the liberation of the concentration camps. In Here and Elsewhere and the Straub/Huillet short, cinema is used to identify historical causality. Godard traces a line from the Bolshevik revolution to Nazism to the occupation of Palestine. Straub/Huillet emphasize the relationship between fascism and capitalism. And then there’s Pasolini’s Salò [1975]. It’s striking how many of the films are haunted by European fascism and World War II, but not surprising: World War II ushered in the modern cinema that shaped Serge Daney.

ML: How is the United States reflected through Daney’s writing and the series?

NE: We’re only showing four American films, though the book also has pieces on Hawks’s Rio Lobo [1970] and Spielberg’s Jaws [1975]. There’s this paradox with people like Daney and Godard, who flirted with Maoism and were highly critical of American foreign policy, but remained deeply affected by the classical Hollywood cinema. It was a fixed reference they kept returning to throughout their lives, reading it differently over time, but never letting it go. In his piece about Samuel Fuller, an American director adulated by some European leftists despite his unabashed anti-communism, Daney refers to Fuller as “ultra-American” in the way he can’t resist “turning everything into stories.” That names a compulsion for stories I certainly share, despite my contempt for the use of “storytelling” in corporate culture. There isn’t much I like better than giving into a rare moment of transcendence at the intersection of art and industry—when the name above the title is Lubitsch or Hitchcock. On the opposite end of the American spectrum, Robert Kramer and John Douglas’s Milestones [1975] is an independent film that takes stock of a generation of American radicals and drop-outs in the aftermath of the 1960s. Daney could relate to these young Americans more than those in Jaws. In fact, Daney said Milestones had more to say to him about his own social environment than any French film of the era. Daney is acknowledging the cross-continental nature of the youth movements of the 1960s and the disaffection that followed, but perhaps also recognizing that Hollywood had turned American experience into a global shorthand. Which brings us to Lightning over Water [1980], the film Wim Wenders made with Nicholas Ray in the final months of Ray’s life. Daney’s surprisingly emotional piece about Lightning over Water is really an essay about a generation of Hollywood filmmakers like Ray and Fuller who became outcasts of the studio system in the early ’60s. It’s an important essay in that it introduces the notion of the “ciné-fils,” which translates as “cine-son” but is a homonym for the French “cinéphile.” Daney is including a hidden autobiographical element here, since he never knew his father, but also positioning himself in film history. It’s as if cinema, and particularly American cinema, were the place to find a father. Or at least, in young Wenders giving old Ray a chance to make a last film, a way to honor history.

We’re showing Lightning over Water with Ray’s The Lusty Men [1952], which is not in the book. There’s a long excerpt from The Lusty Men in Lightning over Water, so it was a no-brainer to use this gorgeous, lived-in movie about itinerant rodeo riders to recognize the importance of classical Hollywood film in French cinephilia.

ML: Daney seemed exceptionally skilled at analyzing films as well as considering the industry machinery that supports or hinders filmmakers.

NE: He’s especially good with that in the piece “The Raw and The Cooked,” which assesses the state of French cinema at the end of the ’70s. Daney writes that the auteurs who flourished and were able to experiment in that decade were those who created microsystems by running their own production companies—Truffaut, Vecchiali, Rohmer, Godard—and those who operated in such a marginal space that their films cost close to nothing—Garrel, Luc Moullet, and Duras. Those who couldn’t create their own machine, as he put it, were less prolific and often frustrated: Jean Eustache, Maurice Pialat, Jacques Rivette, Alain Resnais.

Part of what makes Daney a great critic is that while sometimes you could argue that he’s finding things in films that no one including their makers have seen, he never considers a film outside of its context. That’s especially true when he’s writing about activist films like Histoires d’A and Nationality: Immigrant [1976], where he holds the films to his standards of cinema, beyond their “militant usefulness,” and thinks about how the conditions in which they are made and exhibited participate in the experience of watching them. Daney always considers the film on multiple levels, which is quite different from an American tradition of film criticism that consists of writing a finely wrought, opinionated plot summary.

ML: Was it always clear that Daney had a radically different approach to writing about cinema?

NE: Perhaps the most singular thing about him as a film writer is the trajectory I see him following from this first book, Footlights, in which he’s saying “we,” speaking for the small group of people in the Cahiers orbit, to his last books, in which he’s saying “I,” which is very unusual in the tradition of French criticism. But even in Footlights, in which he compiled and contextualized some of his Cahiers articles to bear witness to and make sense of a collective experience over the course of a decade, that urge to involve himself directly is there. I think that’s what made him so accessible to me. He was an extraordinarily intelligent man, and I can’t always keep up with him, but his way of threading his life into larger history and the cinema—eventually using his life as a measuring stick for cinema—always allows me in. I should also mention that Daney was an unusual person in the Cahiers world in that he was one of the few who had absolutely no interest in making films. He shot one short film in 1967 and said it was a miserable experience. Writing about cinema was not an apprenticeship or second best for him, it was really what he wanted to be doing.

ML: Was Daney queer?

NE: The word he used was “homosexual.” He talked about it publicly at the end of his life, when he was sick, in interviews he gave to understand his legacy. He died of AIDS at 48, in 1992. I hope his gayness will come through in the discussions we’ll host around the series, but in Footlights, you have to read between the lines to find it. Daney considers Jaws very repressive in its treatment of sexuality, for example—the kids who go have sex in the ocean are punished by being torn apart by a shark. There's something about Daney—whether you attribute it to his being gay, or his working-class background—that made him naturally treat people, and films, as equals. I’m tempted to say that Daney’s homosexuality plays into his egalitarianism. He was comfortable being himself, marginal in his sexual identity, modest economic means, and commitment to obscure cultural artifacts. Perhaps that allowed him to engage openly with the varieties of seeing and thinking that are on display in these films.

ML: How did AIDS inform Daney’s seeing and thinking at the end of his life?

NE: Because he was given a death sentence at a relatively young age and had the time to see his death coming, he worked his illness into his understanding of modern cinema (i.e. the cinema of the post-war period, which basically starts with Rossellini), which he saw as being almost in direct parallel to his own life. A crucial moment of self-understanding for Daney came in high school when he was shown Night and Fog, Resnais’ short film about the concentration camps. He already loved movies, but Night and Fog gave him a different understanding of what cinema could and should do. And it was through cinema that he learned about the concentration camps. Those two things are inextricable for him, which is probably why morality is such an important part of his thinking about film. Once he was ill, Daney came to think that the piles of bodies he had seen in Night and Fog represented both his past and his future. He didn’t know it when he first saw the film, but his father was Jewish and most likely died in the camps. Daney came to view the corpses in that film as a representation of his father, and of his own future, as a man turned into a living skeleton by AIDS. It’s grim, I admit, but a potent illustration of how Daney used cinema to think about history and himself.

“Never Look Away: Serge Daney’s Radical 1970s” runs January 26–February 4 at Film at Lincoln Center.