CONTOURS is a new column by Saffron Maeve examining films that thematize the world of visual art: heists, biopics, documentaries, and experimental fare. Maeve also programs a screening series of the same name and premise at Paradise Theatre in Toronto.

Over the course of six weeks at the Brooklyn Museum, two dozen local middle school students are encouraged to engage intuitively with the Egyptian collection in order to create a piece of theater that encapsulates their growing connection to the sculptural objects. The world of this museum is elastic; students devise a movement piece, gesticulating, leaping, falling, bowing, slumping, standing still. Shot on 16mm, Stan Lathan’s Statues Hardly Ever Smile (1971) observes this process of immersion, featuring a remarkable assemblage of Black art workers: Kathleen Collins edited the film, Kent Garrett produced, St. Clair Bourne and Leroy Lucas photographed it.

Exhibitions often lean on an aseptic mode of viewership for preservation’s sake: look but don’t touch, feel but don’t feel. In Statues Hardly Ever Smile, contact is encouraged, though certain objects remain cordoned off behind glass. The children graze what looks to be a diorite bust, cupping its stony cheeks and tracing the contours of its chin; four of them then assume the gestures of a nearby figurine. Few films manage to honor the haptic and corporeal experience of taking in visual art, as Lathan does here; most privilege onscreen art as an extension of psychogenic characterization rather than bodily memory.

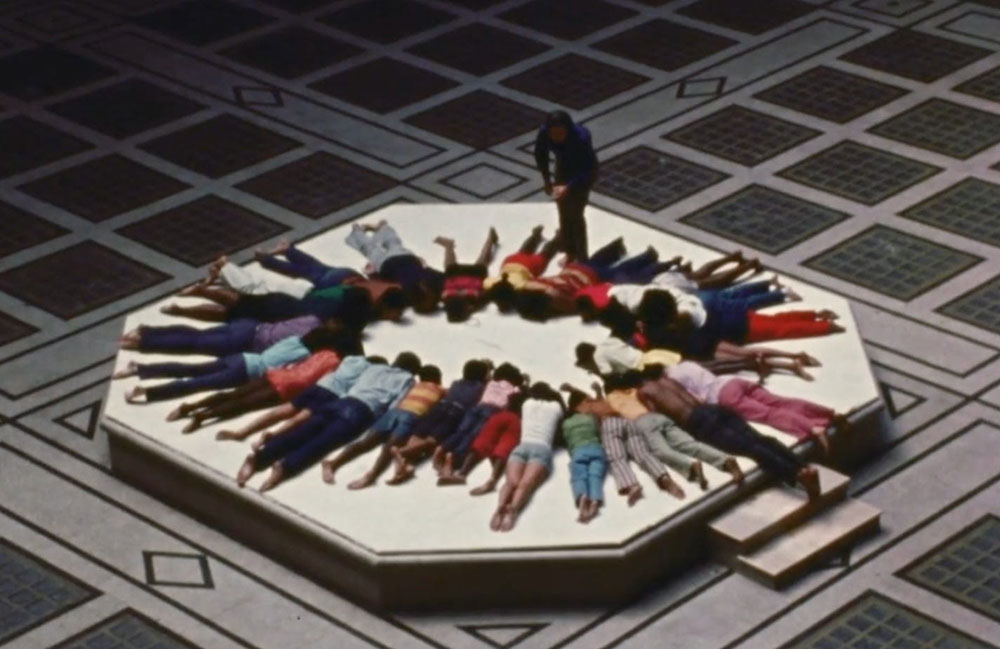

The camera first pans around a rotunda, finding curves and imposing archways, curtained off with flecks of light peeking through. The children occupy the room with confidence and familiarity, following an instructor’s acting prompts: they mime bearing and releasing a heavy weight, then lifting an expanding balloon. Their movements are at once restrained and liquid, as if mimicking the contained yet expressive mien of the sculptures on display. Voiceover by a member of the museum’s education department tells us that the rotunda where they hone their performance skills began to feel as though it belonged to these students and nobody else.

“The whole body moves, remember that,” the instructor preaches. “There is no such thing as one part of the body moving.” The students lay splayed out on the floor, their bodies coagulating into a nondescript figure. Later, they assume a similar position amid the exhibit, where they take turns sharing their opinions on the surrounding art. The film’s emphasis on art as a pellucid and collective effort may lean cultish—children chanting in a perfect circle and assuming the posture of religious statues—but this disciplined ritual yokes together the youth of 1970s Brooklyn and ancient Egyptian portraiture, analogizing through sound and gesture what paint strokes and chiseled stone cannot.

Statues Hardly Ever Smile screens tonight at the Museum of the City of New York alongside Martin Scorsese’s Italianamerican (1974) and Gary Weis’s 80 Blocks from Tiffany’s (1979) in the 1970s edition of the series “New York on Film: Decade by Decade.” The screening will be introduced by Melissa Lyde, the founder of Alfreda’s Cinema.