I'm not sure one can say they enjoy a Catherine Breillat film. But that does not mean she isn't one of our most talented filmmakers. Her fairy tales, as well as her explorations of degradation and masochism, rank among the most disturbing and fascinating films of the past few decades—they’re body horror without any fantasy to distract us. Her work is vile, vicious, transgressive, and in bad taste, but in an entirely different way from that of John Waters’s comedies. “To me cinema is unhinged, it’s crazy the way an ax murderer is crazy,” Breillat said at a recent Q&A following a screening of Fat Girl (2001) at Film at Lincoln Center, which recently ran a complete retrospective of her work titled “Carnal Knowledge.”

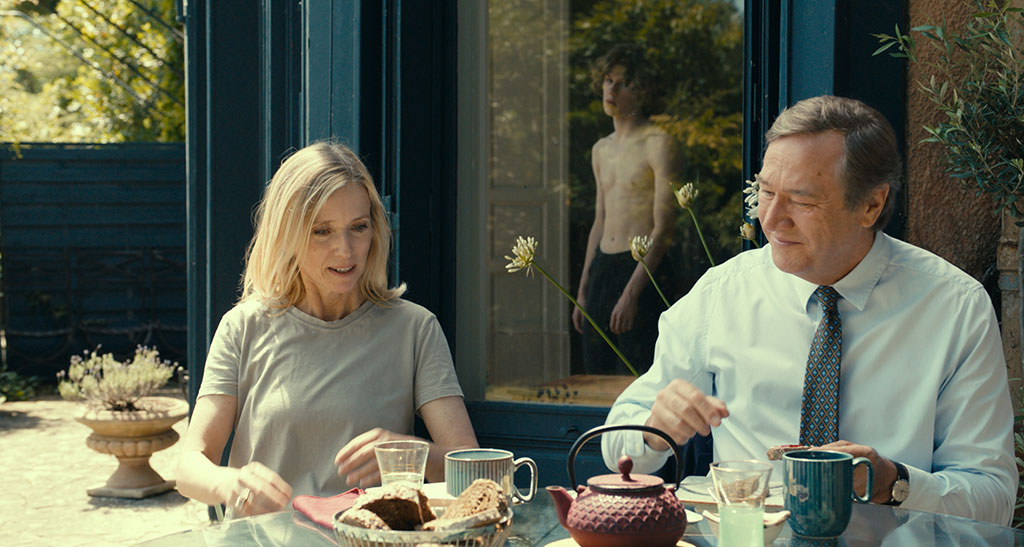

Her films are often about women and feature statements such as “beauty feeds on degradation” (Romance, 1999) and “the woman calls out for mutilation” (Anatomy of Hell, 2004). In her new film, Last Summer (2023), a woman starts an affair with her step-son. She navigates consent and child abuse charges at her day job, but at home she is constantly drinking wine and eyeing her new ward. They are not related by blood but he is 17. His boyish smile belies innocence, even as he slowly seduces her and she falls into his embrace. Both actors deliver powerhouse performances, sinking to new lows with cringe-worthy scenes of flirtation. Watching them is painful.

There are many scenes where Anna (Léa Drucker) is nearly sociopathic in her behavior toward Theo (Samuel Kircher), even more than Natalie Portman or Julianne Moore in the other recently released age-gap drama May December (2023). Afterall, Last Summer is French. The film’s naturalism is even more abrasive than a book like Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s My Heavenly Favorite (2024), another recent work about a predator that has stirred up controversy. Breillat flips the script, challenging our assumptions about gender and monstrosity. Anna struggles to maintain the façade of the daily and remain normcore, in spite of her hatred toward the boring type of people her husband works with. The family is a black hole, sucking in and repressing, as well as destroying trust. It’s difficult not to read this film as one about consent and morality given Breillat’s past comments about #MeToo, Asia Argento, and Harvey Weinstein. Last Summer is a heavy and fascinating work by one of our most powerful contemporary cinematic voices. Breillat and I recently spoke over Zoom about color theory, star signs, filming rape scenes, morality, and working with child actresses. Assia Turquier-Zauberman assisted in translating this conversation.

Grace Byron: How did you start working with Kim Gordon on the soundtrack for Last Summer?

Catherine Breillat: The collaboration started quite late. The film was already over, I was looking for music and I found a book on my work that was edited by Douglas Keesey with Manchester University. When I found this book I contacted the editors. They told me that Kim Gordon, who was asked the same question that the little girls are asked in Last Summer—“What book would you take with you to a desert island?”—answered that it would be this book, on my work. Hearing that—because I was a fan of her work too—I thought that we could find a way to get in contact with her and ask her to make music for the film.

She agreed and came to Paris. At first, it was a bit of a difficult process because she hadn't done this kind of music before. She hadn't made music for film and I was looking for an infra-bass that wouldn't always be audible, but would always be there. It took us some time to work out what that meant, but eventually she sent me a lot of things that I wanted to do and that she was already doing on her own album. It was really wonderful. I got everything I was expecting from it. And, I think there's this way in which one's work can create a genealogy between oneself and somebody else through the ways in which the works speak to us of each other. Her music has already spoken to her, spoken of me to her, spoken to me of her for a long time, and vice versa. That way, when we met we were already on the same wavelength.

GB: How does the idea of innocence play a role in your films? In previous interviews, you’ve said that you don’t consider the dynamic of the characters in Last Summer abusive.

CB: All of my characters are innocent, or else I wouldn't film them. I'm filming them so as to make them be loved and be received without judgment, especially Léa Drucker’s character in this case. I knew that I'd started to succeed in doing this when I was shooting a scene where Samuel Kircher is next to Léa Drucker and my assistant said, “One wishes to be in her place.” From that moment, I knew that I was on the right track of opening up to not the sort of conception of what this dynamic should be—literally innocence—but what is actually there in their dynamic, where there's nothing. There’s no anomaly in it: it is innocent on both sides and graceful on both sides.

GB: Your films always have such specific color palettes. This one is full of whites and spring greens. Can you talk about the role of color in your films?

CB: In Fat Girl [2001] everything is a kind of pistachio green—it was a counterpoint for how to elaborate the color scheme. The scheme in Romance was reds, blacks, and whites. I think you always have to shift from one film to another, and to make each film different or against the previous one. I think it’s a little bit like in painting; painters have a blue or pink period, but still sign with something that is in their authorship. I think it’s the same in cinema.

GB: Similarly, I think a lot about the water in your films. The end of Anatomy of Hell, the seaside town of Biarritz that appears in many of your films, or the scene in Last Summer where Anne and Theo first touch in the river…

CB: I'm a Cancer. [Laughs] During the ten years when I didn't do anything, people would ask me what I spent my time on. I would say that I just spent ten years contemplating water. I have a loft in Paris over the Canal Saint-Martin and well, that's a body of water. But the house where I'm supposed to be spending most of my time is on the island of Brae. I can also see the water from there. The ocean is the most important body of water to me. It fascinates me and scares me. Of course, whatever brings me both the vertigo of fascination and fear is an interesting part of me and of my cinema.

For example, Fat Girl was all written for Taormina, in Sicily, and the scene where they’re walking through the devastated forest was supposed to be on the Etna, which is why there’s an Italian seductor in the film. The issue was that we were working with an Italian co-producer, which was basically the mafia, and we realized that they were going to squeeze more and more money out of us that we didn’t have. It was just starting to be impossible.

At the last moment, I decided to replace Toarmina with La Palmyre in France. I had a friend who had a house there who was dating a very famous football player. Thanks to him, we got all of the authorizations on time and we were able to recreate everything without changing a single date of shooting even though we had just rearranged the entire production. This way, the storm that had devastated the forest became the replacement for the volcano. It was just as good and the storm was welcome, as are any obstructions that occur, which in my opinion are always coming to make things better to a certain degree. Especially, because now that I’m thinking about it, I really don't like the Mediterranean that much. It's too blue to my liking. I like green.

GB: What was working with the cast of Last Summer like?

CB: The film was made in a state of grace that was both rare and absolute. Everything happened in such a way so that when the set was cleared and the film ended we were all orphans of the film.

I don't talk to the actors during the film. I only talk to them during the scenes when I'm directing them. I have no time. I only become friends with them after the film, which was the case with Léa, whose intelligence I only discovered after the shooting ended. I didn't understand why she was putting up with me because she tends to be a neighborly person, or at least that’s how she is portrayed in French cinema. I didn't understand why she was putting up with my way of directing. She was saying, “No, no, I love your work. You're a great director.” And I was like, “Really, you're sure? You know, the French general public hated me so much.” And I didn't put in any work to try and seduce her.

I was going in very hard. She said that I broke all of her tools of acting, because the truth is, I don't like the way that French actors act. They act and I'm trying to get them to be. To break that one needs a certain kind of violence that I exert and then worry about later. But I heard from the people who worked on the costumes that whenever my actors would return after the day of work they would be radiating with joy and that they’d be saying, “Catherine is so hard,” but also really enjoying that process because they're artists, the same way that dancers are dancers, or alpinists are alpinists. It's hard to get to that place where everything is easy and it requires a great level of self-abnegation to do so.

When Samuel first came to the audition he was talking. He wasn't acting. He was just saying what was there. But, he had something that I was able to work with and he was fantastic. Léa thought that I had purposefully given her a scene partner who was 17 and not 18 in a spiteful way, because we were originally trying to get somebody who was not a minor. But that wasn't the case. In the end, everybody got along very well. And Léa knows Samuel’s mother. At first she thought it was going to be very awkward, but everything went fine.

GB: You work with children a lot in your films. The scene of Isabelle Huppert auditioning kids in Abuse of Weakness really stood out to me.

CB: I love to work with children because, like I was saying, with adults, I have to be very hard to get what I want out of them. But that doesn't work with children. They wouldn't be right. Children have to love you, to listen. There's no point in giving them orders, they're not going to obey. The dynamics of that are so different and so wonderful because you just have to give them back the love they give you in a way that is generative. And they are so surprising. There’s no calculation in their way of being in front of the camera—a generosity that I really marvel at.

I especially think of the girl in Bluebeard [2009] that I loved so much. It was really shattering for me when the film ended because of how much I loved her. It was really something that took a toll on me. There’s this scene when she's coming down the stairs in her nightgown and she's reading—everything was so cold around her. She was so scared despite having been shown how all of the hung bodies were special effects; we were really trying to make all of that very clear to her. But of course, she was still scared, and she was walking on this cold puddle, that was so slippery, with this book. She just kept on mumbling to herself, “I'm not scared. I'm not scared. I'm not scared.” And there's something about the courage and the tenacity of that that I found admirable.

GB: You’ve talked in the press a lot about some of the key scenes in this film—about consent and morality. How did you approach making a film about such a charged topic as that of a mother having an affair with her stepson, especially in such a naturalistic way?

CB: My aim is to make people lose a sense of the certitude regarding the compass of good and evil as dogma, which scares me and resembles a kind of fascistic interpretation grid. As a humanist and not a moralist, I’m trying to engage with it to the degree that I’m refusing to abide by the compass of good and evil in my art.

GB: You’ve talked before about MeToo in the press. I’m wondering how that plays into this context.

CB: I’m scared, not of the MeToo movement proper, but of people in the cultural landscape after MeToo, especially of a kind of radical feminist imposition on the world of cinema. This is a more dangerous second McCarthyism that could police and regiment what can and cannot be done on a film set in a way that will eventually create the same problems again. Intimacy coordinators will soon be revealed to abuse their own power. There’s a play in France called Tartuffe that speaks exactly about this, to the hypocrisy of those who are trying to set the moral framework for everybody else.

The issue is that all of the abuse—that has very, very rightfully been called out—tends to occur outside of the set. But on set, there's at least eight people present for any one sex scene. And this is not when the surveillance is going to actually make a difference. When somebody like Jean-Luc Godard asks an actress to get naked while reading the Bible or the phone book as she walks around a table—there's something perverse about that and no intimacy coordinator can be present then. So, I really have an issue with self-proclaimed surveillance teams coming to patrol my sets when there's no science for that. It’s a completely self-appointed job, which I think in the end will breed more of the issues that it's supposed to counter.

The issue with intimacy coordinators is that they impose their own morals on actors who are artists, and who have their own artistic relationship to the director. A sex scene, if it is to exist in a film, is necessary; and, if it is necessary, it can be done by the director. The director is the one, who in this artistic relationship, is supposed to bring the actor to the place of the sublime that such a scene needs to have in order to be justified in the film. If one isn’t able to do that, then one shouldn’t have that scene in the film. To get to that place is to get to the same place as having sex with somebody you love, because being in love is done in the same way. It’s about being able to carry out trivial things to get somewhere that is beyond the trivial and that no intimacy coordinator can assist anybody with.

It’s a really, really important thing that people have shed a light on abuses that have gone unpunished. But that doesn’t mean that we should be anticipating this abuse and suspecting it in all places, especially with the directors when the intimacy coordinators could just as well be abusing their own position of power. With Last Tango in Paris [1973]—which I worked on for two weeks—there’s the same questions about the ways in which a moral reading is applied to the last scene. A rape scene is not a rape, it’s a scene. I’ve done rape scenes and I’ve been asked whether there was violence at hand. There’s the importance of fiction.

What Maria Schneider did have to go through and was very perturbed by—outside of her own life and her own family history—is something about her father, who was a very famous French actor who did not recognize her. Throughout her life, the world made that a relationship so that every time she would go to a restaurant, somebody would put that on her table without her asking for it. There was some kind inspiration there related to the film, but it wasn't Bertolucci proper. The only thing that she ever blamed him for was for not having given her more than the $17,000 that they had originally planned for the film despite the fact that the film was a huge success. That she was very, very unhappy—which is undeniable—has more to do with the general population’s gaze toward her and what it means to be skyrocketed to that kind of visibility, and to be a sex symbol. In a way, all sex symbols are miserable for being in the gaze like this. This is different from the responsibility of the actual director and I find that we must maintain our capacity to not confuse these things.

It’s very important for people to know the difference between the conditions that lead, for example, to Maria Schneider's death—a large part of which is her fraught relationship with her father, like Alain Delon’s biological son who was also found dead in the same conditions for the same reasons. But there's other factors that we can think about in terms of what leads to such disarray. Alain Delon’s biological son did not film Last Tango in Paris. It was not Bertolucci’s fault. That doesn't mean that we should forever bar the possibility of making a scene like that. To me, that seems like a fallacious way of thinking pushed by a radical ideology whose only intention is to control the filmmakers who are getting in the way, which is to say, those who are making good films.